by Killian Quigley

Published by W.W. Norton & Company, 2011 | 364 pages

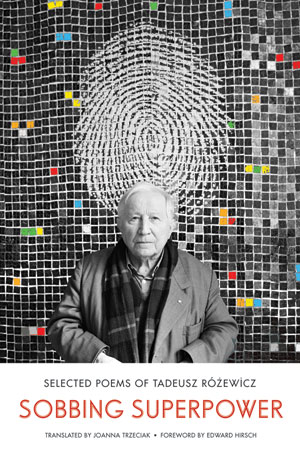

Born in a generation of writers that included the Nobel Prize winners Czeslaw Milosz and Wislawa Szymborska, Tadeusz Rozewicz (1921—) has been known as one of the darkest and most experimental voices of post-war Polish poetry. Sobbing Superpower, translated by Joanna Trzeciak, is the first extensive selection of his poetry to appear in English, and the only one that attempts to span the entity of Rozewicz’s poetic development.

It is hard to begin to describe the course of this development—as is the case with most of Rozewicz’s peers—without bearing in mind the historical context his poetry responded to and was often restricted by. Poland had regained political independence three years before Rozewicz was born. Less than twenty years later, it became the stage of some of the most harrowing events of the Second World War, fragments of which Rozewicz witnessed as a member of the Polish resistance. Poland was then incorporated into the Soviet block for most of Rozewicz’s adulthood, out of which it began bumpily to transition into capitalism when the poet was in his sixties. Unlike Milosz, Rozewicz did not migrate west to publish bolder political writing. Yet unlike Szymborska or Zbigniew Herbert, he also did not refocus his poems primarily around the abstract or the introspective. He could instead be described as a poet of the historically charged everyday: of ongoing attempts to persist in a community jostled by a series of historical events it had been unprepared for and which it continued gradually to process long after these events had passed.

The spaces Rozewicz’s speakers inhabit are tight and claustrophobic. Poem after poem attempts to carve out within these spaces a small moment of liberty or of joy, or merely of unabashedly transparent feeling. Rozewicz has been most famous for his earliest poems, which confront the trauma of World War II as he experienced it. The poems of his middle age deal with the deaths of individual friends and family members and with the economic scarcities and bureaucracies of Soviet Eastern Europe. His latest few books have spoken to emergent Polish capitalism, globalization, and at their most intimate to the poet’s own encroaching senility.

Rozewicz approaches these private or communal shocks with varying degrees of anger and suspicion. His poems about individuals (here, a dying woman) are often elegiac and tender to a point of extreme vulnerability:

These few lines present Rozewicz at his most powerful: disarmingly frank as well as disarmingly concise, his diction somewhere between the casual and the mythical. They also reveal the debt that Edward Hirsch is right to say (in his introduction to the volume) Rozewicz owes to Beckett. Rozewicz builds his represented world out of repeated theatrical gestures that seem at once expressive and mechanical, at once inalienable from the person who makes them and powerless to convey this person’s depth or essence in any meaningful way.I a godless manwanted to cry forth a meadow for herwhen dying and short of breathshe pushed awayat an empty and frightful netherworld

These moments of beauty are striking but dearly bought—bought, even here, at the cost of an emotional self-limiting that Rozewicz uses to highlight at once his personas’ historical context and their persistent inability to see this context with full clarity. There is a half-serious childishness to his subjects—a childish insistence about their right to live, to love, to be sensitive—that heightens the stakes of his confessional lyrics but also flattens the irony with which his speakers attack larger social and philosophical entities whom they blame for the individual’s disempowerment. His personas’ hatred of bureaucracies frequently spirals into an indiscriminate anger at social agency and social transformations as such, an anger that also folds back onto what his speakers perceive as their own social or cultural limitations.

Rozewicz himself is not unaware of the dangers (both political and aesthetic) of such indiscriminate frustration. In some of his most striking poems, he grapples with these affective and social constraints and challenges the reader who might fault him for them:

As one turns the page to this long poem (from which the above are just two excerpts), it takes a moment to realize how violently Rozewicz is trying to make us wince. His aim here, it seems, is no longer accuracy and empathy but a precise rendering of what Sianne Ngai has called “ugly feelings.” Rozewicz grotesquely amplifies and thematizes the mixtures of frustration, envy, fear, and self-hatred that animate his speakers throughout his work. He does so by turning to—on—Ezra Pound, a poet whom his persona cannot bring himself to trust but also obviously admires. The speaker alternately agrees with Pound’s contempt for 1920s capitalist Europe and accuses him of betraying both his art and the integrity of the later generations that would seek to imitate him. He alternately places himself above Pound and below him, styling himself as a stern judge, an envious impotent disciple, a mocking apparently ignorant child. The poem’s deliberate refusal of smooth aesthetic form seems both a question and a challenge: about whether it is ever possible to share social or creative agency equally, whether it is ever possible to exercise this agency without violence, whether it is ever possible to weigh the responsibility that particular individuals hold for its use and possession.Pound was a lunatic of geniusand a martyrHis most prized studentPossumwrote lovely poems about cats…P.S.too bad Pound had not yet readMein Kampfbefore he started to praisethe Fuehrer

Rozewicz lets the texture of such passages remain so rough that, even in Polish, it often takes much prior trust in the speaker easily to see beyond their first appearance of dilletantishness or naiveté. Reading Rozewicz’s poetry in English makes these risks of Rozewicz’s enterprise seem even more apparent. It also makes more apparent how much local historical knowledge one might need to understand the full subversiveness of Rozewicz’s anger. But there is a courage and a consistency to these poetic (self)violations as Rozewicz executes them that makes this cultural archeology seem worth undertaking.

To translate poems so strongly dependent on an aesthetics of the ugly is no small task; and though I occasionally disagreed with Joanna Trzeciak’s stylistic choices, her translation as a whole deserves much praise. Trzeciak deliberately, at times quite bravely, sticks to Rozewicz’s purposefully overgeneralized wording and mock-childish syntax. While her extensive notes do much to clarify Rozewicz’s specific cultural references, they take for granted much background knowledge about Polish culture in a way that occasionally makes her explanations seem slightly hermetic—or, in spite of themselves, addressed to an already familiar audience. That this locality should be so noticeable to the reader might in itself be merely a sign of the cultural suspicion into which Rozewicz’s poetry trains us; of the insistence with which he makes us question each term we might want to put trust in, each claim to social inclusiveness, goodwill, or authenticity.

Marta Figlerowicz is a graduate student in English at the University of California, Berkeley. Her criticism and creative writing have appeared or are forthcoming in, among others, Film Quarterly, New Literary History, The Journal of Modern Literature, Qui Parle, Dix-huitieme siecle, Prooftexts, Romance Sphere, The Harvard Advocate, and The Harvard Book Review.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig