by by Margaret Kolb

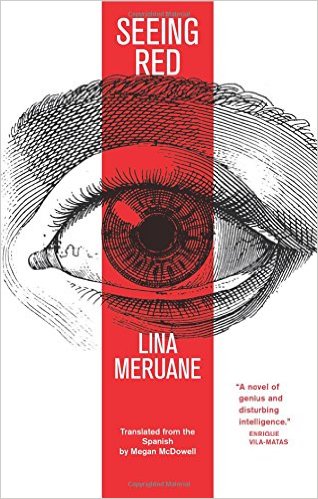

Published by Deep Vellum, 2016 | 170 pages

In the opening scene of Seeing Red (Sangre en el ojo), a young writer attending a party suffers a haemorrhage in one of her eyes that will leave her almost completely blind. The blood that seeps across her vision strikes her, in that moment, as beautiful, outrageous, and terrifying. As time passes, however, her loss of vision gradually builds into a blind fury. Having lost her sight, the protagonist ‘sees red’ – tiene sangre en el ojo – and experiences a desire for vengeance that turns out to be both uncontrollable and transformative. This sharp, surprising, visceral novel explores how illness affects creativity, the unbearable pressure it puts on personal relationships, and the surreptitious ways it can unravel our very sense of self.

Written by Chilean writer Lina Meruane and translated by Megan McDowell, Seeing Red has a complex relationship with autobiography. Like its author, the book’s blind narrator is a Chilean writer called Lina Meruane, who lives in New York with her Spanish partner, Ignacio. Able to see only light and shadows in the aftermath of the ‘firecracker’ haemorrhage, she awaits an operation that may or may not restore her sight. Meanwhile she is increasingly dependent on Ignacio, especially during their ill-timed move to a new apartment. The real Lina Meruane, flesh and blood author of Seeing Red – which received the prestigious Mexican Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize when it was first published in Spanish in 2012 – was diagnosed with juvenile diabetes at the age of six, and went through a three-month period of total blindness while doing her doctorate at NYU, where she now teaches on the Liberal Studies program. And yet whereas Meruane the NYU scholar is now fully sighted, Lina, the fictional character of her novel, remains blind over the period the novel covers.

Autobiography aside, further complexity is added when we realise that the narrator herself appears to be split in two: one character palimpsested over another. Self-made, self-sufficient New Yorker Lina has managed to partially efface the ‘Lucina’ of her Santiago youth by signing her novels with the abbreviated version of her name. With the advent of her blindness, however, this constructed identity begins to dissolve, and the layers of her self-hood peel apart. The protagonist speaks of herself as though observing from a distance: ‘There I am. There I go,’ she says in one scene, directing her words at Ignacio, who gets ‘tangled up’ among her names: Lina and Lucina. Elsewhere she interrupts her own narrative with parentheses––‘(You said, Ignacio, that’s what you said, even though now you deny it)’––and curtails her sentences mid-flow with unexpected full stops.

Central to Meruane’s novel is the degree to which its protagonist’s divided self is intricately bound up with her bilingualism and biculturalism. Lina/Lucina (like the book’s author) spent part of her ‘divided childhood’ in New Jersey, and expresses herself both in English and in Spanish. She remains a foreigner in New York despite her nom-de-plume, and yet does not feel at home in Santiago either. We witness a stark example of this when she travels to Santiago to see her family; a panic attack on the plane forces her to abandon Lina and morph back into ‘the Lucina who was me moving closer to Chile.’ As she feels Lina slipping away from her, she mentions her childhood:

In New Jersey, I’d forgotten all my Spanish. Later, in Santiago, I’d forgotten English. Now I’m forgetting myself.The analogy is extended when, in a Santiago supermarket, Ignacio’s foreignness renders him effectively ‘blind’. Here, losing one’s sight is equated to the experience of losing a language. He is unable to fathom the currency, and resorts to a kind of investigative work––‘hunting nouns’––in order to fill his basket, just as Lina had to hunt her way around their new apartment using only her sense of touch. Unlike in Spain, here ‘peaches were damascos and not albaricoques, peas were aruejas and not guisantes, beans were porotos and not judías.’

Holding onto language becomes a way of trying to anchor herself in a world without sight. During her panic attack, shaking uncontrollably and feeling herself ‘separate’ from herself, she counts slowly to one hundred, first in English, then in Spanish. Later, Ignacio does crosswords with her, ‘so we don’t forget words.’ Her thesis supervisor encourages her to finish writing her novel via dictation, warning her that by refusing to do so she is ‘making Lina Meruane disappear.’ Lina is resistant on this last point, as she feels that her visual memory is slipping away and is certain this will affect her ability to write.

What is perhaps most astonishing about Seeing Red is the degree to which its “perspective” is visual. Meruane once remarked in interview: ‘I thought I would write a novel that would have nothing visual in it, but what ended up happening is that the novel is completely visual’ (my translation). Eyes––an endlessly fertile conceit in literary history, but one that arises organically, and convincingly, here––are ubiquitous. Lina opens a window ‘like someone opening an eyelid.’ Her fingers have ‘their own lidless eyes on their tips,’ and her nipples are ‘the open eyes of my breasts,’ vividly depicting the way touch begins to take over the function of her lost sight. She describes ‘the tip’ of Ignacio’s body as a ‘blind, round, soft eye’ hidden under ‘a thick eyelid of wrinkled and secret skin’ that ‘sheds a tear, in spasms’ in her mouth. Most striking of all, perhaps, is a scene in which she ‘investigates’ Ignacio’s actual eyeballs, which induce in her a literal hunger for sight:

I started by putting my tongue in a corner of his eyelid, slowly, and as my mouth took over his eyes I felt a savage desire to suck them, hard, to take possession of them on my palate as if they were little eggs or enormous and excited roe, hard.This is our first glimpse of Lina’s sight-lust: urgent, physical, almost vampiric (she is already bloodthirsty, ‘seeing’ Ignacio fill her glass up not with wine, but with blood).

It is in response to this enduring hunger for ‘newborn eyes’ that Lina, despite herself, grows increasingly selfish and ungrateful over the course of Seeing Red, brooding on her own ‘dark purposes.’ She ‘sees red’ everywhere, but above all in the presence of Ignacio, who is transformed from her protector into her prey. During her trip to Santiago, she resists pressure from her family to return to Chile permanently, insisting that the only eye doctor she’ll trust to operate on her is in New York––even though that doctor can never remember her name, and does little to inspire confidence. The desired operation is necessary, she comes to believe, to re-establish a singular identity – she can only be Lina again, she says, ‘when my eyes let me.’ And so, some time later, when her doctor warns that a transplant is unlikely because eyes are rarely donated––they are too often felt to be repositories of memory, windows to the soul––Lina finally asks (or perhaps forces, it is implied) Ignacio to literally ‘lend [her] an eye.’ This, she argues, would be ‘the ancient proof of love,’ the thing that would unite them forever and turn them into mirror images of one another. What had been a relationship of utter trust and dependence, in which she ‘saw it all’ through his eyes, is transformed into something more predatory, gothic even, in a disturbing portrayal of the way the body’s illness can affect personality.

Though she has written three other novels, Seeing Red is Meruane’s English language debut. In a compelling, at times wrenching, portrayal of a bilingual life––with Megan McDowell’s deft incorporation of Spanish reminding us at key moments that the fictional world is inhabited in two languages––it explores, with extraordinary rawness and power, what it means to belong to a body, a person, or a place. Seeing Red is a novel about illness – about how the body’s failures can unhook us from our identities and push us to test the power of unconditional love. Yet it is also, perhaps more subtly but no less importantly, about what happens to our sense of self when we inhabit two languages, and for this reason it offers English language readers an outstanding introduction to one of Chile’s foremost young writers.

Ellen Jones is a Ph.D. candidate and Teaching Associate at Queen Mary University of London, researching English-Spanish bilingualism in contemporary fiction. She translates from Spanish into English, and edits the criticism section of Asymptote.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig