by Angela Moran

Published by Oxford University Press ; MIT Press, 2014 ; 2014 | 264 ; 288 pages

I still recall the shock and disbelief I felt in tenth grade when, just halfway through playing Final Fantasy 7 on a borrowed PlayStation, the game’s villainous angel of death, Sephiroth, descended amid the sound of a funereal bell to murder Aeris, the mysterious flower-selling girl who seemed to hold the key to preventing the impending apocalypse (such are the machinations of games in this series). In hindsight, of course, what could be more trivial? And yet the music that followed—Aeris’s theme—gave her death a poignancy that belied its virtual nature.

Released in 1997, Final Fantasy 7 marks perhaps a midway point in the history of video games, between the astonishing virtuosity of present day games and the simple polygons and rudimentary bleeps and bloops of Pong, Asteroids, and Pac-Man. From the 1970s birth of arcade and Atari home gaming to the 1980s Nintendo-Sega wars to today’s PC, console, and mobile platforms, game creators and players have spawned a juggernaut of an industry, with close to $100 billion in worldwide annual revenues. This remarkable growth is due in part to increasingly sophisticated gameplay and graphics that have been matched by ever more impressive sonic palettes.

Game sound in its infancy was largely a matter of technological compromise. Favoring effects over music, programmers (typically not classically trained composers) sought to infuse their games with an aural dimension that would attract players in the noisy bustle of arcade parlors. With the development of dedicated sound hardware, music began making inroads; the four-note bass descent of Space Invaders (1978) is one of the earliest examples of continuous (looping) music. It took the introduction of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES)/FAMICOM and the Sega Master System in 1985, however, to bring to life video game music that has endured, thanks to the creativity—some would say genius—of composers such as Koji Kondo (Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda). Despite the persistence of short repetitive loops—a necessity given hardware memory limitations and the relative non-linearity of gameplay—the best game themes of this time are miniature masterpieces, both dynamic (reacting to a player’s direct input and specific game states) and musical. 4-channel sound chips synthesized stirring melodies and accompaniment, and it is a testament to this music that some video games and pop music of the present embrace chiptune’s 8-bit aesthetic.

The 16-bit era of the late 1980s and early 1990s (dominated in the United States by the SNES and Sega Genesis consoles) ushered in increasingly realistic timbres, sound effects, and stereo sound, all developments largely paralleled in PC game sound. Shortly thereafter, CD-ROM technology allowed for live-recorded—rather than synthesized—music, sound effects, and vocals, and the evolution of surround sound and positional audio offered the possibility of a more immersive experience with subtle sonic cues, information that became especially pertinent in shooter (Wolfenstein 3D, Doom) and stealth games (Thief, Splinter Cell). Even with the introduction of CD-audio, however, some games and systems in the late 1990s opted for MIDI-based synth sounds, for practical or aesthetic reasons. Today’s sound designers, composers, and audio programmers continue this negotiation of technology and aesthetics across multiple platforms, despite—but also, in part, because of—regular advances in hardware and software. AAA releases (those with the highest development budgets) commonly boast soundtracks of cinematic proportions—oftentimes by established Hollywood composers—while independent games often explore more minimal and experimental—but no less elegant and moving—sonic terrains.

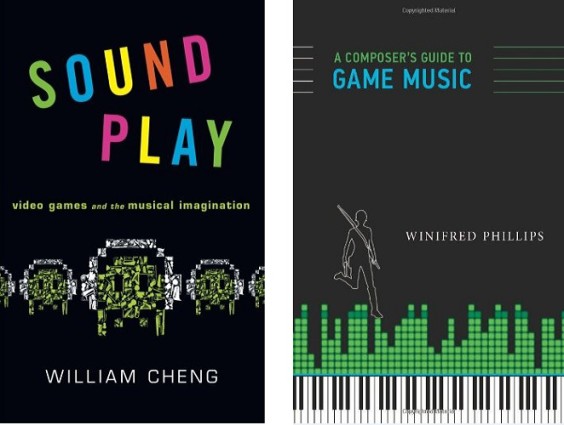

Two recent books, Sound Play and A Composer’s Guide to Game Music—written from the vantages of a musicologist and a successful game music composer, respectively—offer contrasting yet illuminating perspectives on game music and sound. Video games have gained increasing attention in academia over the past two decades. As young as video game studies are, however, the study of video game music is still more nascent. Video game music as a bona fide research area has been around for less than a decade; Karen Collins’s Game Sound: An Introduction of the History, Theory, and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design arrived in 2008, marking one of the earliest (and still indispensible) scholarly monographs on the subject. Only in the last few years has the field gathered momentum, with annual conferences devoted to the subject both in the United States (covered in 2014 by Wired Magazine) and Great Britain, and books by Kiri Miller (Playing Along); K.J. Donnelly, William Gibbons and Neil Lerner (Music in Video Games); and Peter Moormann (Music and Game), as well as additional books by Collins (From Pac-Man to Pop Music and Playing with Sound).

William Cheng’s Sound Play: Video Games and the Musical Imagination is one of the newest additions to this body of academic literature. It investigates, Cheng states, “how game creators, composers, and players employ (or otherwise come into contact with) music, noise, voice, and silence in ways that purposefully and inadvertently challenge social rules, cultural conventions, technical limitations, aesthetic norms, and ethical codes.” Both playfully written and remarkably interdisciplinary, Sound Plays asks readers to reflect on how resonances between music and games can enrich our understanding of each art form. Along the way, it explores the place of music and sound in the porous boundaries between the real and the virtual worlds, as well as the ways in which sound can raise and address questions of human agency through the player-avatar relationship.

One of Sound Play’s most compelling features is Cheng’s interfacing of theory and practice. He rejects, for instance, the notion of total immersion, a state of consciousness where belief is suspended and the real world is left behind as a player becomes perceptually embedded in the virtual world. Instead, drawing on work by game designers Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, Cheng relies on the idea of a “double consciousness” in which a player can identify with an avatar and still remain “aware of the character as an artificial construct.” This premise, among others, facilitates some of Cheng’s most sophisticated analyses, allowing him to investigate and reflect on the options that games present to players as well as the choices gamers make when confronted with these options.

The first chapter, “A Tune at the End of the World,” centers on Fallout 3, a 2008 single-player RPG (role-playing game) set in a post-apocalyptic United States. Here, Cheng delves into the potential meanings of the music presented by three different in-game radio stations, which represent all that remains musically after the unthinkable: some American hymns and anthems, 1930s and ’40s big band music, and classical violin repertoire. In this opening case study, Cheng charges with aplomb into the longstanding, incendiary debate over violence in video games, offering poignant reflections on the roles and relevance of music—and, moreover, musicology—in connection to violence both real (the American government’s post-9/11 use of music to torture and interrogate) and virtual (the author’s optional nuclear annihilation of an in-game town to—quite by chance—the climax of John Philip Sousa’s “The Stars and Stripes Forever”). Indeed, as much as Sound Play is geared toward gamers, it is addressed equally to the academy. Cheng admits early on that “Sound Play is at heart an enterprise in reciprocal critique…the book mobilizes its conclusions to reassess certain biases and rubrics entrenched in musicology, cultural theory, media studies, communications, and related fields.”

Cheng’s fascination with slippages between the real and virtual comes to the fore in the two chapters that follow. Chapter 2, “How Celes Sang,” turns to the 1994 Super Nintendo game Final Fantasy VI. Here, the emphasis lies on the game’s musical centerpiece, an elaborate and delightfully absurd opera performance rendered in an era before the rise of live-recorded, realistic digital sound. Cheng explores how the rudimentary, synthesized aria at the heart of the game’s opera (“Celes’s Theme”) has elicited such an outsized emotional response, manifested in YouTube tributes and live vocal-orchestral renditions of the FFVI opera. Through this, he offers a reflection on nostalgia and the interplay between disparate modes of spectacle. The third chapter, “Dead Ringers,” investigates the sonic transgressions of Silent Hill, a 1999 survival-horror game famed for its unnerving, immersive soundscapes.

The remaining chapters explore altogether different environments, focusing on two popular multiplayer online games: The Lord of the Rings Online (an Tolkien-based RPG) and Team Fortress 2 (a team-based tactical game). Chapter 4, “Role-Playing toward a Virtual Musical Democracy,” considers the practices and debates that have arisen as a result of the two musical systems included in The Lord of the Rings Online (LOTRO). Adopting ethnographic methods, Cheng uses interviews and virtual fieldwork to recount how real-world cultural values concerning musicality, performance, and virtuosity have spilled over into the game world, and how players—going beyond the developers’ envisioned use of in-game music as a virtual diversion—have employed music as a tool of harassment and territorialization. Cheng recounts, for example, how a group of impish players, in an act of musical griefing (antisocial behavior which intentionally disrupts another player’s gameplay), emptied LOTRO’s Bree-Town Auction Hall by playing six different bagpipe tunes simultaneously. While primarily about gender politics and agency in male-dominated online gaming, the final chapter of Sound Play, “The Wizard, the Troll, and the Fortress,” reveals how wide-reaching and porous the boundaries of musicology as a discipline have become, extending beyond music to include any and all sonic phenomena—including the very act of speech.

In contrast to Cheng’s more theoretical analysis of music within games as deployed sound, the focus in Winifred Philips’s A Composer’s Guide to Game Music is squarely on music, and in particular the process of its creation and composition. Composer’s Guide serves as a near ideal introduction to video game composition, balancing personal experience with technical explication. Although geared primarily toward composers interested in pursuing a career in the game industry, Philips’s book is accessible to those with only the most basic musical knowledge. She describes the book as “an exploration of issues relating to artistic inspiration within the confines of a game composer’s profession,” with her goal to “inspire creativity while pondering some big questions that confront game composers every day.” Composer’s Guide joins a number of other industry-targeted titles that offer advice on game audio, including Michael Sweet’s Writing Interactive Music for Video Games, Steve Horowitz and Scott Looney’s The Essential Guide to Game Audio, and Richard Stevens and Dave Raybould’s The Game Audio Tutorial.

The earlier chapters include discussions into how music functions in games, which musical genres pair best with different game genres, and what constitutes an effective musical theme. Chapter 3, for instance, centers on the concept of immersion. With recourse to numerous academic studies, Philips argues that music helps effect this psychological state. In contrast to Cheng’s theoretical approach to the concept in Sound Play,she presents immersion as the holy grail of gaming, one predicated on an empathetic and attentive engagement with the game’s narrative and characters. The later chapters of Composer’s Guide contain what is likely to be the most helpful technical information for aspiring composers. Philips covers the practical matters of a compositional career, including project preparation and workflow, the role of the composer within a larger development team, and the logistics of working as an independent contractor in the field. She also provides an introduction to necessary hardware and software, such as audio middleware applications that let composers and sound designers confer specific interactive properties to recorded speech, sound effects, and music.

Composing game music is a tricky business. Whereas film music can rely on fixed, linear narratives, most video game music is dependent on players, who advance through the game at their own pace. Composers, then, must create satisfying music that can be deployed in unpredictable ways. One solution to this problem is linear looping, and Philips delves into several ways of composing music that can loop repeatedly without fatiguing listeners—slow textures, perpetual development, and variations, to name a few. Another is interactive music that responds directly to player input, and Philips suggests multiple techniques—such as horizontal re-sequencing and vertical layering—for constructing reactive musical scores that integrate with gameplay.

Philips’s book is at its best when she illustrates her topics with reference to her own experience as a game composer, drawing on an award-winning body of work that includes God of War, Speed Racer, Spore Hero, Assassin's Creed III: Liberation, and LittleBigPlanet 2. Her explanation of the ideas behind the primary musical theme for Assassin's Creed III is illuminating, lending clarity to her somewhat idiosyncratic distinction between an idée fixe and leitmotif, both terms for recurring musical ideas. Throughout the book, Philips’s comprehensive knowledge of game music strengthens her points, as in her chapter on the roles and functions of music in games. Commenting on music’s ability to simulate a state of mind, for instance, she offers a range of examples, from her own post-minimalist-inspired score in SimAnimals to Rich Vreeland’s hypnotic soundtrack for Fez to Akira Yamaoka’s atmospheric textures in Silent Hill 4: The Room.

Elsewhere, Philips’s guide is less uniformly successful. In her myopic focus on immersion, for example, Philips seems to leave no room for music that runs counter to the visuals—sometimes referred to by film music scholars as anempathetic music. Film directors such as Quentin Tarantino have used audio-visual counterpoint to construct some of their most striking cinematic moments. To support many of the claims of the opening chapters—that video game music can alter a player’s perception of time, for instance, or enhance one’s awareness of visual details—Philips draws on a wealth of social science-based studies in video games and related areas, a tendency which at times threatens to overwhelm the larger points being made. Her discussion of music genres and game genres, for example, might profitably be boiled down as follows: mind your target market (for the majority of games, this seems to be one which prefers rock, orchestral/choral, or some fusion of the two). As thorough as Composer’s Guide is, some questions remain unaddressed. What do composers need to know about negotiating a contract? Are the compositional aesthetics for non-narrative, mobile games, which continue to gobble up market share, fundamentally different than those of narrative games?

In her brief conclusion, Philips takes up the by-now rather tired argument that video games can be art—contrary to the late film critic Robert Ebert’s perhaps-too-remarked-upon protestations otherwise. Yet despite closing her book by arguing video games’ artistic merit, Philips gives relatively little consideration to the question of the meanings that games—and their music—can create as works of art. To support her claims in this area, she might have turned not to the social sciences, but to humanities-based inquiries such as Sound Play. Here, scholars are exploring the aesthetic responses games provoke and how, to borrow Ebert’s language, video games might make us “more cultured, civilized, and empathetic.” Some argue, for example, that gameplay can introduce an ethical dimension by confronting players with choices which at times fall in the uncomfortable, gray area of moral ambiguity, prompting players to reconsider entrenched social values (for instance, what constitutes musicality and authenticity in an increasingly technologically mediated world).

Ultimately, both books encourage us to attune our ears and minds to the sounds of the worlds in which we move, whether real or virtual. At their best, virtual worlds afford opportunities unavailable or unfeasible to us in the real world: to act out and explore unfamiliar experiences, to find solutions to new problems, and to think deeply about the choices we make and, perhaps, even our own humanity. Along the way, sound—and music—deepens our engagement, comments on our actions, and guides our emotional journey. And, if we die (virtually) in the process, as so often happens in video games—well, there will be no mistaking for whom the bell tolls.

Ryan Ebright holds a Ph.D. in musicology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His research centers on music for the voice, stage, and screen, with a particular emphasis on contemporary American opera and nineteenth-century German art song.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig