by Katherine Preston

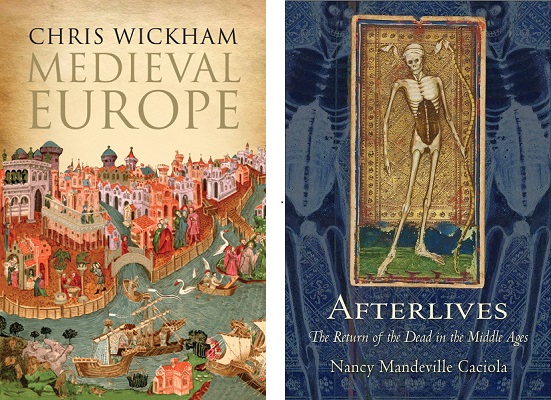

Published by Cornell University Press (2016), Yale University Press (2016), | 391, 352 pages

The Sack of Rome—the moment when, as St. Jerome put it, “the city which had taken the world was itself taken”—is the event with which most would mark the commencement of the European Middle Ages. An empire had fallen and another was just being born. Out of this geopolitical confusion emerged what historians have termed “the medieval period,” some thousand years of European history during which the unity of Rome gave way to a multitude of smaller counties, duchies, and kingdoms, populated by Germanic and Slavic peoples who had migrated west. Political cohesion may have splintered, but religion brought the peoples of the continent together—linking Bulgaria to Ireland—under the banner of the then ascendant Church. And all the while, we are told, civilization fell apart—life became nasty, brutish, and short.

Or so the story goes. Undoubtedly, these were, to our modern minds anyway, “dark” ages: a time when famine, disease, and poverty regularly reduced masses of human lives to dust in a matter of weeks; when doctors in long-beaked masks crammed with mint and dried, pungent flower petals crawled the plague-ridden streets; an epoch before the days of uniform legal equality. And yet, is our general conception of the period not a bit too simple? Do we not, in dishing out in a matter of sentences a concise summary of some ten centuries across no small fraction of the earth’s landmass, collapse a rich and diverse historical multiplicity into a two-dimensional caricature?

*

Christopher Wickham’s Medieval Europe argues this case forcefully. In it, we encounter a history of the medieval world in the full complexity of the economic, political, and religious transformations that radically altered European life over the period—a time and place no more or less complex, beautiful, and troubling than our own. Wickham’s text is, most generally, a survey of nearly 1000 years of history, conveyed in a quarter as many pages, spanning the period from the fall of Rome (c. 500) to the set of revolutions clustering around the year 1500 that collectively set in motion the modern period: the Renaissance, Guttenberg’s invention of the modern printing press, the confirmation of the heliocentric hypothesis, Luther’s inauguration of the Protestant Revolution.

Wickham’s magisterial volume balances sweeping narrative with geographical and historical particularity. In his history we witness such revolutionary developments as the emergence of post-classical learning, the cultural integration of peoples from outside the Roman Empire, and the emergence of medieval towns, those so-called loci for the later development of Marx’s primitive accumulation, not to mention the birthplaces of so much Renaissance art and banking. Wickham’s project, ultimately, is to re-familiarize the alien and to uncover the forgotten or neglected. Wickham’s text is rich in Oxonian attention to detail, effectively conveying the epoch’s incredible diversity, even as he refuses to give up on notions of shared cultural similarity. Riffing on Marx early on, he explains that such analyses of bygone times “require an understanding […] of the various actors in a very different but not unrecognizable world, as all history requires; although it is indeed important to recognize that the 980s were genuinely strange, with values and a political logic which we have to make an imaginative effort to reconstruct, it is equally important to remember that the same is true of the 1980s.” History, in other words, is always history, and knowing the past—whether Thatcher’s neoliberal Britain or Lothair’s late-Carolingian Francia—requires reconstruction.

*

“If you read these things often, you will be able to be a prognosticator.” Thus begins a section of a late-twelfth or early-thirteenth-century poem on the signa mortis, or signs of death. This line, examined in Nancy Mandeville Caciola’s Afterlives: The Return of the Dead in the Middle Ages, suggests the primary concern of Caciola’s text: how people understood and conceptualized death in a medieval Europe that predated modern medicine and, more generally, post-Newtonian cosmology. In large part, she addresses this question with regard to the afterlife. And not, it must be stressed, merely the Christian afterlife of purgatory, heaven, and hell, but also one in this world—the afterlife of incorporeal spirits and un-death. As Caciola shows, and as we find illustrated in the messages sought by the “prognosticator” of the signa mortis quoted above—who sought the means to ward off the possibility of a bad death (being buried alive, for example), to ward off the presence of ghostly hauntings and spiritual possessions—medieval doctors and peasants combined pagan myths of un-death with a desire for a Christian Sacramental end to produce a syncretic answer to the question of earthly demise. Thus the Christian conception of sin and the afterlife can seen to function both in light of the Christian cosmology and also in a more germane, practical sense: if the sickly and aged can be encouraged to die sinless and content, after all, they will be less likely to come back.

In Caciola’s analysis of medieval texts and ghost stories, the influence of Northern Europe and Southern Europe’s pre-Christian heritages come to the fore. In this sense, her work can be read as a history of the legacies of medieval Europe’s “pagan” ancestors, and the influence of their differing frameworks for imagining death and the afterlife upon medieval Christian thought. Historically, the Church first argued for a limited compatibility between Christian and pre-Christian notions of the afterlife, thus making easier the conversion of Europe’s pagan peoples. With time, however, it gradually undertook a project of ideological purification that culminated in the Scholastic project, often based out of universities, in the 13th-century Europe; here, learned theologians sought to more rigorously reconcile Christian and pagan narratives about spectral and corporeal afterlives into a single coherent Christian medieval cosmology. And all the while essentially-pagan folktales with Christian veneers proliferated, evolving over time into many of our ghost stories today. Caciola’s project thus expands beyond a mere attempt to clarify the roots of the diversity of notions of death and un-death in her period of study, accounting for the continuance of these pagan afterlives in our conceptions of death today.

Caciola’s text combines deep archival work with insights from cultural anthropology and attentive close readings of medieval texts, to shed light not only on the symbolic-imaginary landscapes of the medieval Christian period but also the material conditions of the life and death of the period. Her analysis of obscure poems and medical treatises sheds fascinating light, for example, on how medieval doctors scrutinized bodies for signs of possible physical demise:

Lividity appears in the extremities, with the front yellow-green

There is little urine, and raw food gets liquefied.

A very reliable sign is the contraction of the testicles

Or the retraction of the private part, the virile member:

These are signs through which the expectation of death is suggested.

Within the medieval purview, doctors had some ability to diagnose and treat physical illness. Great uncertainty, however, arose with the question of how they could guarantee that the dead person would never rise again—whether because of a misdiagnosis of earthly expiration (we ought not forget that medieval people lacked our complicated instruments for the prediction and confirmation of death) or on account of witchcraft or a liminal place in the spiritual economy. Indeed, Caciola regales us with tales of families haunted by relatives or friends, as well as stories of re-emergent cadavers, returned to warn the living of their misdeeds, signs of the rotten fruit of unchecked personal and social ills.

Whether it is The Night of the Living Dead (1968) as a commentary upon race relations—that constant and undeniable, repressed and ever-returning, specter of the American social consciousness—or medieval societies of dwarf kings feasting beneath mountains, whose presence serves both to protect and subvert existing social classes, stories of un-death have proved themselves adaptable. And that is what Caciola’s study, via her emphasis on micro-anthropology, best reveals: that even as the specifics of our cultural tropes change (even as they are genealogically related), they remain potent means by which societies interrogate and struggle to define themselves.

*

Caciola’s Afterlives: The Return of the Dead in the Middle Ages and Wickham’s Medieval Europe share in common a concern with preserving the variegated and complex nature of medieval Europe, with achieving a balance between narrow presentism and antiquarian fever.

Wickham’s study is the more approachable of the two, an introduction to an understudied period, written in lucid and, at times, inspiring, prose. Never boring, Medieval Europe functions primarily via the age-old art of storytelling, the relating of individual historical incidents to grand patterns and structures, the sort of bait that leaves a reader wanting to hear more—a not immodest accomplishment for a book of only 250 pages. Caciola’s work has more of sensational interest—bodies, plague, and the slow advance of cadaver armies—but is longer and more academic, technical. Even still, Afterlives is an enlivening read for anyone tickled by ghost stories or the recurrent need to represent the social unconscious; its occasional repetitions notwithstanding, it delivers on the author’s promise to “chart […] a history of the unknown: of pure, unslaked curiosity,” a quest as true of its illumination of medieval afterlives as it is of resourcing the medieval period itself.

These texts, which achieve an exemplary balance between the popular fetishization of the past and its complete and utter alienation, make accessible ideas that have for too long been relegated to scholarly journals, bring to light precisely what we need today: a Middle Ages accessible, but not flattened, a past unfamiliar, but not entirely alien. In triangulating problems at once theoretical, historical, and cultural, they make comprehensible the distance, and nearness, of the medieval age.

Chase Padusniak is a graduate student in the English department at Princeton University, where he specializes in medieval literature and critical theory.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig