by by Margaret Kolb

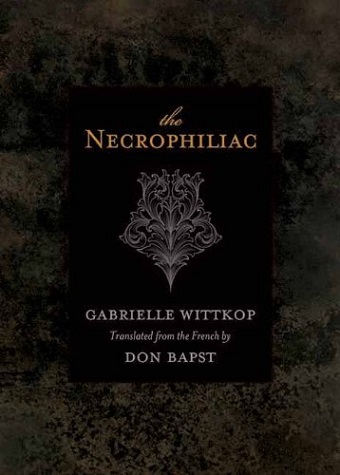

Published by ECW Press, 2011 | 91 pages

“You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style,” says Humbert Humbert, the pedophiliac protagonist of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. And murderers aren’t the only ones. Authors ranging from the Marquis de Sade to Edgar Allen Poe to Chuck Palahnuik have relied on similar tricks, juxtaposing the abhorrent behavior of their characters with irresistibly lovely language, daring the reader to fall under the poetic spell and into the seductive consciousness of every variety of sadist, fetishist and psychopath.

Thanks to translator Don Babst, the latest English-language entry into this macabre cadre is The Necrophiliac, a slim little volume by Gabrielle Wittkop. Wittkop, née Menardeau, is one notable exception to the tacit boys-only rule that governs this sort of extreme literature. Her biography suggests a history of transgressions in both life and art, from her marriage “of friendship and affection” to a homosexual husband, to her eventual suicide at 81 (she was suffering from lung cancer). She announced her intentions to her editor in a farewell letter: “I intend to die as I lived, a free man.”

Babst’s translation represents Wittkop’s first into English; the majority of her titles are available only in French or German (her native and adopted tongues, respectively). But from those titles—titles like “Sérénissime assassinat” and “La Mort de C”—we can perhaps get some idea of where her interests lie.

The Necrophiliac, Wittkop’s 1972 first novel, is structured as a series of entries in the diary of Lucien, the eponymous corpse-lover and owner of a small antiques shop. Describing his profession—“its cadaverous ivories, its pallid crockery, all the goods of the dead”—Lucien observes: “Truly, the occupation of an antiquarian is a situation almost ideal for a necrophiliac.” (40) Addicted to the intoxicating smell of “the bombyx,” plagued by a series of abdicating cleaning ladies, and begged by his tailor to wear something other than black, Lucien’s obsession renders him a solitary figure. Our view into his journal, then, is a peephole into a consciousness largely invisible to the outside world. As Lucien writes:

“[Necrophiliacs] have definitely chosen incommunicability, and their loves transcend into the inexpressible. Alone, we are not even the link between life and death. There is no link. For life and death are forever united, inseparable as water mixed with wine.” (18)One imagines this guy wouldn’t be too much fun at a cocktail party. And yet, Lucien is strangely charming, offering even the occasional gestures of dark humor. When a cleaning lady declares “that [he smells] like a vampire,” Lucien muses: “Always this old and aberrant confusion between two beings so fundamentally opposed as the vampire and the necrophiliac, between the dead that feed off the living and the living who love the dead.” (15) Our dear diarist is clever, to be sure, or at times wryly candid, as when he admits: “I can’t see a pretty woman or a handsome man without immediately wishing he or she were dead.” (26)

Alongside these moments of bleak wit, Lucien is also prone to waxing philosophical about his unique predisposition, and in this area he is a harsh judge—a perverse purist, but a purist nonetheless. On witnessing a stranger having his way with a dead nun, Lucien’s tone is undeniably condescending:

The little fellow was certainly not an inveterate necrophiliac, at most he was maybe among those who figure it’s never too late to start. In truth, I think it was more a case of opportunity making the thief, and he would have just as well appeased his brusque needs on a goat. (44)Lucien is an elitist, a connoisseur. And he has his morals, too—reminded of Gilles de Rais, the infamous serial killer of children, Lucien writes:

I don’t like Gilles de Rais, a man of a deficient sexuality, eternal little boy who never stopped committing suicide through others. Gilles de Rais disgusts me. There’s only one dirty thing: the suffering one can cause. (64)These morals are perhaps less honorable given their circumstance (what reminded Lucien of Gilles de Rais in the first place? The dead 6-year old child with whom he was taking a bath). Still, he has a point: the necrophiliac’s suffering, and his ecstasy, are only his own.

Such observations hint at the deeper loneliness at the heart of Wittkop’s book. In a sense, necrophilia is simply the human condition taken to its darkest extreme, a gruesome metaphor for the futility of sex-as-attempt-at-true-connection. As such, Wittkop’s rather facile explanation for Lucien’s fetish—an early masturbatory experience interrupted by news of the death of his mother—is hardly necessary; nor does it jive with the prevailing psychoanalytic theories, which attribute necrophilia to a desire for control and/or fear of rejection. In any case, whatever sympathy the reader comes to feel for Lucien is not the sort that stems from such justifications. No, that sympathy comes in the moments when we are lulled by Lucien’s “fancy prose” into almost forgetting that his affairs are so different from our own. Like any diehard (pun intended) romantic, Lucien too has that One Great Love, the one who got away, described in his diary with Nabokovian reverence:

Suzanne, my beautiful Lily, the joy of my soul and of my flesh, had started to marbleize with violet patches. I multiplied the bags of ice. I had wanted to keep Suzanne forever…As time passed and the dust deposited an ashy veil over everything, my despair over having to leave Suzanne grew…I told myself I should have taken Suzanne abroad…I should have had her embalmed and I would never have to separate myself from her. (37)Don’t we all suffer under the storm cloud of love’s transience, the torturous ephemerality of desire, the fear of loss? Don’t we all want to put our loves on ice, to preserve them, to make them last forever? Don’t we all hate when the decaying corpse on which we’re lavishing our most intimate attentions suddenly vomits black bile and—

And we’re back, again, in the gritty, visceral logistics that no prose flourish can hide. Clearly, Wittkop has acquainted herself with the finer points of her subject, and she describes the machinations of Lucien’s affairs in great detail. (It goes without saying that squeamish readers need not approach this book.) But as the brevity of The Necrophiliac demonstrates, Wittkop is also capable of restraint—that, or she just ran out of euphemisms for “decaying.”

In truth, brevity is vitally necessary to the success of Wittkop’s book. There are only so many variations on this theme, only so many dead nuns to be violated, and Wittkop seems well aware of the law of diminishing returns, of the need to keep upping the ante—and, finally, to quit while she’s ahead. Lucien himself deems his final affair—a torrid threesome in which he is the only participant with a heartbeat—the apotheosis of the necrophiliac form, and the climax (pun unintended!) comes just in time. Any longer and this book would simply be pornographic, or, worse, boring.

Ultimately, The Necrophiliac is neither. Graphic, yes. But the thrills here are anything but cheap, and the pleasure the reader derives is more cerebral than carnal. To read Lucien’s diary is to examine the darkest corners of human sexuality and morality, to question what it means to be alive in a body that seeks pleasure and connection with other bodies, to confront desperation and loneliness in their most lawless extremes. Wittkop’s unorthodox subject matter is what makes these themes resonant, fresh and utterly devoid of cliché. The Necrophiliac is a fast and mischievously satisfying read. Just don’t read it while eating.

Ali Shapiro is an MFA candidate a the University of Michigan. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in RATTLE, Redivider, and Linebreak, among others. She’s won various awards for her writing and other exploits, including a Dorothy Sargeant Rosenberg Poetry Prize and a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig