by Ali Shapiro

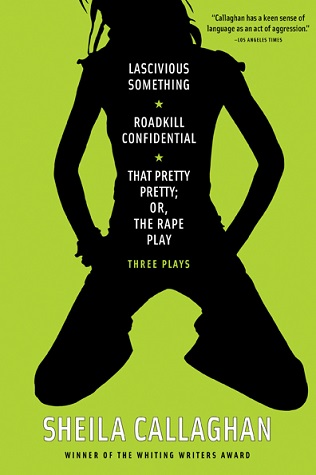

Published by Soft Skull Press, 2011 | 352 pages

“I bore easily,” admits Sheila Callaghan in the preface to her first collection of plays. “So basically, my aim is to write something I could actually sit through without clawing the flesh off my palms.”

To say that she achieves this (rather gross) aim would be a (rather gross) understatement: true, readers of Three Plays need not fear for their palm flesh, but Callaghan’s artistic achievements go much deeper than simple boredom aversion; the restless temperament exhibited in these plays provides relevant meta-commentary on the ADD-nature of contemporary entertainment itself. Callaghan seems keenly aware that she’s competing for our ever-dwindling attention spans with the rapid-fire editing techniques of the film industry and the instant gratification of hyperlinks, that choosing to go to the theater means resisting the crude, mindless allure of, say, reality TV. And so she tweaks her own medium accordingly, experimenting with stylistic leaps, unorthodox structures, and fantastical absurdities, and packaging it all under tabloid-worthy titles like Crumble (Lay Me Down, Justin Timberlake), Women Laughing Alone With Salad, and, from this collection, Lascivious Something, Roadkill Confidental, and That Pretty Pretty; or The Rape Play.

All this would be much less impressive if Callaghan sacrificed an inch of intelligence in the name of entertainment, but these plays are anything but mindless. When it comes to content, Callaghan is rigorously political in her envelope-pushing, boldly satirizing every headline issue from feminism to the Iraq war. When it comes to form, Callaghan’s stylistic leaps and experimental structures cleverly manipulate the seemingly inviolable continuity of time and space on the live stage, resulting in narratives that flit from present to past to fantasy to memory with the nonlinear fluidity of the human mind. That the contemporary human mind—driven to distraction, muddled by multitasking, perpetually channel and/or web surfing—would find this format particularly appealing is further testament to Callaghan’s genius. Both form and content draw our attention to the fact that we have stopped paying attention.

The first play in the collection, Lascivious Something, is the most linear of the three. Set in a remote Greek vineyard, the action revolves around August, an American expat and wannabe wine entrepreneur; his beautiful wife, Daphne; and his former flame, Liza, whose unexpected visit threatens to derail August and Daphne’s fragile peace. As in most love triangles, emotions run high—a fact made more explicit by Callaghan’s structural leaps, many of which serve to facilitate glimpses into a character’s stifled internal state.

Take, for example, an early scene in which August guilelessly pours three glasses of Bordeaux to celebrate Liza’s arrival, causing his glowering wife to storm off stage. Realizing his mistake, August reveals to Liza:

AUGUSTThe fact that August “does not notice” when Liza’s fist repeatedly “explodes in wine” is our primary clue that the glass-crushing is occurring on some other plane of consciousness; the casual replacement of each crushed glass with a new one, followed by the reprisal of “She’s pregnant,” signals the return to real-time reality. Though formally familiar from movies and television shows, this technique—cutting from inner fantasy to outer life—is harder to execute sans the magic of film editing. But Callaghan, undeterred, exploits the apparent shortcomings of the stage, to eerie effect: inner and outer realities seem to bleed into one another, as though these characters have been endowed with the enviable ability to rewind and redo their own lives.I totally, I completely…she’s pregnant.LIZA begins to hyperventilate. She crushes the glass in her hand. Her fist explodes in wine. AUGUST does not notice. LIZA retrieves another glass.AUGUST (cont.)She’s pregnant.LIZAI really like this wi—LIZA crushes another glass. She retrieves another.AUGUSTShe’s pregnant.LIZABut. She saw you take three glasses out, she didn’t say anything…

The concept of such a “take two” ability is deeply relevant to the thematic heart of the play, which Callaghan describes as an exploration of “the metaphysical map of the choices we make (and don’t make), and the ripples these may cause.” That the metaphysics here are ultimately rather grim becomes sickeningly clear in the play’s final “leap:” August, torn between two women, is able to “rewind” and try choosing first Liza, then Daphne, only to discover that the outcome is the same either way. No matter whom he chooses, August will not be okay.

Neither will Trevor Pratt, the leading lady in Roadkill Confidential, a play of such bizarre leaps and flights that Lascivious looks downright conventional in comparison. Trevor is a famous artist whose controversial work involves the eponymous roadkill (and whose surreal driving practices involve the nightly flattening of an Ark’s worth of critters, described in the stage directions as “the Hit Animal dance”). When a bunny-borne pathogen strikes her small New England town, Trevor finds herself besieged by a masochistic “FBI man” intent on proving she’s a bioterrorist.

As a political satire, Roadkill is saturated with allusions to censorship, profiling, patriotism, and other hot topics; as a cultural critique, it boasts a supporting cast of hilariously rendered archetypes. William, Trevor’s husband, is a blowhard academic whose understanding of art is pretentious and banal. Randy, their teenage son, is either extremely obnoxious or suffering from some form of Tourette’s; either way, he comes across as a poster child for the oversexed, fame-hungry, hollow rebelliousness of “today’s youth.” (He also spends a disturbing amount of time sharpening his fork collection.) Melanie, their pathologically perky neighbor, is an ignoramus in bliss, persistent in her naïve pleasantries despite Trevor’s tendency to respond with lines like, “Ah, Melanie, it’s you / For a second I thought I was hearing / the sound of a large inflatable latex raft / being squeezed through a tiny metal hole.”

Such a response epitomizes another oft-deployed leap—from realism to absurdity—which, while superficially humorous, is not without its own set of dark metaphysics. As in Lascivious Something, we’re faced with an unsettling blur; Callaghan flits from “real” to “absurd” with such disconcerting ease that the two seem more synonymous than dichotomous. Deep down, of course, we know this already—“reality” TV, remember? But that doesn’t make the implications any less troubling.

The real/absurd dichotomy goes further topsy-turvy in That Pretty Pretty; or, The Rape Play. The setting is “Anytown, America,” the time is “Now,” and the protagonists—Agnes, Valerie, Rodney and Owen—are effectively interchangeable. (The fifth player, oddly specific, is Jane Fonda, equipped with “circa ’82 leg warmers” and the ability to step in and out of the TV at will.)

The Rape Play starts off as your average girls-meet-guy, guy-follows-girls-back-to-their-hotel-room, girls-rape-and-kill-guy, girls-take-pictures-of-dead-guy-for-their-blog kind of story. (Take that, patriarchy!) But then things get really crazy. First, Jane Fonda shows up to lead Val and Agnes in a musical number. Then, and the play rewinds to the beginning—except this time the roles are reversed, with the guys taking the girl back to their hotel room, where they rape/kill/blog about her. (Take that, feminism!)

From there, the leaps only get more extreme, the language more brutal, and the political overtones harder to ignore. The Rape Play is basically a post-post-post-feminist meta-slasher flick for the Abu Ghraib generation—all of which is to say that no one comes out looking too good. Here, Callaghan blurs the distinction between rapist and victim, sadist and war hero, oppressor and oppressed—an attempt, she says, “to critique [antifeminist] images while simultaneously trafficking in them.” It’s hard to tell whither our sympathies should lie, and so the audience ends up feeling uncomfortably complicit in all the violence and abuse. Of course, positing this complicity—and forcing us to engage with it—is what The Rape Play is all about.

The play ends on an unexpectedly quiet note, especially considering that the penultimate scene includes the detonation of a grenade inside Valerie’s vagina. Owen is in the spotlight at what appears to be the Q&A portion of an artists’ talk. The subject of the talk is a play-within-the-play: Owen, it seems, has been writing his own script, the plot and themes of which bear suspicious resemblance to The Rape Play itself, and now his work has won some acclaim. We can’t hear the questions, only Owen’s answers—including relevant gems like, “I don’t think of them as ‘female’ characters. I think of them as people. I’m an observer of the human condition, irregardless of gender. I’m ‘gender-blind,’ as they say.”

This meta-theatrical conclusion feels almost like an implosion, like Callaghan has finally reached the apotheosis of her form: pure concept, pure wink, the playwright simply explicating, rather than dramatizing, her own ideas. If this move also feels like a bit of an anticlimax, well, so be it. The Rape Play contains more than enough climaxes, both literal and figurative, to convince the audience that Callaghan has pushed her various experiments to their logical (or, in some cases, gleefully psychotic) conclusions, leaving us breathless, enervated, titillated and, um, maybe a little bit sore.

Sore in the brain, that is. Because the zany, raunchy, random, shocking humor of these Three Plays belies their searing intellectual force, their cutting-edge political engagement, and the calculated skill with which Callaghan harnesses her restless energy to challenge, engage, surprise and entertain. Though capable of holding our attention as well as the juiciest episode of Desperate Housewives, these plays are truly mindful entertainment, conveying the most pressing questions of our era—ideological, political, existential—in our era’s native tongue. Callaghan puts the “value” back in “shock value,” the “culture” back in “pop culture,” and the “contemporary” back in “contemporary theater.” Adjectival responses may range from “delighted” to “outraged” to “nauseous” to “afraid,” but “bored” isn’t even on the spectrum.

Ali Shapiro is an MFA candidate a the University of Michigan. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in RATTLE, Redivider, and Linebreak, among others. She’s won various awards for her writing and other exploits, including a Dorothy Sargeant Rosenberg Poetry Prize and a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig