by by Margaret Kolb

Published by McSweeney's, 2013 | 300 pages

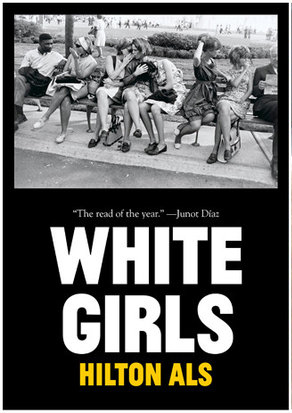

“Like most people,” Hilton Als writes in his essay “Tristes Tropiques,” “I respond to stories that tell me something about who I am or wish to be, but as reflected in another character's eyes.” And later, in “White Noise,” an essay on the autobiographical poetry of Marshall Mathers (a.k.a. Eminem): “For some artists—white as well as black—there is the sense that delving into 'otherness' allows them to articulate their own feelings of difference more readily.” For many readers, this otherness—central to White Girls, Als’s second book since The Women (1998)—may be what draws them into the text, because Als is other: big, black, queer. White Girls is a complex and quilted portrait of literary, cultural, and historical figures, all somehow complicated by otherness, from Truman Capote to Malcolm X to Prince to Richard Pryor, perhaps the centralist of fixations of our current society. It is a collection that spans genres—from fiction to nonfiction to cultural critique—and braids analyses of art, celebrities, gender, and race, among other subjects.

“Too often we refuse information,” Als writes in “The Women,” on Truman Capote's sultriness and self-feminization, “refuse to look or even think about something, simply because it's unpleasant, or poses a problem, or raises 'issues'—emotional and intellectual friction that rubs our heavily therapeuticized selves the wrong way.” Als’s text investigates this friction, and ultimately evokes a forced look at this friction within the reader—illuminates this friction within by analyzing the commonalities shared between the reader and problematized celebrities like Marshall Mathers, in particular his issues with women, or Michael Jackson, so sexually ashamed, etc. In general cultural discourse, we too often assume a distance from these stars' problems, assume that they're anomalous because they're stars. Als's investigation of celebrity gets under the reader's skin by looking deeply at these figures, as familiar as family to many, often deified, portrayed as unblemished.

Reminiscent in tone of Wayne Koestenbaum's Humiliation, Eula Biss's Notes from No Man's Land, Maggie Nelson's The Art of Cruelty, or the prose of Roland Barthes, Als employs the self in White Girls with deft skill. This is not surprising, as his text strives toward a similar form of cultural critique—displaying the influence of writers like Susan Sontag and Walter Benjamin. He writes in a cognizant third person, yet avoids complete self-effacement throughout the book by providing an I that's more often a lens than a subject, and raises overall questions about the role of performance in nonfiction.

In “The Women,” he writes that “Truman Capote knew—with the insightfulness of the writer who wishes not to be one sometimes and can step aside and see what his or her function as a writer means to others.” Als may catch what's funny here—he seems just as insightful as Capote, aware of both his function and his image. And whether he's writing on what makes him feel “niggerish” (as seen in the essay “GWTW”), or feminized, Als wants the reader focused on multiple subjects at once—himself, at times, being one of them, an effective formal means of further emphasizing the central role of otherness in the text.

“What is the relationship of the white people in these pictures,” Als writes in “GWTW” (acronym for Gone with the Wind) “to the white people who ask me, and sometimes pay me, to be a Negro on the page?” As is clear here, Als's performance is resonant because it's at once self-reflexive and familiar. His display and embodiment of otherness is the central theme that melds his subjects into the book's overall titular presentation: this is not a book solely about race, but about how race pulls other constructs (gender, class, sexuality) into itself. Learning about Richard Pryor or Eminem here are not only lessons about how Pryor was black and Eminem is white, but about what the white women in Pryor's life might say about himself as a person, or how Eminem, despite or perhaps because of his misogyny, is effectively defined by the women (mother, wife, daughter) in his life. Otherness, it seems, comes to define us all.

Als's text, as bold in concept as it is in its execution, skillfully brings bruises to the fore by contributing to the reader's understanding of subjects like gender, race, and sexuality. Perhaps he's merely highlighting these subjects' complications, but what Als seems to really want considered are the “bruises incurred by living”—and while these bruises are proof of pain, they're also proof of survival. Preserving the voice he's become known for as one of the New Yorker's sharpest critics, the overall presentation of White Girls is unsettlingly unforgettable.

Micah McCrary is a regular contributor to The Nervous Breakdown and Bookslut. His essays, reviews, and translations have appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Circumference, Identity Theory, Third Coast, Midwestern Gothic, The Essay Review, HTMLGIANT, South Loop Review, and Newcity. Former Assistant Editor at Hotel Amerika, he is a doctoral candidate in English at Ohio University and holds an MFA in Nonfiction from Columbia College Chicago.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig