by Simon Demetriou

Published by New Directions, 2014 | 64 pages

Look to the physical aspect of your manuscript…

On page 28 of Susan Howe’s Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives, I made an archival discovery. Whether it truly was a discovery is hard to say, for the textual material in question – a digital reproduction of a crop of a page of Noah Webster’s 1828 Dictionary – had already been chosen by Howe. But I still felt like I had found something, in a place at the periphery of her attentive, wandering gaze. Howe is grappling, on this page, with the idea that words are always already material, entangled bits of handicraft; hence, she isolates and reprints Webster’s entry for the word skein, “a knot of thread or silk wound and doubled,” with usages from Shakespeare and Ben Jonson. “That’s interesting,” I thought, agreeing with her assessment that each of Webster’s “terse definitions” resembles an austerely Calvinist prose poem. I prepared to turn the page. But then I saw the word directly above skein in her reproduction, (un?)intentionally captured within the frame of the crop:

SKE’GGER, n.s.

As the attribution indicates, Webster borrowed this definition from the English writer Izaak Walton’s Compleat Angler of 1653. And already we see the entanglements proliferate: Howe reprints Webster; Webster rephrases Walton; Walton records the folk knowledge of an untraceable infinity of anglers. To see this skegger is to see a skein, an entanglement. But also a skegger: a little thing, never thriving “to any bigness,” yet alive with abundance and packing a poetic punch. I wondered, in that vertiginous moment, if Howe had included skegger on purpose, letting the frame of the image extend ever-so-slightly beyond skein. Regardless, it’s in Spontaneous Particulars. And in the most striking way, it is one.

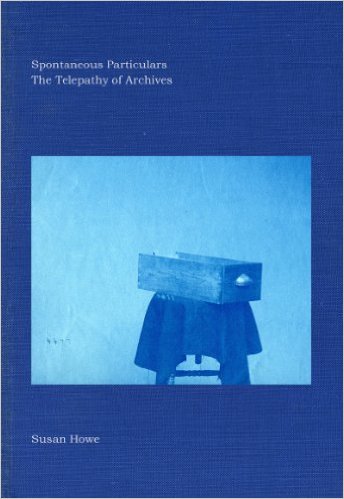

All poets are critics and all poetry is criticism, as Percy Shelley and countless others have maintained. Susan Howe is notable, nonetheless, for the lengths to which she has gone to put the two together. Like kindred spirits Anne Carson (Eros the Bittersweet) and Maureen McLane (My Poets), Howe writes poem-essays—or essay-poems—that explore how the self-enclosed openness of poetry can be an analytical tool: how a free-standing line, or image, or fragmentary piece of text, can argue and assert just as forcefully as a propulsive chunk of prose. Howe’s unique offering is her singular devotion to the archival materials of university libraries and special collections, which provide both the raw materials for her poetry and the urgency and responsibility that drives it. In previous books—most notably 1985’s My Emily Dickinson and 1999’s Pierce-Arrow (a critical resurrection of the American logician and philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce), Howe has striven to reconceptualize the intellectual, psychological, and ideological contours of familiar historical figures by attending carefully to their material traces: Dickinson’s fascicles and letters; Peirce’s diagrams and notes. Spontaneous Particulars is less a repeat performance of this process and more a meditation on her methodology. It is “a collaged swan song to the old ways,” an attempt to grasp what really happens when one enters the Rare Books room and communes with the skein-scraps of the dead.

All of which may make it sound like the book is about academic research – not quite. Although she spends much of her time in university libraries and has been a professor for years (she was one of the cornerstones of SUNY Buffalo’s famed poetics program, starting in the 1990s), Howe has always viewed herself as something of an outsider, or interloper, in the world of academia. As she admitted in a recent interview with McLane, “My entrance into academia was similar to a child’s being thrown into deep water to see if she will sink or swim.” As a result, Howe views her academic environs with a sense of detachment, and we often find her lingering on the structures and atmospheres of archival spaces which other academics generally take for granted. (At times she sounds as though she were a jewel thief casing the joint: Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, she writes, “was constructed from Vermont marble and granite, bronze and glass, during the early 1960s … Downstairs, in the Modernist reading room I hear the purr of the air filtration system, the rippling sound of pages turning, singular out of tune melodies of computers re-booting.”) From an existential and professional vantage point slightly outside the scholars around her, she reads the space of reading, the textures and sounds of reading itself.

Howe spends much of Spontaneous Particulars describing and re-presenting texts as objects, making a case for the archive as site of revelatory encounter. But the larger project of her book as a whole is to embody and model a different disposition toward these objects—looking in, looking aslant—that is still available to those of us inside academia, even if we unconsciously resist it. It is true that it is all too easy for scholars to pass through archives with the horse-blinders of scholarly purpose: we come to find something out, to find something “new.” We come burdened with the anxiety of discovery, a prescriptive rubric that carefully sorts everything we find into the useful and the not. Howe mounts an implicit corrective to this mentality in two ways. First she shows us that there is no “new.” Poets as visionary as Emily Dickinson and Wallace Stevens, thinkers as idiosyncratic as Peirce, were themselves archivists, collectors of bits and scraps. The search for new material is a fool’s errand. In a self-conscious way, Howe collects objects here that she, too, has collected before in other books. But she also shows us that there is a different kind of newness to be found in these old things, so long as we stop and look nakedly, without coercion, at what they are. It is the newness of the now, the immediate, the present: “This known world. This exact moment—a little afterwards—not quite—”. It is the living of the dead. To read Spontaneous Particulars is to witness Howe striving to articulate this “pre-articulate” space: over and over again, she tries to use words to convey something that is beyond words, even if it is precisely the feeling of confronting words in their material nakedness, in their prime, before they’re thrown into the spaceless abstraction of a typescript or an edited edition. (Or simply lost.)

Like That This, her previous book, which winnowed down from iterant, itinerant prose on the death of her husband (part 1) to geometrically variable cut-ups (part 2) to beautifully terse four-line poem-squares, Spontaneous Particulars searches for its subject – the archive encounter – by searching for shapes. The book’s literal and figurative centerpiece is a big circle: a manuscript by the 18th century American theologian John Edwards—one of Howe’s favorite ghosts, so palpable in the materiality of his remnants—written on scraps of silk paper his wife and daughters had been using to make fans. There are other shapes, too, presented with equal attention to their spatiality and materiality: the “raggedy scraps” of a diary by Hannah Edwards Wetmore, one of Edwards’ ten “unusually tall”—and all-too-easily forgotten—sisters; the ordinary rectangles of William Carlos Williams’ prescription forms, “used as fuel for the fire of poetic artifice”; the diagonal lines of a Dickinson envelope, structuring the words scribbled between them. Howe lingers on the shapes of these texts because shape is the first thing one sees when one unsheathes them from unopened folders and dusty boxes. Spontaneous particulars arise from these shapes: momentary epiphanies, the frisson of contact. Facing Edwards, Howe observes that “if you open these small oval volumes and just look—without trying to decipher the minister’s spidery script, pen strokes begin to resemble textile thread-text.” Facing Dickinson, Howe says: “Each collected object or manuscript is a pre-articulate empty theater where a thought may surprise itself at the instant of seeing. Where a thought may hear itself see.” But Howe’s “pre-articulate empty theater” also captures another crucial element of these encounters between text and self: they require emptiness. Not necessarily self-abstraction; Howe insists that “the inward ardor I feel while working in research libraries” is “a sense of self-identification and trust.” Emptiness—and a specific kind of emptiness, too: the blankness not of a blank page, a tabula rasa, but of a page already devoted (“prescription”) to the writing of other things. A willingness to make the mind blank, even as it races with prescriptive intentions: I am looking for this, because I know it contains that, because I need it to tell me this. A willingness to make the text blank, so that it can be filled with nothing less than what it really, finally is.

In a way, Howe’s project resonates with the appeal for “surface reading” that has been echoing in English departments across the country for the better part of a decade: the idea that we should read texts for what they say on the surface, at the level of basic semantic content, rather than reading “into” them, reading to prove a point. If anything, though, Howe asks us to read – with humility and reverence – a different surface, one that increasingly tends not to be a surface in the age of digitized manuscripts and OCR: the way the text-as-object looks, feels, maybe even smells – how it’s shaped, how it’s woven. Howe excerpts Webster’s entry for “skein” because it is a word for this surface, for the material surface of words themselves. That we find “skegger” in the crop’s margin, intentionally or not, only illustrates something else that’s crucial about the surface she wants us to read: it can only ever be found by accident. What we find in the archive, if we find anything, is by “the granting of grace in an ordinary room, in a secular time.”

Matt Margini is a PhD Candidate in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, specializing in Victorian literature and its animal representations. His writing has appeared in Kill Screen, Public Books, and Victorian Poetry. He often solicits wisdom from a blue crayfish named Papi.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig