by Simon Demetriou

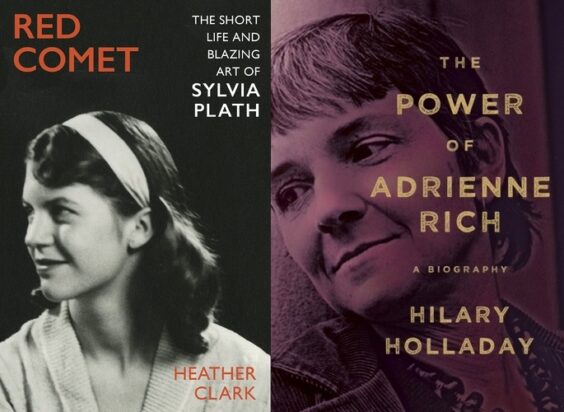

Published by Nan A. Talese; Alfred A. Knopf, 2020, 2021 | 496, 1184 pages

Sylvia Plath and Adrienne Rich hung out once at a party in Cambridge, MA. April 11th, 1958. Five years later, Plath would be dead after leaving the gas on in her flat in London, and fifteen years later, Rich would shift into her most famous mode, that of a radical feminist lesbian thinker. But in 1958, as both of their biographers argue, the two writers were stuck in a similar situation: that of the smiling, university wife.

It wasn’t that they didn’t have careers of their own. Rich’s first book had already been chosen by Auden for publication as part of the Yale Younger Poets Series, and Plath, though barely known as a poet, had published scores of short stories in women’s magazines, done the famous internship at Mademoiselle that would provide the material for The Bell Jar, and received a Fulbright to study at Cambridge. Neither of this mattered all that much to the society they kept: liberal men and women still stuck in the patriarchal mode of post-war fifties America. To them, Rich was the wife of Alfred Conrad—economist and professor at Harvard—and raising two children with a third on the way, and Plath was the wife of Ted Hughes, well on his way to becoming Poet Laureate of England.

The night Rich and Plath met in 1958, Hughes had given a reading at Harvard’s Longfellow Hall, and afterwards Jack Sweeney—the curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room—had a crowd over for cocktails. Plath in her journal later described Rich that night as “little, round & stumpy, all vibrant short black hair, great sparkling eyes and a tulip-red umbrella: honest, frank forthright (sic) & even opinionated.” Rich didn’t record what happened at the party, but W.S. Merwin noted later that Rich had “advised Sylvia very strongly not to have children.” In the Plath bio (900 pages) the story of the encounter takes up about a page, in the Rich (400 pages), about three pages. The stories of the two writers entrance, but the biographies themselves display two unfortunate tendencies of internet-influenced writing: the data-dump and the extended think-piece.

At 1184 pages (900 plus footnotes, and originally 1400!), Heather Clark’s Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath, is the data dump. It isn’t that Plath doesn’t deserve 1184 pages. That she wrote The Bell Jar and the poetry collection Ariel alone makes her life compelling, but Plath is also one of a handful of 20th century poets that non-poets read outside of a class requirement. In her case a biography is especially imperative, considering all the dumb gossip about Plath, her “craziness,” and Hughes’ purported atrocities. For those reasons and more Clark’s essential mission here is to set the record straight as to the facts of Plath’s life.

As it occasionally is with Plath, the life feels more important than the work. Do you want to know the name of every boy that Plath went on a date with in high school and undergrad? Are you fascinated by which stories and poems are accepted and refused by which popular magazines? Do you need to know who Ted Hughes drew up astrological charts for, and which charts he wouldn’t finish because he got bad vibes? Then Clark’s Red Comet is for you. Since Plath’s most notable work comes towards the end of her life, the book reads more like a teen drama than a literary biography. This doesn’t bother me one bit, but it makes somewhat glaring the discrepancy between the lack of substance Clark demonstrates in the work and Clark’s continual insistence that Plath’s work ranks as one of the crowning poetic achievements of the century. Clark has written critically about Plath’s work in the past, but what textual analysis there is in the biography feels, at worst, piecemeal and, at best, only in service of Plath’s tragic story.

Still, it’s astounding how much particular information you get about Plath’s life and how, by the end of the book, you have a sense of what the “real” story is. Essentially: an extremely smart and driven woman is never given the specific encouragement, possibilities, or community she needs to fully succeed, mostly due to her being a woman in the 50s and 60s. (Clark also goes out of her to largely acquit Hughes, without dismissing his faults). But, without more attention to the work itself, the biography suffers. I get it: a biography should be an argument about a life, not necessarily about the work. But the ultimate impression Red Comet leaves you’re left is that of a “crazy” life, not that of an astonishing literary achievement. And is that really the most important thing about Plath? Perhaps. Clark wants to separate the work from the life, and she makes a capable argument that Plath’s achievement in spinning non-fiction into fiction and poetry played an important role in literature’s slow march to auto-fiction. But the biography is more a record of a “short life” than a reckoning with a “blazing art.”

Whereas Clark’s biography of Plath provides the most granular account of all aspects of her life, Hilary Holladay’s The Power of Adrienne Rich only provides the broadest strokes of Rich’s life . Holladay duly reports the major plot points of Rich’s life—her early success, her marriage and child-rearing years, her husband’s suicide, and, eventually, Rich’s emergence as an important voice in feminist and lesbian writing. But while the story is conveyed well, Holladay—writing the first biography of the writer—leaves much in the dark as to Rich’s motivations for the various shifts in her life and thought.

Part of this is Rich’s fault. As a writer and thinker, she simply covered so much ground that it’s difficult to do anything but turn her life into a litany of causes. As Ange Mlinko noted in her recent review of the book in the London Review of Books, “the full range of Rich’s concerns – which expanded over the decades, from pacifism and racial justice in the 1960s to feminism and queerness in the 1970s to antisemitism and Marxism in the 1980s – has dominated public discourse in the wake of the Trump years.” By the time Holladay begins confronting one aspect of Rich’s politics, she is already moving on to another. There are, of course, real benefits to brevity. And Holladay’s 496 pages feels like a short essay contrasted with Clark’s 1184. All in all, though The Power of Adrienne Rich feels lacking in significant ways, Holladay ably compromises between telling a good story and letting Rich’s full life be portrayed.

Besides, if you want to trace Rich’s thought, why not just read the poetry and essays? What makes Rich so compelling is how she lived, wrestled, and wrote through the early years of our inherited intellectual moment. Holladay records specific arguments Rich got into with her friend Audre Lorde, and talks a little here and there about difficulties Rich had with various feminist and lesbian magazines, but one ends the book wishing for more of a cultural history of Rich’s thought and perhaps a more in-depth tracing of how Rich’s thoughts expanded, contracted, and became tangential to themselves. And for that, the best source may ultimately be Rich herself.

These biographies do helpful work and I’d gladly recommend them to a reader who has made it through Plath or Rich’s work and wants more. Clark brushes clear the rumor-mongering around Plath and makes an argument for the work, and Holladay provides a stable entry point into the thrust and complications of Rich’s life and thought. As when they met each other in 1958, Plath and Rich still fight to be perceived as legitimate artists rather than smiling, passive representations of the culture they rebelled against.

Devin King is the poetry editor for the Green Lantern Press and the author of The Grand Complication and There Three, both from Kenning Editions. He lives in Santa Fe.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig