by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Dalkey Archive Press, 2011 | 360 pages

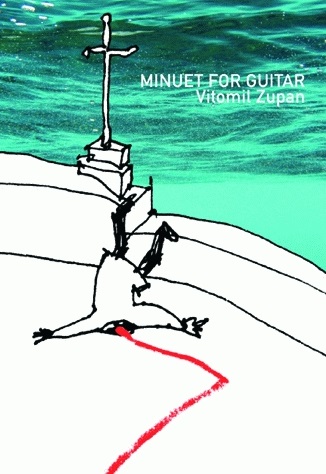

Originally published in 1975, Minuet for Guitar (in Twenty-five Shots) – considered by many to be the greatest work of Slovenian master Vitomil Zupan, and among the classics of World War II literature – begins in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, recently occupied by the Germans. The novel’s opening line – “Must head for the hills” – stands for the tone of the work as a whole, for Minuet is, in essence, an analysis of guerilla warfare, both that which is waged against an enemy on a battle field, and that which is waged against ourselves.

Minuet’s author, Vitomil Zupan, was born in 1914, in Ljubljana, then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the Second World War he joined the Liberation Front of the Slovenian People in underground activities against their Axis occupiers. He was captured and sent to a concentration camp, from which he escaped and rejoined the resistance. During this period he met literary theorist Dušan Pirjevec Ahac and assumed cultural duties for the resistance.

Minuet for Guitar, a semi-autobiographical work, is structured around two separate narratives which weave together as the novel unfolds. One focuses on the young Jakob Bergant-Berk, an opinionated, rash, self-centered, womanizing resistance fighter who, like the author, was captured and tortured in an Italian concentration camp before escaping to rejoin the guerilla fight against the Axis occupiers. Accompanied by an inexperienced and ill-equipped band of ragtag partisans, Berk spends much of the novel attempting to procure a better rifle. The second plot line, set in Barcelona in 1973, portrays an older, mellowed Berk, as he makes the acquaintance of one Joseph Bitter, a German who, during the war, had fought with the occupation against the Slovenian insurgency. Berk and Bitter discuss history, politics, philosophy, and – when Bitter’s loving wife isn’t around – the war.

“Happy the man who operates in harmony with the spirit of the age – and unhappy the man who is opposed to it.” So wrote Machiavelli, in The Prince. Likewise, a maxim that recurs repeatedly throughout Minuet states: “You don’t ask questions in the army!” Berk does not neatly align with this ideology, and Minuet for Guitar is in many ways a study of the clash of the individual and the military collective.

Zupan illuminates this theme primarily through character development, in two principle ways. Plotwise, there is Anton, a fellow partisan and foil of sorts who accompanies Berk in the World War II segments of the novel, as he drifts from unit to unit in the confusion in and between battles and ambushes. Anton is measured, wise, and thoughtful. He is the man, it seems, that Berk would like to be. A veteran of the Spanish Civil War, Anton’s experience with combat is Hemingwayesque, and he speaks of it with a nostalgia that Berk is looking for in vain in the hills surrounding Ljubljana. Minuet’s second means of developing character is structural, via the narrative jumps – between the present of 1973 and the past of 1943 – that fragment the novel. By way of these jumps we come to perceive Berk’s tentative evolution from a man ruled by impulse to a man self-determined by reason.

A comparison can be made to Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. In Slaughterhouse-Five, Billy Pilgrim comes “unstuck in time.” These jumps ultimately seem to be a defensive device by which Pilgrim shields his eyes from the horror of his setting, and accordingly Billy Pilgrim comes to be understood as a shell-shocked protagonist. Zupan likewise jerks his reader, with little warning, through time. But Minuet’s jumps are narrative jumps - those of memory - not ontological ones. He is not literally travelling through time. The difference is crucial and speaks to the different emphases of the two books. In Minuet, the jumps come to be understood to be a formal means by which to demonstrate Berk’s own evolving sense of self and other. Like Pilgrim, Berk is traumatized by his war experiences. Unlike Pilgrim Berk – through his friendships with Anton in 1943 and Bitter in 1973 – seems to have begun the process of recuperation, a process resulting from, and perhaps to some degree enabling, his newfound awareness that enemies of past wars may today be something other than what they once were.

Minuet’s resolution, to the degree that it does resolve, occurs in the shadow of perspective. It is the resolution of convalescence, of being made whole again in the awareness that in war the only difference between men is the color of their uniform, the direction in which they are told to point their guns. As Berk observes, “War was cruel and innocent at the same time… It is a dance, accompanied by a 25-shot guitar.”

SD Allison was born in Nebraska. He is the descendant of farmers, teachers, and men with bad lungs. He is the father of a little boy with autism. His first novel, Beneath the Plastic, was published in 2006.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig