by by Margaret Kolb

Published by University of Nebraska Press, 2014 | 86 pages

In 2007, Carla Bruni, first lady of France, former Italian model, and sometimes chanteuse, released No Promises, an album with lyrics comprised of the poems of famous poets including W.H. Auden, W.B. Yeats, and others. The lyrics to three of the songs were even taken from poems of Emily Dickinson, among the most singular and demanding of all poets, well described by Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant as "one of the rarest flowers the sterner New England land ever bore." This wasn’t the first—or last—time that Dickinson has served as a muse to French artists. Novelist Marguerite Duras and poet Claire Malroux, among many others, have professed Dickinson’s influence in interviews and in their writing. Without question, something in the poetic je-ne-sais-quoi of Dickinson, recluse of Amherst, agoraphobic genius, and kindred spirit to Rimbaud, has continuously drawn francophone audiences to her.

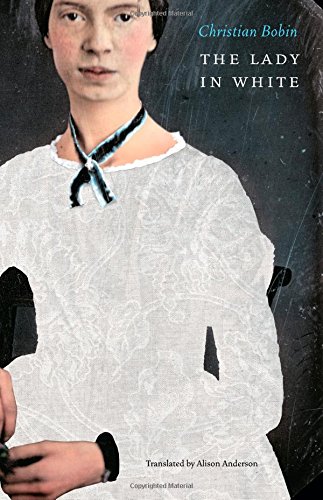

French writer Christian Bobin, recipient of the prestigious Prix de Deux Magots, is the latest French author to fall under the spell of Dickinson’s life and poetry and join this francophone tradition. In 2007, more than a century after Dickinson’s death in 1886, Bobin published The Lady in White – taking its name after not the dress she is most famously pictured in, but rather the snowy frock on display still at her house, now a museum – a fictional/poetic imagining of her elusive life woven from the scant facts of biography, painted in a style appropriate to Dickinson’s own elliptical lines: “A solemn thing—it was—I said—/A woman—white—to be.”

Emily Dickinson was born in 1830 to Edward Dickson, a lawyer-turned-minister, and Emily Norcross, a woman whose frigid demeanor was to have a profound influence on her daughter’s development, haunting Emily’s life, according to Bobin, with the memory of ancestral ghosts who “bent over her cradle.” The Dickinson clan was a prestigious one: Emily’s paternal grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, played a key role in the founding of Amherst College. Throughout her life, Emily maintained close relationships with her older brother, William (known as Austin), a judge and eventual treasurer of the college, and her younger sister, Lavinia (Vinnie). Apart from a brief period during her teens studying at the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, Emily lived her whole life at her family’s home in Amherst, baking gingerbread, writing poetry, and reading the works of her favorite authors (including Shakespeare, Hawthorne, Emerson, and Charlotte Brontë). Growing increasingly reclusive as the years passed, Dickinson communicated with the outside world (i.e., any place beyond the threshold of her front door) mainly through letters.

1862 marked a turning point in her life. In that year literary critic and radical abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson published the article “Letter to a Young Contributor” in The Atlantic Monthly, a solicitation for contributions to the magazine. Dickinson responded to his call by sending along a sample of her own poetry and the following question: “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” Higginson did publish a few of her poems and was to encourage and support her writing for years to come, but despite his epistolary mentorship, fewer than a dozen of Dickinson’s approximately 1,800 poems were published during her lifetime. After Emily’s death in 1886, Lavinia broke her promise to burn her sister’s papers (as Max Brod would later do to his own pledge to burn the writings of his friend, Franz Kafka). Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd, Austin Dickinson’s mistress, heavily edited the manuscripts (by regularizing her punctuation and syntax and occasionally rewording the text) before publishing the first significant collection of Emily’s poetry in 1890, with later series in 1891 and 1896. The first collection of her poetry to retain her singular punctuation of dashes and irregular capitalization (e.g., "The Eyes around – had wrung them dry – / And Breaths were gathering firm / For that last Onset – when the King / Be witnessed – in the Room – ") was published by Thomas H. Johnson in 1955.

In The Lady in White, elegantly translated here by Alison Anderson, Bobin weaves the threads of extant correspondence, poetry, and national legend into a dreamlike verbal tapestry of the poet’s life. It’s a biography without footnotes, a literary salmagundi made from snippets of Dickinson’s own poetry, details from family correspondence, and scenes gathered from Bobin’s own imagination—a telling, that is to say, that follows Dickinson’s own imperative to “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant.” The Lady in White, a slender volume which reads as a series of short, untitled epiphanies—the longest is two pages, and most are far shorter—opens with Dickinson’s death, when “Emily had suddenly turned her face to the invisible sun,” before retracing the quotidian moments and milestones in her life. Bobin’s zigzagging, lyrical prose illuminates what he imagines to be the forgotten moments of a biography too often corralled into a standard linear history: the lowering of gingerbread from a window to the neighborhood children; the luminous field of buttercups that bloomed during her funeral; the semi-erotic correspondence between Emily and her sister-in-law, Susan. Here he writes of “the heliotropes in the dead woman’s hands shone in the dark”; elsewhere, he details the hand of Higginson, “the chilly discoverer of Emily’s genius,” who journals his account of having just met Dickinson, as “the needle of the seismograph, recording every tremble of the invisible.” After the early deaths of several of Dickinson’s childhood friends, Bobin describes “the footbridge of life that creaked under young Emily’s step.”

Bobin limns the known facts of Dickinson’s life—her love of Antony and Cleopatra or the fierce temper of her father, whose silence could be like “that of a tomb”—but also plumbs into speculations as to murkier aspects of her life. In Dickinson’s semi-Sapphic correspondence with her sister-in-law, Susan, for instance, he discerns the pangs of an unrequited Eros: “The love between the two women must fracture, irresistibly, but the golden vase, even cracked, could still hold the water of a limpid word.” During her one meeting with the Atlantic’s Higginson in Amherst in 1870, Bobin suggests that Dickinson’s presence both exhausted and awakened Higginson’s intellectual capacities: “For the first time in his life he could feel the ocean of his brain pounding against the bony cliffs of his skull.” (This interpretation, it is worth noting, seems somewhat at odds with historical accounts, which cast Higginson as a critic blinded by 19th-century poetic convention, incapable of fully appreciating Dickinson’s innovative syntax in her “occasional poems.”) Other speculative love interests of Dickinson’s, including Reverend Charles Wadsworth and Judge Otis Philips Lord, also make cameos.

A devoted reader of Emerson, that “renowned thinker of the invisible” in Bobin’s words, Dickinson shared with him a spiritual and imaginative kinship. With her precise literary attention/affection to nature—"A Bird... unrolled his feathers / And rowed him softer home — // Than Oars divide the Ocean, / Too silver for a seam — / Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon / Leap, plashless as they swim"—Dickinson epitomized Emerson’s own philosophical metaphor: “I become a transparent eye-ball.” Unlike Emerson’s, however, her writings were less concerned with the forging of a national literary heritage. Dickinson’s citizenship resided instead in her own imagined country, which mapped, in Bobin’s tellings, onto her own yard and garden: “On the other side of the hedge was a foreign land—America. A brutal, naïve country…its stars threatened with extinction by a civil war…She did not belong to that world, did not want its war or its peace.” And while Walt Whitman wrote of the éclat of Civil War drum taps, Dickinson chronicled the invisible gash from a certain slant of light on a winter afternoon.

Dickinson’s agoraphobia resulted in the today unbelievable fact that though she physically resided in the geographic and socioeconomic vicinity of other American masters including Emerson and Thoreau, few of her great contemporaries knew of her existence. Bobin even recounts the remarkable fact that Dickinson stayed at home while Ralph Waldo Emerson paid a visit to her brother’s home, which could be seen from her bedroom window: “The acclaimed writers of her era…were unaware that they had gone to the wrong entrance, and that the greatest poet of the century was just there, in the house next door, behind a curtain of trembling lace.”

Somewhat frustratingly, the word hagiography is as fitting a description of Lady in White as biography. Bobin’s verbal worship of Dickinson fatigably enshrines her memory with phrases such as “saint of the everyday” and “handmaiden to the angels.” He frequently uses explicitly Christian language, which, even if an intentional referencing of her Calvinist upbringing and spiritual inclination, can feel distasteful, even inappropriate. She is, he writes, a “savoir” with a “cross to bear” who wears a “crown of thorns.” That such language arises as often as it does is all the more unfortunate for the fact that Dickinson, the subject of the excessive flattery, insisted more than most on the direct, unembellished engagement with things as they are.

The last letter that Dickinson ever composed contained, as Bobin writes, “two words falling from the dying soul, like snowdrops at the foot of a cherry tree: ‘Called back.’” As Bobin’s book so gracefully attests, Dickinson keeps calling her readers back—across oceans, across national borders, across centuries.

Nora Nunn is a PhD student in Duke University’s English department.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig