by Deborah Harris

Published by Bloomsbury USA, 2014 | 400 pages pages

In 1662, British forests were growing thin. Wars against the Dutch and Spanish had followed the English Civil War, and immense quantities of timber had been used to build ships. The British Navy approached the Royal Society, a group of London’s preeminent scholars (including Christopher Wren and Robert Boyle), to ask what could be done. The Royal Society’s response was spearheaded by John Evelyn, a British diarist – the celebrated diarist Samuel Pepys was his contemporary – gardener, and amateur forester. Two years later, in 1664, Evelyn presented his work to the Society and to King Charles II. His treatise was titled Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber in His Majesty's Dominions. Focused on the subject of trees, forests, their internal workings and proper cultivation, it advocated for the systematic, attentive, and scientific cultivation of forests to ensure their sustainability and productivity. Its publication marked the commencement of the modern science of forestry.

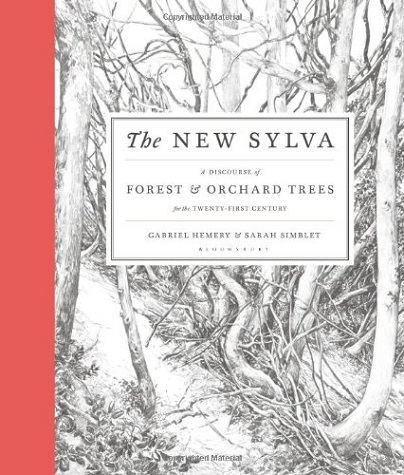

The New Sylva: A Discourse of Forest and Orchard Trees for the Twenty-First Century, a beautiful tome written by Oxford silvologist Gabriel Hemery and illustrated by National Gallery lecturer Sarah Simblet, begins with the following epigraph, taken from Evelyn’s original Sylva: “I did not compile this work for the sake of our ordinary rusticks, meer foresters and woodsmen, but for the benefit and diversion of Gentlemen and persons of quality…” Hemery and Simblet’s New Sylva, “an instructive companion [which] details modern approaches to planting and managing orchard trees,” is a wholly original work, but faithful to the spirit of the original. The authors strive “to present the art, practice and science of forestry and arborculture to a general public audience.”

The New Sylva is divided into five chapters: Of John Evelyn and Sylva, Of the Earth, Of the Trees, Of Silviculture & Forest Produce, and Of Future Forests. Of John Evelyn and Sylva provides historical backgrounding on the state of forests in the 17th century and the circumstances and genesis of Evelyn’s original Sylva. Hemery writes reverentially, advocating for Evelyn’s place as the founder of forestry. Quotes from Evelyn’s work are scattered throughout The New Sylva, revealing his foresight and effusive prose style.

Chapter 2, Of the Earth, provides a basic review of plant biology, and chapter 3, Of the Trees, details the 48 most important tree species in Great Britain. Each species is discussed individually and in depth, with subsections on biology and habitat; silviculture; timber and other uses; pests and diseases; and an assessment of the tree’s future prospects. Of the Trees is often quite technical, and Hemery walks a fine line between teaching the finer points of forestry and overtaxing his general audience:

Cedar of Lebanon and Atlas cedar are hardy to at least -20˚C, although they do not thrive in areas of Britain with high rainfall (above 1,500 millimetres per year). Both species are very drought tolerant, growing best on soils that are of poor or medium nutrient status. Cedar of Lebanon is light-demanding, and its broad, spreading canopy makes growing it in planation a challenge.At other times, however, his analysis makes accessible to the non-specialist reader the delicate networks at play within the forest. For example, the bark of the redwood tree is not only fireproof—the bark can, in fact, respond to fires by triggering the growth of a genetically identical tree from the original trunk or roots. The new trunk climbs alongside to the original, and, where they intersect, the two trunks can hold pools of water high in the canopy, specific ecological niches for diversities of species. Redwoods, Hemery writes, “support myriad mammals, birds, plants, invertebrates, fungi, mosses and lichens—so much life, in fact, that within a single canopy of a coast redwood, an entire ecosystem exists.”

Chapter 4, Of Silviculture & Forest Produce, brings us to applied forestry proper, introducing systems for maintaining a healthy, productive forest. The long timescales in forestry necessitate long-term planning and are unforgiving of improper management. Hemery notes the benefits of “close-to-nature” forestry systems that mimic the natural processes and dynamics found in non-managed forests; in continuous cover forestry, for example, trees are removed selectively so that large patches of land are never clear-felled and the canopy is maintained. This practice allows diverse tree species to be grown together, each complimenting the other’s growth. Shade also encourages slower growth, which produces better lumber.

While acknowledging that climate change will reshape the forest landscape—especially in an area as small as Great Britain—Hemery is optimistic that the outlook (at least for British forests) may not be wholly bleak. New tree species will be suitable for warmer summers and more temperate winters, and Hemery suggests that biomass—plant material used for energy—will gain popularity as non-renewable fuel sources are depleted. Nanocrystalline-cellulose, “a paste made from wood that could replace plastics and metals in man-made objects,” excites Hemery as well. Responsible forestry systems that encourage diverse tree growth – as opposed to single-species tree farms – promise to facilitate healthier and more sustainable forests, Hemery argues, and will be vital as new pests move north with warmer temperatures.

Since the origins of the environmental movement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries the discipline of forestry management has been divided into two general schools: "utilitarianism" or “conservationism,” on the one hand, and "preservationism" on the other. The former prescribes the active management and utilization of forestry resources for human consumption and profit; the latter argues against human intervention and for the preservation of forests in their natural, wilderness state. The most famous faceoff between the camps came in the early 20th century, pitting Gifford Pinchot, the first head of the US Forest Service, against legendary preservationist John Muir. In his book The Fight for Conservation, Pinchot wrote, “The first rule of conservation is that it stands for development.” Elsewhere he called for “producing from the forest whatever it can yield for the service of man." Muir on the other hand, a disciple of Emerson, wrote of his “unconditional surrender to Nature” and compared the damming of Hetch Hetchy, now a reservoir near Yosemite that provides water to 2.6 million Bay Area residents, to the razing of the greatest of cathedrals, “for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the hearts of man.” The debate rages to this day, both camps arguing that their approach is the only one that can ensure long-term forest sustainability.

Gabriel Hemery falls squarely with Pinchot in the utilitarian camp, arguing that managed forests are preferable to what he calls “non-market” forests: “A forest that pays is a forest that stays,” he writes. The only mention of preservation appears in the final pages, and there with some hostility:

Powerful organizations talk not of active management but of ‘preservation’ and their memberships are buoyant. Few bodies have the stamina to use the term ‘forestry’ and to celebrate the productivity of the woodland, especially when the roar of a chainsaw is associated, wrongly, with destruction and exploitation.It’s worth noting that the situation of British forests is different than that in the United States and elsewhere. Only 12% of Great Britain is forested, compared to 33% of the US, and Britain has no ancient (known in the US as “old growth”) forests, whereas a US census in 1992 counted over 10 million acres of old growth forest in Washington, Oregon, and California alone. It’s surely love that makes Hemery praise productive, and therefore secure, forests. Yet without an appreciation of the unique particulars of British forestry, some of Hemery’s pronouncements and distaste for “non-managed” forests will likely come across as abrasive to environmentalists who fall in the preservationist camp: “Instead of mourning the felling of a productive forest tree, let us celebrate the vision of the individual who planted and cared for it, then delight in its myriad products.”

Bloomsbury has spared no expense with this publication: The New Sylva as a material object is strikingly beautiful. Sarah Simblet’s pen and ink drawings trace gracefully across the book’s thick pages, depicting an expansive forest scene here, an elegantly twisting branch there. The New Sylva was honored with a British Book Design and Production award, and it’s easy to see why—all aspects of the physical text are delightful to handle and read. Its heft (5.6 pounds!) does, however, make it an impractical field guide. And it’s very handsomeness as an object threatens to encourage its being consigned to the shelf to preserve its condition. This would be a shame, as The New Sylva offers an insightful survey of forestry, of forests, and of the diverse ecosystems that call them home.

Jack Schiff is the Content Coordinator at Narrative Magazine. After graduating from the University of Maryland, he taught high school English in Houston. He lives in San Francisco.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig