by by Margaret Kolb

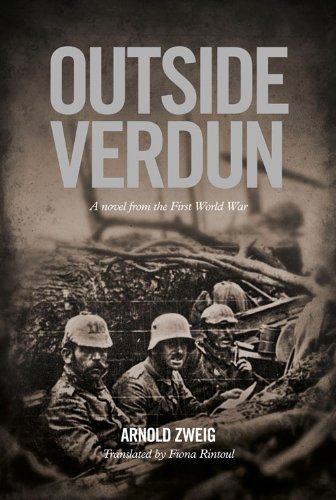

Published by Freight Books, 2014 | 405 pages

The year 2014 commemorated the centennial of the onset of hostilities in the First World War. There is, to be sure, no shortage of historical accounts of the epochal conflict. But with the exception of a handful of classics – All Quiet on the Western Front and A Farewell to Arms – the historical fiction of WWI has been conspicuously less well served. So much the more reason to celebrate Freight Book’s publication last year of the first English language translation in 80 years of Arnold Zweig’s autobiographical novel, Erziehung vor Verdun. In it, Zweig explores with depth and poignancy the forces that operate to make war possible, and in doing so reminds us of the cultural, social, and intellectual debt we owe to the great humanists that served and then wrote about that “Forgotten War.” It is a stark reminder of how much has changed, how much has not, and the interminable struggle of the human condition.

Arnold Zweig was born Jewish in Prussian Silesia (today Poland) and served as a junior enlisted Soldier in the German Army during WWI. Afterwards he returned to Berlin as a writer and journalist and joined the nascent socialist Zionist movement. With the rise of Nazism in the 1930s, Zweig went into voluntary exile, ultimately landing in Palestine. It was during this exile that he wrote his tetralogy of World War I of which Outside Verdun is the most notable volume. After World War II he returned to the Soviet zone in Berlin and, at the request of the government, served as a member of parliament.

Outside Verdun, translated here by Fiona Rintoul, narrates the experiences and thoughts of Private Werner Bertin during the 1916 battle for Verdun in Northern France. Bertin, as an enlisted Soldier in a labor battalion (read: not fit for combat), is at the very bottom of the rigid hierarchy of the German Army, but, by chance and force of his intellect and empathy, he becomes embroiled in a conflict of jealousy and reprisal between two well-connected officers. Amidst the chaos of one of the most bloody battles in all of human history, Bertin is caught in the political maneuvering of Captain Niggl – who is acting out of fear for his career and reputation – and Lieutenant Kroysing – who is exacting reprisal for the death of his brother. As a consequence, Bertin is shifted back and forth across the entirety of the battlefield, and through his eyes, thoughts, and interactions we experience the battle in panoramic, and the entirety of the WWI in microcosm.

Arnold Zweig’s autobiographical impulse, particularly his devotion to Marxist social theories and Freudian psychoanalysis, pervades this text. The novel is far more than a comment on the cliché “human cost” or “Soldier’s experience.” In fact, we could expect that Zweig would consider that interpretation insidious in its tendency to mask truth. Bertin’s journey is one of intellectual revelation through which the war acts as catalyst. The revelation is not simply – as some suggest – that the unimaginably devastating cost of war in blood, capital, and humanity cannot be reconciled with the hypocrisy, incompetence, and banality of its justification and execution. Rather, it is the revelation that war is merely symptomatic of a dark human psyche that acts on fear and base desire.

Outside Verdun opens with a brief narrative in which Pvt. Bertin gives water to a captured French soldier being marched with his company to their detention facility. For his kindness Bertin is subsequently reprimanded in humiliating fashion, marched before his unit and publicly scolded, and then scorned by his fellow Soldiers. In the subsequent chapters we meet Sgt. Kroysing who, like Bertin, was punished for questioning favoritism and theft in his unit, and was relegated to an isolated forward outpost. He and Bertin become fast friends, and when Kroysing is killed, Bertin travels to Billy (a French town) to attend the burial and meets Kroysing’s brother, Lt. Eberhard Kroysing. He is described as a revered, ruthlessly effective, and well-connected combat leader. Bertin gives him a letter that the deceased brother had entrusted to him days before he was killed, and speculates that his unit – particularly the portly and cowardly commander Cpt. Niggl - orchestrated his killing to look like a routine combat death in order to avoid the scandal of an impending courts martial. Eberhard and Bertin subsequently become friends, bridging the gap between officers and lower enlisted, and Eberhard begins using his influence and guile to exact retribution on Cpt. Niggl. Meanwhile, the war rages around them, injecting its chaos.

Zweig’s explicit Marxism surfaces almost immediately in the novel. In response to Pvt. Bertin’s punishment, fellow Soldier Wilhelm Pahl who offers a Marxist exploration of how, on the grand scale, such a magnificently horrible war could be waged by opposing armies of underprivileged troops without investment in the cause. He concludes that the war “allowed tensions within states to be redirected to the outside and meant that armies of proletarians, who might rise up against the ruling classes tomorrow, were busy slaughtering each other on the field of honor today.” Officers use titles and blood lines to justify their social position and exploitation of those who lack, and use hyperformal rituals, military necessity, and rigid hierarchy to maintain that position. Bertin’s innocuous display of humanity is punished to serve as an example to those who may be tempted to act outside their roles. Pahl’s rhetoric in this initial anecdote frames the novel.

Zweig endeavors to engage our senses to evoke his experience. His descriptions of the battered French countryside are rich in detail, contextualizing each pock marked building and blast crater with the offensive or initiative that created it. Every town and every building has a history and contributes to the identity and heritage of those that used to occupy them. We can smell the tension in the trenches, feel the despair in the eyes of the despondent infantrymen, and hear the fear of incoming shells. Zweig psychologizes his characters, and constructs detailed back stories and genealogies. We can see their uniforms and idiosyncrasies, hear their voices, and smell their brandy, wine, and cigar of choice.

Outside Verdun is in many senses both a work of literature and of history. As a novel, it is a refreshing deviation from what has become the template for full length fiction, particularly in the war genre.

As history, Outside Verdun is a wonderful counter-narrative – a precursor to the work of such resistance historians as Howard Zinn. Zweig corroborates what is historically known about the war in general and the Verdun offensive specifically. The German people starved in order to supply the front lines, the strategy at Verdun was to bleed the French ranks but ultimately failed because it bled both ranks equally and to no effect, and the leaders on both sides allowed the slaughter to persist for lack of courage to admit they did not know how to ‘win.’ Bertin’s intellectual journey illustrates how the experience of this war generated the social forces still operating in today’s world. Faced with unimaginable slaughter, all at the discretion of obtuse and arguably incompetent leaders, and devoid of any compelling justification or rationality, we understand how an intelligent and empathetic mind such as Bertin’s found answers in resistance and psychoanalytic ideologies.

The story ends with the death of Kroysing and Pahl. Bertin returns to Germany and reflects on how he would like to tell their parents “how miserable and pointless their deaths had been, so they might understand it was not some noble lie or bogus heroic sacrifice that had deprived them of the sons that would have supported them in their old age, but brutality and sheer, stupid chance.” Zweig intended for his work to expose the class structures that generate the “brutality” and “sheer, stupid chance” that deprives so many mothers of their sons and daughters. It is difficult to consider how, by his death in 1968, he assessed himself on that measure, but the project continues.

Adam Karr graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 2005 with a B.S. in International History, and this year earned a Masters in English from the University of Virginia. Adam also served a 14 month tour in Baghdad, Iraq and a 13 month tour in Nangahar Province, Afghanistan. He currently instructs English at West Point.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig