by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Coffee House Press, 2011 | 186 pages

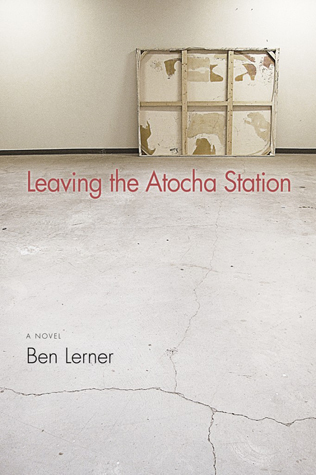

We know all too well what can happen when a person reads too many novels. The Quixote syndrome, where a person suffers for a belief that the world outside is supposed to conform to the uncanny logic of fictional worlds, has been a recurrent trope in fiction since its seventeenth-century debut. But what happens when a person suffers similarly, but for poetry? This is the question Ben Lerner pursues in his first novel Leaving the Atocha Station (2011), an autobiographical portrait of a young poet’s year spent in Madrid evading the responsibilities of his “prestigious fellowship,” smoking a not inconsiderable amount of hash, and mistaking cultural misunderstanding for “negative capability.” Following three notable collections of poetry—The Lichtenberg Figures (2004), Angle of Yaw (2006), and Mean Free Path (2010)— Atocha is Lerner’s first major foray into prose fiction. It is also his attempt to examine what it means to be an American artist of language in the first decade of the twenty-first-century. The March 2004 Al Qaeda commuter train bombings fracture the novel, and protagonist Adam Gordon’s uncomfortable failure to come to terms with the place of the poet in global politics is Atocha’s core crisis. As a highly symbolic, psychological novel by a poet, Atocha has the atmosphere of Sylvia Plath’s frequently underappreciated The Bell Jar. Only there are two differences here: Gordon uses anti-depressants, which keep him from the suicidal depths of Plath’s protagonist, and he more explicitly stresses his interest in the socio-historical world at large.

Atocha begins in medias res in the fall of 2003. By the time we meet Lerner’s innocent abroad, he has already installed himself in a cramped Madrid apartment off the Plaza Santa Ana. He has moreover already established a Spanish routine he might have read about in The Sun Also Rises, albeit with the cannabis consumption. Most days Gordon seems content with his existence as a flâneur in the city; he meanders from his favorite “hard bread and chorizo” café to the Prado to the park El Retiro. Sometimes on weekends he embarks on raucous camping expeditions outside Madrid with his few, informal Spanish acquaintances. It is on one of these trips that he meets the beautiful Isabel, his first Spanish girlfriend, with whom he begins to feel, prematurely, that he is bridging the cultural divide. Occasionally he suffers debilitating panic attacks, which he rectifies with tranquilizers and phone calls home to his psychologist parents in Topeka, Kansas. But, as mentioned above, Lerner is at least subconsciously aware that these incidents are to a degree muted, thanks to the “little white pills” he takes daily.

At first, it is easy to despise Gordon. From his affected reticence about his Brown University education (in Atocha he refers to it exclusively as his time “in Providence”) to his universal loathing of the other young Americans he encounters in Spain, Gordon is a spot-on portrayal of a now familiar twenty-first-century American type: the privileged liberal arts graduate in aimless pursuit of the next chapter of his education on the Continent. But the reader’s dislike of Gordon soon begins to dissipate, at least to a degree, and for two reasons. First, as the book proceeds, it becomes obvious that Gordon thoroughly despises himself as well. Secondly, and more importantly, in Lerner’s artful telling one gradually comes to empathize with Gordon. This mechanism of negative readerly identification with self-obsessed characters who are at once vain, blind to their privilege, and not-so-secretly self-loathing is, after all, how the serious künstlerroman – the artist’s developmental novel – has always worked. Like other künstlerroman protagonists, such as Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus or the early Nathan Zuckerman of Philip Roth, Gordon’s frankness, which is a kind of innocence, comes to strike a chord with the reader who, by the very fact that she is reading Atocha in the first place, and regardless of her particular socio-economic background, surely has more than a little in common with the aspiring poet Adam Gordon.

What Gordon is actually doing in Spain is of course more than a little ambiguous. Throughout the novel, it is difficult to know what Gordon means when he refers to his “project.” In the early days of his fellowship, his task appears to be primarily one of language acquisition: “My plan had been to teach myself Spanish by reading masterworks of Spanish literature and I had fantasized about the nature and effect of a Spanish thus learned.” But every time he picks up Don Quixote he turns to Tolstoy in English instead, or to writing wild “translations” of Lorca’s poetry. Gradually these translations, which are Gordon’s’s own poems far more than they are faithful renditions of Lorca, earn him a small notoriety in the Madrid poetry scene.

When it comes to his social life, Gordon is also thoroughly aloof. The hash, the novelty of the Spanish capital, and the company of a few loose acquaintances are enough to sustain him at first. But as the featureless expanse of his fellowship year spreads out before him, inevitably he finds himself subject to loneliness. And because he cannot admit that his problem could be so simple and un-poetic, sublimation begins. Gordon is straight, but he finds himself wandering in Chueca, Madrid’s gay neighborhood, a district so crowded and lively that “it was easy to mill around in such a manner that people on your right assumed you were with the people on your left and vice versa.” This is how he meets and ingratiates himself with Arturo and Teresa, two friends who help Gordon penetrate Spanish bohemia. Soon he finds himself compulsively lying, for sympathy and intrigue. For example, on a lark, he tells Teresa, a wealthy, aspiring Spanish poet who is several years older than him, that his mother has just died. When this earns him a fair measure of attention, he decides to tell the fiction to his current girlfriend Isabel as well. These lies escalate and prove unsustainable. But unexpectedly, his friends, even Isabel, don’t really care. In fact the lies work to enhance Gordon’s reputation as a character of intrigue and depth. Across the line of cultural difference, they perplexingly signify in his favor.

The experience is the same for the reader. Usually when a narrator or poetic speaker is found to be a compulsive liar, he becomes a fundamentally untrustworthy character, whose expressed deceptions imply other, unstated crimes (think, for example, of the Duke in Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” or of Coverdale in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance). The difference here is that never in Atocha does Gordon give off the impression that he is lying to the reader. This is one of the novel’s most distinctive accomplishments, and is, to a different end than in Browning or Hawthorne, a source of some of the richest formal resonances of the work. Atocha is an exceedingly frank, confessional novel; the presentation implies that by the time of its (Gordon’s) narration Gordon has outgrown his period of deceit and speaks with a sincerity and honesty about his previous lies and their effect. In permitting his narrator to speak truthfully about his social transgressions, it might be said, Lerner creates a kind of overeducated, anti-depressed, postmodern Huck Finn. Like Huck, Gordon’s innocent pursuit of worldly adventure is unselfconscious and a little crass. But it is also radical in its frank telling, which is an extension of the innocence behind his actions. Lerner thus purchases for his narrator a most rare brand of narrative authority: that of the fallible narrator whose fallibility must be trusted, in which we learn something of human experience in all its broken complexity.

The central action of the text, and the trigger of its most pronounced character development, centers around the bombing of a commuter train by Al Qaeda at the Atocha Station in Gordon’s neighborhood in March. The Madrid bombings, you will recall, were designed in part to influence the Spanish elections, to sway votes away from outgoing prime minister José María Aznar’s pro-U.S., pro-Iraq War successor, and toward the anti-war Spanish Socialist Workers Party. Al Qaeda was successful in this, and the political effect of the bombings on Spain, which removed Spanish troops from Iraq shortly after the election, was more or less opposite what took place in the US after the 9/11 attacks. Gordon, despite his frequent disavowals of American hegemony, does not find himself moved by “3/11.” His concerns are mostly that he further ingratiates himself with Teresa and her friends. He goes to a protest, but feels awkward participating: “Teresa and Arturo and Rafa were chanting, so I chanted too, but my voice sounded off to me, affected, and I worried it was conspicuous, that it failed to blend. I couldn’t be the only one not chanting, so I mouthed the words.” Although Gordon usually identifies himself with the left throughout Atocha, his apathy takes on a defensive appearance to those galvanized by the attacks in Spain, negatively associating him with American political dominance.

Gordon’s narrative ends with him mystified by the Spanish, evading, rather than confronting, the political responsibility he half-admires and half-resents in his Spanish friends. In this sense Atocha leaves the reader wondering about the risks of dwelling for too long in a space of suspended identity and politics. Cultural misunderstanding can produce unexpected social intimacies in Lerner’s novel, but larger historical and political tensions are not resolved so easily. At the same time, Atocha’s lack of resolution underlines another important aspect of this novel, its faith in the power of poetry, not to mention its frequent beauty as a work of literary art. The novel seems to insist on its status as art, in fact: if the ending proves that Gordon’s aesthetic idealism trumps his political engagement, he can at least be understood as engaging in another, perhaps no less significant, sense. For the text’s existence implies that Gordon went on, of course, to document cultural misunderstanding and personal pain. Indeed, although the book takes the liberties of a work of fiction, it does sometimes have the appearance of documentary, including perhaps half-a-dozen photographs, scattered throughout the volume, of Spanish people and places as well as film stills and shots of paintings mentioned by Gordon in the narrative. Evoking the strange, beautiful documentary “novels” of W.G. Sebald, this impulse to make a narrative scrapbook of lived experience, in its own way, may be viewed as a political act.

But the lasting argument Lerner makes in his novel is about literature, and is political or moral only insofar as it seeks to meditate on the relationship between poetry and real life. Not insignificantly, the volume’s title Leaving the Atocha Station, is also the title of a poem by John Ashbery, whom Gordon acknowledges in the narrative as one of his masters. Obviously Ashbery couldn’t have predicted that the Atocha Station would be the site of a terrorist attack when he wrote the poem in 1962. But Lerner’s intention isn’t to rewrite the Ashbery poem as a novel, or to call attention to its admittedly portentous resonance with subsequent events (the poem occurs in the volume The Tennis Court Oath, and, for the superstitious, it is certainly worth a look). Rather it is to show how profane history maddeningly inflects poetic meaning, even though that meaning may have been forged with great care to last longer than the contingent rhetoric of a given political moment. Like Don Quixote’s irrational devotion to the code of knight-errantry, the honor and pity of Gordon’s persistent defense of poetry, in plain sight of its real-world irrelevance, is what Lerner wants his reader to register in the end.

A final representative instance, then, from Lerner’s postmodern “Defence of Poesy.” Not quite halfway through the novel, Isabel brings Gordon to visit one of her aunts outside Toledo. In response to this aunt’s rather serious suspicions of poetry, Gordon says, without explaining anything, “I, too, dislike it.” For Gordon’s Spanish listener, this is just more cryptic arrogance from her niece’s American loafer. But for the reader versed in modernist literature, this is barely buried treasure: a silent citation of a line from Marianne Moore’s most famous poem, which is titled, simply, “Poetry.” Indeed, Atocha might be thought of as a novel-length rendition of Moore’s reassurance (cited here for brevity’s sake as Moore’s much abbreviated 1967 version from Complete Poems):

“Poetry” I, too, dislike it.Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one dis-covers init, after all, a place for the genuine.

Kevin C. Moore is a PhD candidate in English at UCLA. He works on nineteenth- and twentieth-century American literature, and he is currently completing a dissertation titled The Rise of Writer’s Block: Myths and Realities of American Literary Production. His essay “Parting at the Windmills: Malamud’s The Fixer as Historical Metafiction” is forthcoming in Arizona Quarterly. He lives in Santa Barbara, California.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig