by Angela Moran

Published by Cambridge University Pres, 2010 | 324 pages

“Opera,” writes Herbert Lindenberger, “is the last remaining refuge of the high style,” while movies, according to Stanley Cavell, arise “from below the world.” Somewhere in the mix of high and low, old and new, epic and profane, elite and populist, and technological and pre-technological, Marcia Citron finds the subject of When Opera Meets Film, the latest of a recent flourishing of academic books that break ground on a substantial topic and a fascinating repertory. While opera scholarship has been around for centuries, and film scholarship is as old as the medium itself, only recently have academics (generally musicologists, though the philosopher Stanley Cavell is a commanding presence) tackled the peculiar courtship of two art forms that seem, on the surface, to stand at odds. How to reconcile movies, the exemplary twentieth-century art, with opera, whose grandiloquence and earnestness in the face of absurdity recall an earlier epoch? And how to relate opera’s distant faces and resonant voices to film’s whispered close-up?

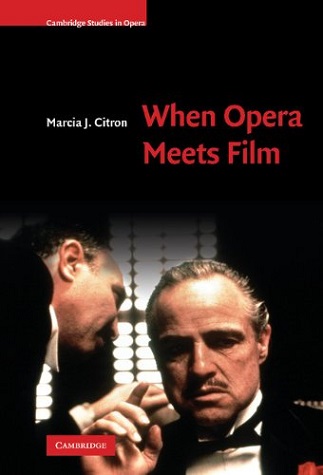

Citron’s latest contribution to the subject—she is also the author of Opera on Screen (2000), which focuses on complete filmed operas—considers a handful of movies whose rich connections to opera make them particularly interesting cases for study. These movies are either based on operas, include music from operas, feature operas in their plot, or are somehow suggestive of an operatic aesthetic—to be sure, a widely cast net. Whether or not a particular film makes one think of opera can be a subjective affair, though with the exception of Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather, which many have called “operatic” more for its texture and style than any specific reference to opera, Citron devotes her attention to films whose origin in opera is literal and unquestionable, such as the quasi-compilation film Aria, which is made up of ten filmed opera arias by ten different directors, and Claude Chabrol’s La Cérémonie, which employs the rare device of a televised opera as the centerpiece of its grisly plot. These movies’ debts to opera are so specific that Citron’s insights don’t have a lot of mileage elsewhere, though of somewhat broader implication is her discussion of movies that quote opera to express a form of desire, such as Moonstruck, Closer and Sunday, Bloody Sunday. Rounding out the collection is a chapter on the filmed operas of Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, a “major auteur of screen opera.”

Citron’s focused selection in this book allows her to comb finely through each film: no fragment of soundtrack is left unanalyzed, no interpretative possibility left unconsidered. In the chapter on Ponnelle’s opera films, for instance, Citron discusses the ways in which camera techniques (such as point-of-view shots, zooms and pans), the trope of doubling characters, and the use of interior singing (voices are heard but lips don’t move) allow the director to hypostatize subjectivity as a mode of understanding an opera and its characters. Through film, Ponnelle can do the (operatically) impossible: he can get inside Figaro’s or Butterfly’s head, show us what they think and feel, without relying on the power of a singer’s voice. The strange alchemy of film and opera is cast in the last two chapters as a productive tension between kitsch and grand passion, a distance which can be understood as (and perhaps also bridged by) the aspirational gap that defines desire. In Citron’s examples, the closeness and reality of film characters is constantly being projected against the idealism and heightened sensuality of opera, no less in The Godfather than in Moonstruck. It makes one wonder whether opera might be the perfect foil for film after all, since the distance between the two is so plangently evocative of human striving.

Opera’s affinity for film (or vice versa) might thus not be located in their similarity, but in their difference. As I read, I found myself wanting to hear more about this difference and what it might tell us. Citron’s remark that the Trumpet Motive in The Godfather “reminds me of the Shepherd’s Call played on the English horn at the start of Act III of Tristan und Isolde” is intriguing, but I would have been interested in Citron’s thoughts on whether musical motives have the same function or effect in opera and “operatic” film—does a melody played over a close-up have the same effect as one that echoes through a hall, for instance? Or when Citron compares blackouts in film to theatre’s falling curtain—their similarity is evident, but are they perhaps different, too? What do they have in common, and what distinguishes them? Finding connections between different beasts can be helpful in understanding them, but it can also lead to a loss of specificity and a priviledging of what is shared over what is different. It’s perfectly reasonable, for instance, to worry that musical repetition in a movie “risks neutralizing operaticness because something heard multiple times tends to lose its specialness as we become accustomed to it”—but what if we considered that thought against the examples of, say, Barry Lyndon or In the Mood For Love, intensely operatic films both (without a lick of real opera), whose obsessive musical repetitions show us how different film’s path to opera can be from opera itself?

The subject of opera and film provides such abundant, rich soil, and there is still so much to be said—indeed, we’ve barely begun. Citron’s four-page epilogue, in which she speculates about what “operaticness” might involve as a concept separate from any one medium or work, could itself be the subject of an entire book. Yet, before we get ahead of ourselves, there is a need for scholarship that lays the ground, offers good analyses of significant works, and provides steady footing for future enterprises. If Citron is right (and I am certain that she is), “the opera/film encounter is only going to increase.”

Dan Wang is a graduate student in musicology at the University of Chicago. He hails from Toronto.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig