by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Bloomsbury, 2012 | 176 pages

Swimming Home feels like a cliché. Set around a holiday villa on the south-eastern coast of France, it exposes British middle-class angst to glaring sunlight. The motifs of a conventional thriller are present and correct: a body in the pool and guns in the house, a marriage in crisis and a mysterious intruder, a speeding car and a mountain at midnight. The characters are archetypal, too: a cocksure poet, a war reporter, a teenage girl, a lonely neighbour, a handsome waiter. With these familiar elements in place, the novel teases us with predictions of a terrible event or critical revelation. Yet, when its climatic moment arrives, it is much stranger than expected – a twist which drives us back through the text hunting for additional clues.

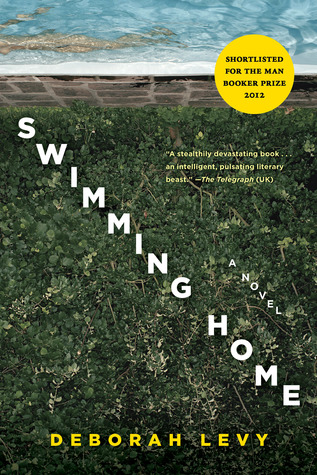

Born in 1959 in South Africa, Deborah Levy has been based in the UK since her family emigrated there in 1968. Swimming Home, her first novel for over a decade, has prompted an unexpected degree of critical and commercial success. Completed in 2008, it was initially rejected by many mainstream publishers because, in Levy’s own words, they considered it “too literary to prosper in a tough economy.” Eventually picked up by And Other Stories, an independent publisher with a staff of three, it’s now making its way around the world through reprints by major houses like Bloomsbury and Faber – aided, significantly, by being shortlisted for the 2012 Man Booker Prize. That a labored path was required for such a sharp novel is depressing, though it’s a reminder of how often small presses show up their corporate counterparts. One thinks of Tom McCarthy, whose first book Remainder (2005) – famously extolled by Zadie Smith as “one of the great English novels of the past ten years” – was rejected by several mainstream publishers, only to receive widespread acclaim after it was published by a small art press in Paris. Swimming Home comes with a brief introduction from McCarthy and it shares Remainder’s interest in questions of trauma, repetition, and death.

The notion of literary success is at the centre of Swimming Home itself. The novel’s crucial relationship is between two writers – one famous, the other flailing. The celebrated poet Joe Jacobs finds his family holiday interrupted by Kitty Finch, a flame-haired, frequently-naked woman in her early twenties, who harbours her own literary ambitions. Joe is married to Isabel, a journalist who specialises in international conflict. Despite Joe’s record of infidelity and the situation’s obvious temptations, Kitty is invited to stay by Isabel. The gesture is a crucial one: though she appears to come from nowhere, Kitty is, in a sense, willed into existence by the characters around her, a product of their own fears and desires. To further sharpen this Freudian edge, the action plays out around a holiday villa owned by a rich psychoanalyst and brimming with psychologically-charged objects. Also in residence are Nina, Joe and Isabel’s teenage daughter, and two middle-aged antique dealers from London. It is Kitty Finch, though, who grabs everyone’s attention. “The young woman was a window waiting to be climbed through,” we are told, in a metaphor that aligns Kitty with other uncertain surfaces in the text, like “the tinted windows” of a hire car, the “broken glass” of a damaged storefront and the “distorted reflection” of a face on the back of a spoon.

The swimming pool, nonetheless, remains the novel’s ultimate space of reflection and refraction, a perfect surface awaiting disturbance and a fixed frame for constantly shifting contents. While Swimming Home often charts an expected course – Joe and Kitty’s relationship becomes increasingly tense, Nina undergoes her own sexual awakening, the local French population observe the holidaymakers with amusement – it also repeatedly confounds our preconceptions. Just when the novel seems to be developing in typical fashion, an odd image or object will appear, like “a slap of waxy honeycomb half wrapped in a page of newspaper.” The enigmatic titles given to the book’s short sections – ‘Walls That Open and Close’, ‘The Thing’, ‘On the Way to Where?’ – further encourage the sense that this is a dream-like world.

While Tom McCarthy, in his introduction, emphasizes the connections Levy’s work has with “visual and conceptual art, philosophy and performance,” its most pronounced influence may be cinema. The floating, plunging and submerged forms in Swimming Home evoke a succession of filmic images – the bloody corpse of William Holden that bookends Sunset Boulevard (dir. Billy Wilder, 1950), the buff Burt Lancaster repressing his suburban nightmares in The Swimmer (dir. Frank Perry, 1968), Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate (dir. Mike Nichols, 1967) dreaming of a future beyond plastics, or the expressive sexuality of Ludivine Sagnier in Swimming Pool (dir. François Ozon, 2003). It is no surprise that Levy has mentioned Jean-Luc Godard and Luis Buñuel as inspirations for the novel, especially the former’s Contempt (1963), in which Brigitte Bardot’s bathing body is the subject of much fascination. Voyeurism – so intimately related to cinema – is also a constant presence in Swimming Home, whether it be a neighbour surveying the Jacobs family from her porch or Nina peering through a hole in a pebble. The novel’s structure feels cinematic, too. Though it moves in mostly linear fashion though eight days of sun and suspicion, Swimming Home contains strange repetitions, recurring flashbacks slightly amended each time they appear, which suggest that time is looping rather than progressing.

However, while all eyes are on Kitty Finch, it is death, especially in Joe’s “black oily past,” that increasingly comes to define the novel. The poet’s origins – he was born Jozef Nowogrodzki in the Polish city of Łódź, before being smuggled into Britain while his parents and sister were sent to a Nazi death camp – represent the dark heart of the book, a home to which return remains impossible, swimming or otherwise. Joe, we should note, is peculiarly aware of the “thing that could not be said” and a swimming pool, after all, is “just a hole in the ground. A grave filled with water.”

The final word, though, should belong to Kitty, the novel’s catalyst and, despite her apparent instability, its controlling presence. ‘Swimming Home’ is the title of a poem Kitty writes and presents to Joe. Levy offers us small chunks of this work, which is characterised by words “swimming round the edges of the rectangle of paper,” with the poem’s “sad and final message” only intimated. Joe concludes: “She was not a poet. She was a poem.” With her form and content unified, Kitty seems to be an exemplary modernist figure. The modernist ethos of Swimming Home is equally apparent: in unsettling fashion, it reminds us that a pool is just a hole in the ground, a poem is just a rectangle of paper, and language, like water, will forever frustrate our desires to grasp and control it.

Richard Martin completed his PhD at Birkbeck, University of London. He is now based in Berlin, where he is writing a book on architecture and cinema.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig