by Angela Moran

Published by The MIT Press, 2009 | 400 pages

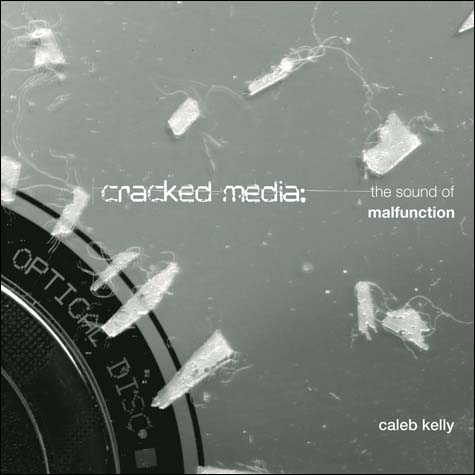

Caleb Kelly's Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction investigates the intersection of music, performance art, and sound studies in the object of media that has been “cracked.” “Cracked media” are, according to Kelly, “the tools of media playback expanded beyond their original function as a simple playback device for prerecorded sound or image. ‘The crack’ is a point of rupture or a place of chance occurrence, where unique events take place that are ripe for exploitation toward new creative possibilities.” Cracked media, then, include damaged or destroyed vinyl LPs, compact discs, altered turntables and CD players, broken tape loops, production of excessive feedback and noise, and so forth. Rather than being unwanted artifacts of wear and tear or user error, these effects are intentionally created and deployed by these artists as an integral part of their aesthetic.

Kelly's analysis brings together a diverse array of thinkers and artists in the United States, England, Japan, and Australia. He focuses mainly on avant-garde practices in music and the visual/performance arts, which he does quite well; the main defect of Cracked Media is that it does not focus on a broader array of artistic practices, especially those within the realm of popular music, that could add further depth and nuance to his narrative and arguments.

The book is divided into four chapters and begun with an introduction. The introduction, as one might imagine, sets out Kelly's problematic and the main contours of his subsequent argument. The first chapter, entitled "Recording and Noise: Approaches to Cracked Media," is primarily theoretical. Kelly draws heavily on the work of Theodor Adorno and Jacques Attali -- the go-to thinkers on noise and mediation within music/sound scholarship. Although it certainly makes sense to draw on these theories, I hoped for some more original theorizing about cracked media from Kelly himself. He certainly has quite a bit of data on cracked media at his fingertips, and he could have used that information to draw conclusions that develop the work of previous thinkers. He does mention that "the use of cracked media in the creation of sound and music problematizes Adorno and Attali's critiques of recording technology. It calls for a reevaluation of the potential for original and creative output from the end point of the recording industry, the point of playback.” However, he only develops this problematization over two short pages. Adorno's work in particular is in need of development: primarily writing on recorded media well before World War II, his work doesn't apply particularly well to the sophisticated uses of contemporary media that Kelly describes here.

The last part of the first chapter explores the concept of "noise." Kelly lays out four primary approaches to defining noise. The first, drawn from audio scientist Herman von Helmholtz, hears noise simply as random sound stimuli, as opposed to the patterned and intentional stimuli of music and speech. The second, drawing from information theory, opposes "noise" (unwanted sound) to "signal" (wanted sound) in communication systems such as telephone lines.

The third hears noise as an entirely subjective phenomenon: the example given is a mother and a teenage son arguing over loud music--to the mother, the music is noise, whereas to the son, his mother's voice is the noise. This definition of noise is, I think, the most pertinent to Kelly's broader argument, and I wish that he would have developed this line of thinking further, to include politicized social definitions of noise. For example, hip-hop has often been perceived as "noise" (as opposed to "music") by those who dislike its political and social positions; this is clearly a subjective response based on social and political beliefs that critics hold toward aspects of black cultural production. (Tricia Rose draws on this in her 1994 history of hip-hop, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Wesleyan University Press).) Even the example Kelly cites could have been unpacked politically, drawing on discourses of intergenerational conflict and the association of loud, "noisy" music with teenage rebellion.

The fourth hearing of "noise" draws on the work of Michael Serres, who posits a constant background of noise as "the ground of our perception"--an almost material presence in the world. Kelly then develops and integrates these perspectives with respect to cracked media, hearing "noise" in these context as, almost-paradoxically, "not-noise," because it has been subjectively re-valued by practitioners and audiences of cracked media.

Chapters two and three are case studies. Chapter two focuses on "the manipulated, modified, and destroyed phonograph," drawing on the work of avant-garde music and visual artists Nam June Paik, Milan Knížák, Christian Marclay, and various artists who have worked with modified and/or destroyed turntables (as opposed to vinyl records themselves). These artists have pursued a variety of practices, from cutting and re-assembling records (Knížák) to installing many records on the floor of an art gallery and selling them after they had been scuffed by people walking over them (Marclay). It was in this chapter that I felt that Kelly missed a crucial opportunity to critically examine contemporary popular music, especially hip-hop. Although hip-hop artists have not often actually broken or destroyed records and/or turntables, they have certainly pushed these media to their limit in developing new creative practices, fomenting a mass re-evaluation of the nature of both "noise" and "music" in the process. Given that this art form has had a worldwide impact--certainly much more so than the work of the artists profiled here, although I don't intend this comment to devalue their work in the slightest--this omission stood out as particularly glaring to me.

The third chapter focuses on similar practices that have been done with compact discs. Because they are digital and CD players are designed to correct for damage to the disc, it is much more difficult to creatively re-purpose CDs and CD players toward explorations in cracked media. In this chapter, Kelly focuses on the work of Yasunao Tone, Nicolas Collins, and Oval in particular.

The concluding chapter, "Tactics, Shadows, and New Media," develops Michel de Certeau's theories of tactics and the everyday with respect to cracked media. Kelly glosses "tactics" as everyday practices that "are there to make life a little better and perhaps a little freer.” Although it is true that practitioners of cracked media use everyday, readily available technologies, and alter them in idiosyncratic ways to meet their own artistic needs, I'm not convinced that this is the best analysis here. First, it takes little account of the experiences of audiences, as opposed simply to artists. A comprehensive theory of cracked media should do both. I am additionally skeptical of the niche, avant-garde, underground nature of most of these artistic practices. Although these artists may be well-known within the artistic community, their work has not had a broad impact on many people's everyday lives. Again, this is not to devalue their work nor Kelly's analysis, but simply to say that his claims about the nature and significance of cracked media are necessarily limited in scope. If Kelly had engaged with popular music forms and a broader range of contemporary theory, he would be on solid ground to make more general statements. To be clear, he doesn't purport to make sweeping statements about broad swaths of cultural experience, but I find his use of "the everyday" incongruous with the limited nature of his case studies.

In short, Cracked Media is an intriguing and well-done, albeit limited, work. If one reads it as the jumping-off point for a broader discussion (rather than a definitive and comprehensive analysis) on cracked media practices and the changing role of noise (and/or "noise") in the realms of music and visual/performance art, it is well worth the time.

Meredith Aska McBride is a Chicago-based ethnomusicologist, writer, violinist/violist, arts administrator, and music teacher. She is a graduate student in ethnomusicology at the University of Chicago and is currently a University of Chicago Urban Doctoral Fellow. Meredith’s research lies at the intersection of ethnomusicology, urban studies, and Jewish studies. Her previous writing has appeared in Philadelphia Weekly, Next American City, and The Daily Pennsylvanian.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig