by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Coffee House Press, Semiotext(e), 2014, 2012 | 272 ; 312 pages

The history of women writers is a history of journals whisked under the table, of poetry reshuffled behind letters, of diaries burned prophylactically by unnerved husbands. Jane Austen famously asked that the creaky door to her drawing room not be fixed so she could hear if someone was coming in, and wrote on small pieces of paper that could be easily hidden in a box. The Brontë sisters hid their successes from their brother because they didn’t want to intimidate him. George Sand not only hid behind a masculine pen name, but concealed herself under men’s clothes so she could go to cafés. Emily Dickinson hid in her house in Amherst, Djuna Barnes in her apartment at Patchin Place. Zelda Fitzgerald, deemed mad, was herself hidden away: she lived out the rest of her life in an asylum and died there in a fire, with nothing to identify her but one charred slipper.

Today we insist the female writer enjoys better prospects in publishing, yet this history of concealment rehaunts in the form of self-censorship and self-effacement. A teacher recently told me that only her female students have difficulties when she prohibits the use of qualifiers such as “I think,” “maybe,” and “I don’t know if…” Or consider the “uptalk” we associate with young women, which is generally associated with indecisiveness and insecurity. Simone de Beauvoir writes in The Second Sex: “As Virginia Woolf has made us see, Jane Austen, the Brontë Sisters, George Eliot, have had to expend so much energy negatively in order to free themselves from outward restraints that they arrive somewhat out of breath at the stage from which masculine writers of great scope take their departure.” Indeed, for women, to write powerfully and affirmatively is to work against a cultural gravity.

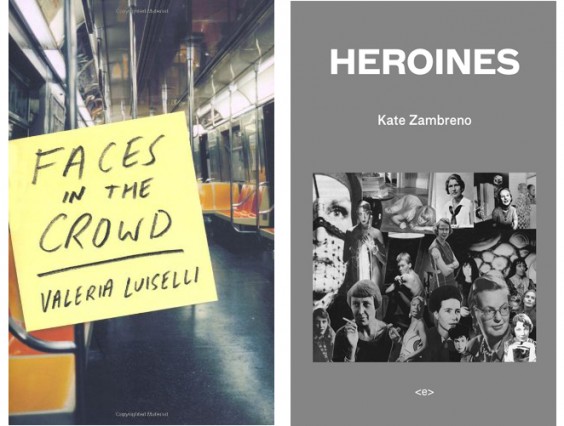

So it is perhaps unsurprising that two recent books by young women writers—Valeria Luiselli’s debut novel Faces in the Crowd and Kate Zambreno’s Heroines—both have at their centers an invisible, self-effacing, ghost-like female writer.

Valeria Luiselli’s debut— translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney—is a book whose ingenious formal structure preserves this strenuous negotiation between the contrary impulses to expose and hide away. The unnamed novelist-narrator has two children and a husband, and they live in a small, unremarkable apartment in Mexico City. The novelist-narrator’s goal is to write a novel in that genre traditionally associated so powerfully with the masculine—the bildungsroman. The set-pieces are predictable: New York City, a lonely protagonist, identity troubles, a story of “another city in another life,” early twenties, precarious employment in a publishing house that resurrects “foreign gems.” The narrator is only able to offer these few small details before she wavers. “Novels need a sustained breath…I am short of breath.” With two children, she can only write in short bursts. In a chilling echo of Plath, the narrator says she must be “silent…so as not to wake the children.” As a result, each section is only a few lines long, and the narrative jumps back and forth between past and present, small asterisks indicating the shifts.

Within the novelist-narrator’s novel, the novel-narrator, while doing research in the library, stumbles upon the letters of Gilberto Owen, an obscure Mexican poet who lived in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance. Initially, what rouses her attention is simply his address: 63 Morningside Avenue. She realizes that they are neighbors, in a sense, albeit living at different times. She climbs to Owen’s roof, chain-smoking and reading his letters and poems, waiting for some kind of “signal.” Spoting a dead potted plant in a corner that resembles one that Owen has described, she takes the dead tree and heads to the door, only to find it locked from the inside. Afraid to yell for help, she spends the cold night alone on the roof with Owen’s metaphorical ghost, interpreting the experience through the most unobscure dean of North American letters:

I once read in a book by Saul Bellow that the difference between being alive and being dead is just a matter of viewpoint: the living look from the center outwards, the dead from the periphery into some sort of center. Perhaps I froze, perhaps I died of hypothermia. In any case, it was the first night I had to spend with Gilberto Owen’s ghost. If I believed in turning points, which I don’t, I’d say that I began that night to live as if inhabited by another possible life that wasn’t mine, but one which, simply by the use of imagination, I could give myself up completely.After the rooftop incident, the narrator is determined to find a place in the literary canon for Owen/herself. That she attempts to do so through an elaborate plot of impersonation gives the work a considerable feminist coloration.

It is relevant to note that Victorian mediums were almost always women. This is most likely because it was believed that women had weaker wills that could be controlled more easily. But if to read and write is also to invoke the dead and enter freely into other consciousnesses, then this is a willed haunting, a concerted effort to live “as if.” Reader and writer are actively fused in this moment of mutual haunting. The incidental parallels between the novel-narrator and Owen—same nationality, same neighborhood, same dead plant... these alone suffice for the signal she seeks: go ahead, follow in my footsteps, adopt my plant, become a writer.

Our novel-narrator ultimately gains recognition, but only by hiding behind Owen and other more famous, white, heteronormative men: a poet named Josh Zvorsky and her editor named, simply, “White.” She remains eclipsed by men even as she begins to write her own, authentic novel, censored, for example, by her husband, who takes offense to passages about her masturbating and her relationships with other men. She even splits her manuscript into two different novels to divert him and satisfy his curiosity. As the text splinters formally, the reader loses the ability to distinguish between the novelist-narrator’s “real” novel and the novel-narrator’s “fictional” novel.

Haunted – or hounded, more accurately – by history, by the great modernist literary men, by her own scrutinizing husband, the young female narrator proposes to write “a horizontal novel, told vertically.” Instead of moving diachronically through time, her story is constructed in storeys, as though the past were living upstairs, stomping around in heavy boots, and the present a quiet tenant downstairs, listening and recording. By writing a vertical novel, she can inhabit any time, any subjectivity, regardless of whether patrilinear “history” has permitted her entry. She can even become Owen himself. Traces show through the membrane of folded time—as when Owen catches a glimpse of her in the subway. She is Owen looking at herself, a contemporary and equal. Her “storied” novel of simultaneous subjectivities, then, becomes a way to infiltrate an exclusionary literary myth and also to inhabit what Kristeva calls “women’s time”—cyclical, maternal, timeless.

*

Published in 2012 by Semiotext(e), Kate Zambreno’s Heroines, a work of literary scholarship, offers a revisionist history of the mad wives of modernism, to whom she refers as her “invisible committee” of “ghostly tutors.” Even to those versed in feminist literary biography, the litany of injustices recounted here will be long and shocking. I read on in amazement about how Scott Fitzgerald stole Zelda’s journals and used them for his own novels, often quoting her material verbatim; how T.S. Eliot knowingly published the gossipy caricatures of the despised writer “Fanny Marlow,” then outed Vivienne Eliot as the author (the final act that led to her unraveling); how Joyce’s daughter Lucia, muse and collaborator of Finnegan’s Wake, was institutionalized for throwing a chair. In Zambreno’s retelling, a pattern emerges in that these women were all artists who were cruelly suppressed. Silenced, their desire for expression subsequently turned inward and catalyzed their self-destruction. These women are all the “thwarted Mary Carmichaels” of our literary history.

Zambreno’s own coming-of-age, as recounted here, begins unencouragingly, with a move to Ohio for her husband’s job. With few friends and zero prospects, she spends most of her time at home writing and researching, “a woman trapped inside her home, haunted by the mad wives of modernism.” Like Luiselli’s narrator, she gets a start by putting on the character of the writer, pantomiming. She begins to dress like a modernist, wearing cloche hats, and she cuts her hair short. Zambreno, too, invites hauntings. When she bleeds all over her sheets she is Vivien(ne) Eliot; when she has a headache she is Simone Weil, Sylvia Plath.

And yet there are differences between the novels as well. Where Luiselli’s narrator performs discretion to its uttermost limits, Zambreno’s posture is one of accusation and defiance. She has learned the lessons from her tutors and refuses to disappear or censor herself. Her messy menstrual periods, her irritable bowels, her thinning hair, her white hairy legs, her habit of reading with her hands in her pants are all limned painstakingly. She writes against invisibility:

When I don’t write I don’t feel I deserve the day. I stay inside and choose not to exist. I mimic one of my favorite living authors, the acidic Austrian novelist Elfriede Jelinek, at home in her designer clothes, always, always at home. Yet isn’t the Great White Male Writer also under a self-imposed house arrest while creating? Who gets to say what’s pathological?By seizing the writer’s duty Zambreno hopes to seize male privilege. As a writer, she can “choose” not to exist, confined to the house by her own will. Simone de Beauvoir would argue that men are subjects and can choose to act, whereas women remain objects and are acted upon; only a wife is “confined”; a husband is “working.” But for all her defiance she makes no attempts to conceal her simultaneous shame; a house-bound writer who can’t write is, after all, “just a wife.”

In Faces in the Crowd as in Heroines, to speak is to be ridiculed—Zambrero was called a “menstrual blogger” by the writer Jimmy Chen on the experimental literature blog HtmlGiant—but to keep quiet is to disappear. Like many of the ghostly tutors in Heroines, the narrator at the end of Faces in the Crowd does finally manage to finish her vertical novel, but at a devastating cost. As Joan Didion so deftly put it, there is a fundamental wrenching contradiction to being a woman and a writer. Because writing is a willful transgression that exposes and courts humiliation, those who engage in it are often “left to wander about in their dreadful freedom like old oxen left behind.” While the men are free to go, the men who work loudly at their desks, their voices booming from across the room, the women artists must still sing with their heads deep in a bucket so as not to disturb the neighbors.

Anelise Chen is a writer and teacher currently living in New York City. Her essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, The Rumpus, The Morning News, The Margins, and other places. You can follow her @anelise_chen.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig