by Deborah Harris

Published by Penn State Press, 2012 | 272 pages

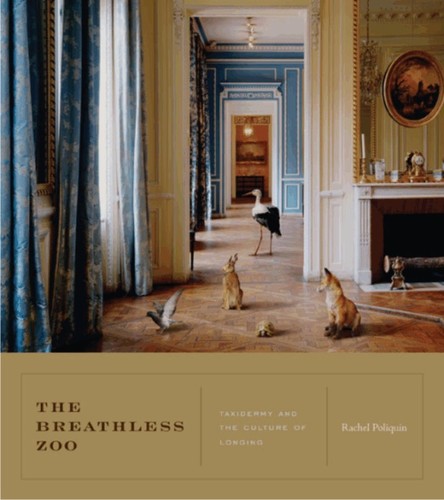

On February 25, an excerpt of a letter appeared on the taxidermy blog Ravishing Beasts, in which the writer confesses: “When I see taxidermy I get severe panic attacks. I have no idea why. It started when I was 4 and I don't remember a point in my life when I wasn't scared of taxidermy. It’s lead [sic] to extreme paranoia.” The letter writer is not alone in her dread of taxidermy’s spirited but motionless denizens. Taxidermy appears to us as something “mysterious, unsettling, provocative, and overwhelmingly visually magnetic”; it embodies numerous contradictory states—alive/not-alive, animal/not-animal, present/absent, life/death, beauty/repulsion, natural/artifice. Taxidermied animals, writes author, scholar, and occasional taxidermy curator Rachel Poliquin, exist “just beyond full elucidation.” The Breathless Zoo takes as its subject just this “beyond” to and from which we are simultaneously and so powerfully attracted and repulsed.

Part history and part critical analysis, The Breathless Zoo traces the evolution of taxidermy from its origins in natural history, through its transformation into a marker of wealth and taste, to its role as an expression of man’s mastery of nature, and, finally, to its current niche as eccentric, icky kitsch. Poliquin divides her text into seven chapters, each representing one of the “narratives of longing” taxidermy invokes: Wonder, Beauty, Spectacle, Order, Narrative, Allegory, and Remembrance. Despite the chapter titles, this book is no romantic paean to a dying art form, but rather a critical analysis of a very much extant cultural practice. Two central questions drive the text: why humans began to preserve animal carcasses in the 16th-century and continue to do so, and what these preserved “animal-things” subsequently become. In her investigation Poliquin finds taxidermy to be “deeply marked by human longing” — and revealing of human beliefs and desires, both of ourselves and of nature.

Today, taxidermy is generally viewed as “peculiar (read unexpected, off-putting, or downright disturbing),” but, as The Breathless Zoo chronicles, it was not always so. Poliquin begins her analysis with the blossoming of taxidermy in the 16th-century. Europe’s insatiable desire for objects from new and strange lands, she suggests, arose not so much from a desire for knowledge of the natural world, but instead predominantly out of the awe of nature’s “raw potentiality,” wherein every odd bit or piece offered the possibility of a new and as yet undetermined clue into the mysterious world of nature. Since nearly all attempts to transport exotic animal finds back to Europe failed spectacularly, the dead animals were instead brought back persevered either whole or in part. Seeing these frequently enigmatic fragments gathered in “cabinets of wonder” filled Europe with the sense that “anything might exist somewhere in the world, [in] any combination of parts, any size, shape, or structure.”

Through the 17th and 18th centuries and in particular by the Enlightenment, taxidermy methods grew in sophistication and began to play a key role in the proliferating field of natural history. European scholars like Carolus Linnaeus were enthusiastically working to impose systematic order on the seeming chaos of nature through taxonomy, a system for naming and ordering natural specimens. Naturalists needed actual specimens to measure, examine, and collect, to document new species and “determine... how it conformed to or disrupted established taxonomic schemes.” With imperialism in full swing across the globe, taxidermy provided the means of gathering just such specimens. Linnaeus, for example, had a large collection of preserved animals he used for his research. Taxidermy and taxonomy thus assumed key parts in the project to catalogue and master the natural, and human, world.

As the 18th century progressed, biologic taxonomy made swift progress, and the biological world was quickly mapped, named, and cataloged. Only then, Poliquin writes, when “nature [was] no longer menacing, when knowledge [had] achieved new heights of understanding, [and] when the wild beasts [had] been eradicated,” could domesticated nature become an aesthetic commodity. Thus, as taxidermy moved into the 18th-century, its intellectual cache led to its transformation into a marker of wealth and taste. Families bought, collected, and proudly displayed taxidermied animals as evidence of both their wealth, worldliness, and their knowledge and aesthetic appreciation of nature.

It was in Victorian Britain that “taxidermy reached its apotheosis” and became emblematic not only of the drive for scientific knowledge but also, and perhaps more powerfully, of the felt need to demonstrate the glory of the British nation and empire. By the 19th-century, stuffed specimens were to be found in many a neighborhood market and “any Victorian household would have at least one or two stuffed birds under glass.” During these years we find various manias arise and subside for particular taxidermied specimens. One of the more intriguing episodes the book explores is 19th-century Britons’ obsessive devotion to hummingbirds. Prior to the exploration of the Americas, hummingbirds had been unknown to Europeans, and the British found them simply delightful. Poliquin cites William Buck, who, writing about hummingbirds in 1824, proclaimed, “There is not, it may safely be asserted, in all the varied works of nature in her zoological productions, any family that can bear a comparison, for singularity of form, splendour of colour, or number and variety of species, with this the smallest of the feathered creation.” When an enterprising collector set up a temporary display of 320 species of taxidermied hummingbirds, more than 75,000 people flocked to get a glance of the wondrous creatures.

The Breathless Zoo moves from its exploration of taxidermy through the centuries to a closer inspection of popular kinds of taxidermy—hunting trophies, anthropomorphic taxidermy, and pet memorials—and what they reveal about human desires for and beliefs about nature. Of hunting trophies, for example, Poliquin writes that they function to give “bold and individual faces to the pervasive desire for animal death that underpins so much of culture.” Hunting trophies emphasize the unquenchable human longing to dominate nature and act out permitted forms of violence, and do so such that they both glorify and immortalize that desire while simultaneously pointing to the impossibility of its satisfaction. Anthropomorphic taxidermy, on the other hand, is examined as a representation of man’s dominion over nature in a rather different way. In this form of taxidermy, animals — typically small familiar ones like squirrels, rabbits, kittens, and mice — are dressed up and posed like humans in quaint little scenes. This practice epitomizes, for Poliquin, a means of demonstrating mastery over the natural world via mockery rather than accomplishment; its humor an “unsettling drollery” that suggests “flaccid allegories of human supremacy.” Anthropomorphic taxidermy expresses a sense that these small inhabitants “were otherwise superfluous to humans’ needs,” thus setting itself uniquely apart as a particularly “queasy material fable” that masquerades as whimsy. Finally, pet memorials – stuffing one’s beloved pet, that is – while evoking some of the same sense of sentimentalism as anthropomorphic taxidermy, represent yet another mode of human expression and domination. In order for a taxidermied pet to be a success, Poliquin writes, one must have both “an excessive emotional attachment” and “an indulgent disregard for loss.” Indeed, Poliquin argues that mistaking the stuffed corpse of a former pet for the pet itself either disturbingly conflates absence with presence, or, worse, suggests that what has departed—the soul of the animal—is not, in reality, much missed. Rather, it is the material body itself that is commemorated, and this, she posits, manifests longing as an expression not of devotion but of “the ultimate proof of ownership.”

If one were to find any fault with The Breathless Zoo, it would be with the book’s tendency, particularly in the early chapters, to become repetitive, especially in its frequent reiteration of its thesis that taxidermy concerns not nature itself but rather nature as we desire it to be. Current scholars of eco-criticism might also take issue with this assumption of nature as something real and pristine, something that exists somewhere just beyond human reach, as when, for example, the author writes that “nature is its own abundance and exists beyond ‘meaning,’ which is forever a human urge and imposition.” Such a belief about nature, it could be said, produces the illusion of nature as something tangible and “real,” and thus reveals a particular nostalgia for something we, in a virtual, postmodern world, can hold on to as a comfort, something that evokes the way things ostensibly once were and the way we believe they ought to be again.

Ultimately, however, The Breathless Zoo succeeds in its articulation of the many ambiguous ways in which taxidermy manifests the human longing to both represent and dominate the natural world. Poliquin, in careful and deliberate detail, makes commendable strides toward illuminating this very elusive and under-theorized practice, and in the process helps delineate how humans come to understand nature, or at least the contours of our desire for it.

Danielle McManus is a PhD candidate in English at the University of California, Davis. She specializes in 20th-century literature and is currently working on a dissertation exploring the application of queer theory to food studies. She’s a casual admirer of taxidermy and all things slightly odd.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig