by by Margaret Kolb

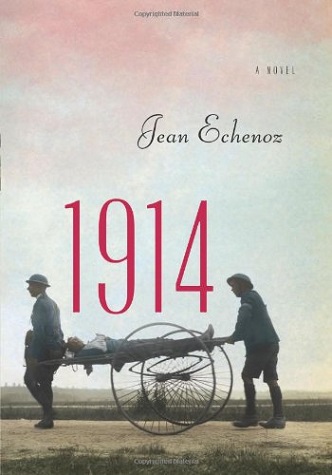

Published by The New Press, 2014 | 109 pages

Richard Overy, a leading World War II historian at University of Exeter, began his 1995 book Why the Allies Won with a question as provocative as it was perceptive: did we win? Of course the Allies defeated Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in the military conflict that ended in 1945. But if we generalize the concept of “victory”, the answer becomes much less certain. Britain lost her empire and her preeminent international standing; Stalin consolidated his power in a Soviet Union that, until then, had been steadily declining; the U.S. was thrust into the “quagmire” (to quote Donald Rumsfeld) of global law enforcer. Meanwhile, (West) Germany and Japan embraced pacifism and embarked on unified and peaceful journeys towards social progress and broad-based economic advancement. Overy’s perceptive question raises intangible epistemological threads that traditional histories of war generally avoid. Some of our deepest analysis of this opaque terrain has, instead, come from our poets, artists, and theorists.

Jean Echenoz’s recent novella, 1914, takes us back to the front lines of the First World War. The plot follows five young French men through the initial naïve excitement of “mobilization” and their subsequent introduction to modern warfare. They are all ultimately killed or wounded, each one in a distinct and profoundly emblematic scenario. In a parallel narrative, Blanché, fiancé to one of the killed Soldiers, is left to raise a son with nothing but a photograph for a father. As the novel ends, she conceives another son with the brother of her killed fiancé, and the cycle of delusion and violence drives relentlessly towards its reenactment in the Second World War.

The Great War is too often considered only in relation to the rise of Fascism, Soviet Communism, and WWII. In truth, the technological and tactical advances it ushered forth make it arguably the most dramatic turning point in the history of warfare. In the first battles on Belgian and French soil, nineteenth century tactics collided with twentieth century technology in absurdly horrific fashion. Cavalry charges, the most powerful force in maneuver warfare from Roman times to the turn of the 20th century, were massacred in seconds by single machine gun nests. Massed infantry formations, the backbone of warfare since the Bronze Age, were easy targets for long-range artillery fired from up to 30 kilometers away. Military commanders eventually did adapt, digging trenches and constructing interlocking defense in depth systems, prompting aggressive maneuver advancements in response, and ultimately creating the modern battlefield. The machine gun, accurate long range artillery, aviation, motorized transportation and the railroad are just a few of the technological advancements that, in 1914, revolutionized the conduct and consequences of armed conflict, and the broader geo-political landscape.

The technological leaps in the First World War were revolutionary, but every advance in the history of military technology has been in pursuit of, or in response to, one fundamental concept: increasing the range, accuracy, and destructiveness of ballistic (projectile) weapons. The tactical benefit of such advancement is obvious, but the broader set of epistemological consequences less so. Killing becomes mechanized and the enemy abstract, anesthetizing the Soldier to the act of taking life. Furthermore, there is no courage or honor when death is arbitrary and cheap; those emotions, once central to the experience of war, are replaced by feelings of futility and despair. It is this process that is explored in 1914.

Echenoz’s principle means of transcending this tactical and technological complex to (re)engage the human is through scenes of vivid death and suffering. Charles is the first victim in the novel. Though transferred at the outset of the novel from the Infantry to the nascent Air Corps because his family has connections in the government and believed that would be safer, he is later killed, in a deliberately exaggerated scene, when sitting as a passenger taking reconnaissance photographs in an early warplane (no functioning weapon, no training on aerial combat maneuvers, no redundant controls). His pilot is shot through the eye by a single rifle shot from a similarly crude pursuing German biplane. This scene captures the amateurism and naïvity with which European nations approached international politics and conflict in the build-up to the First World War. With the benefit of hindsight, we marvel at the innocence, and even excitement, of these first combat pilots. Charles’s clumsy and haphazard death metaphorically initiates the race to weaponize the sky, which today is our most active battlefield. These first daring pilots could have never imagined a sky filled with strategic bombers, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and unmanned drones armed with precision-guided munitions.

Arcenel’s execution at the hands of a firing squad tells a darker story about the tragically perverse nature of military “justice.” Having recently lost his final remaining close friend in his unit, Arcenel is arrested by the rear guard while walking through the countryside during a lull in the fighting and is sentenced to death by a farcical summary courts martial for attempted desertion. It is a heartbreakingly realistic scene. The French were, in the First World War, more apt to summarily convict and execute supposed deserters than their German or Austrian enemy. But regrettable applications of military “justice” are replete throughout the history of organized warfare. The Italians, for example, practiced “decimation” (resurrected and repurposed in the novel World War Z) in which entire units were punished by making the Soldiers draw lots, and then executing the unlucky Soldier who drew the losing straw.

1914, translated by Linda Coverdale, clearly has aspirations beyond that of traditional historical fiction. Echenoz employs an objective and temporally circumscriptive narrator to achieve what the famous German philologist Erich Aurbach referred to in his study of Homer’s Iliad as an “externalized form.” Instead of a traditional third person omniscient perspective, however, 1914 is told from the first person retrospective. The narrator is our contemporary, telling the story like a grandparent recalling distant memories, but without revealing his own position in relation to the specific characters or events. He is therefore able to both be objective – as he combines memory with the wisdom of hindsight – and human, in his treatment of such poignant themes. The effect is to transcend the local – to speak to a broader experience than the text’s specific context or fabula.

Echenoz’s narrative technique is not without its flaws. The first person retrospective narration prompts questions about memory and perspective, but the text, in its brevity, lacks the depth in its historical backgrounding required to make those questions productive. The history of the First World War requires no broad rehearsing, so 1914 must achieve uniqueness through its mode of transmission. However, there is no irony in the narrator’s foreshadowing or the characters’ symbolic anecdotes, and without clear and specific historical context, the metaphors are too general. The reader is left questioning the narrator’s location and purpose instead of exploring the potentiality of the text.

The dominant themes of 1914 – the horror of war and its tragically arbitrary and cyclical nature – have been exhaustively treated. Echenoz’s text strives to transcend those tired motifs and disclose a global truth. However, these broadly accessible themes are familiar enough at this point to be almost comfortable, and Echenoz’s grand gestures are occasionally transparent and lack in real substance. It is a text that straddles the line between art and pulp fiction; it may be too early, at this time, to determine how it will ultimately be judged.

Adam Karr graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 2005 with a B.S. in International History, and in 2014 earned a Masters in English from the University of Virginia. Adam also served a 14 month tour in Baghdad, Iraq and a 13 month tour in Nangahar Province, Afghanistan. He currently instructs English at West Point.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig