by Killian Quigley

Published by Litmus Press and Brick Books, 2010 ; 2010 | 73 ; 104 pages

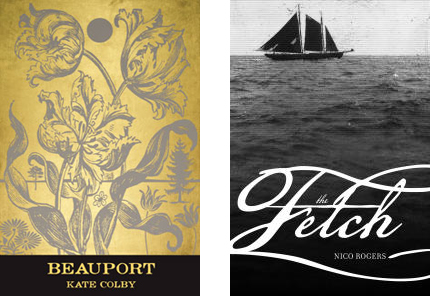

Michael Benedikt, editor of the 1976 anthology, The Prose Poem, claims that “many Anglo-American critics continue, most peculiarly, to regard the prose poem itself as an oblique tributary of the mainstream of modern poetry.” Peculiar indeed, considering the esteem with which poets as venerable as Wordsworth, Baudelaire, and Gertrude Stein held the genre. The prose poem should serve as an ideal entry point for readers eager to experience poetry but put off by conventionally lineated work. Two recent collections — Beauport by Kate Colby and The Fetch by Nico Rogers — attest to the potential of this evolving and innovative form. Through the contemporary prose poem, they re-imagine and retell the lives of inhabitants of territories and cultures long since gone.

Beauport is not the first work in which Kate Colby fuses personal lyric with her retellings of historical figures. Fruitlands, her first collection and winner of the 2007 Norma Farber Book Award, recasts the life of Jane Bowles — a 20th century American playwright and author of the novel Two Serious Ladies — alongside Colby’s own personal experiences. Beauport, Colby’s third collection — a mix of untitled prose poems and titled, lineated lyrics that blend seamlessly — centers on the colorful (but real-life) character Henry Davis Sleeper, a nationally known antiquarian and decorator from Gloucester, Massachusetts. According to Colby, Sleeper built “Beauport” to decorate it and to store his collections, working on it continuously from 1907 until his death in 1934 (it now functions as a museum). In the untitled opening prose poem, Colby depicts Sleeper’s childhood in narrative third-person, utilizing vivid imagery to suggest the child’s (and perhaps Colby’s own) early fascination with color, shape, and texture: “The tonal brown bands of a fuzzy caterpillar. He is taken with tactility, the quiet of it, the immediacy, while behind him, his childhood is spreading.”

In portraying Sleeper, Colby depicts late 19th / early 20th century life in Massachusetts. More specifically, she addresses the upper class’s fascination with early-American, “oriental,” and European influences. In “Fashionable Turn-Outs in Central Park,” the speaker speculates:

<

Strong end-rhyme provides the light and airy feeling of the “plein-air affairs,” as the wealthy take their ritual Sunday carriage rides in the park, while short-lined imagery (“upper-lip-shaped lisping” and “tailcoats”) conveys the affected airs of the rich. All the while the restlessness of the lower classes, with their pamphlets and demonstrations, lingers in the air.Those were the days. Don’t you think?Sunday driving in plein-air affairs of holdrims and spokes,upper-lip-shapedlisping, bespoketailcoats.No incendiary pamphleteersHere, no lady lecturers,temperance hoo-hah

The speaker frequently seems to refer to research Colby did about the period, momentarily rupturing the dramatic effect of the work’s overall narrative style: in “Home to Thanksgiving (1867),” the narrator pens letters to the nineteenth century, calling it “my demented pen pal / my sotted nineteenth century.” Indeed, Colby’s own life in Gloucester exerts a powerful and obvious influence in the book. Writing of California, her thoughts return to the Gloucester of her New England childhood, vividly describing how “the sky presses down on you, the humidity inward, the walls.” Elsewhere, she describes Gloucester’s “temperature regions” as “not a continuum, but a series of seasons, of scenes taking place in a once and future time.” In these reveries, Colby’s language at times rises to lyrical heights, as when, at a family picnic in Gloucester, the speaker claims: “How the sound of rain is composite, composed / of tens of thousands of tiny sounds that are / individually indiscernible.” Time here has become irrelevant, the speaker unable to pin it down, as past lives merge with present ones (Sleeper’s with her own), both strange and unknown.

Just as Beauport does, Nico Roger’s debut collection engages with issues of cultural legacy and inheritance, though The Fetch eschews the complicated framework of Beauport. A Canadian storyteller and performance artist, Rogers constructs The Fetch as series of vignettes told in prose poems. He captures skillfully the lives of those who, in the early and mid 20th century, lived in the harsh landscape and climate of the Newfoundland Islands. Again, as with Colby, Rogers draws from historical documentation — and conducted extensive interviews with the last few surviving islanders — to infuse a culture now lost with fresh life.

Here archival and family photographs accompany poems that shift among first, second, and third-person narrators. These narrators range from a young father watches his child’s birth, a girl desperately seeking attention from her mother, to an elderly couple eating the last of their winter store. Hunger permeates the collection. A child begs God for food in “Praying to Boulders for Berries,” as he bloodies his knees praying outside while foraging, recounting his mother’s perseverance:

Mother would get six dollars a month for dole. She and three other widows from the island would row to Greenspond. Five miles, each way. Never with the help of a man. At no time can six dollars a month keep a person clear of hunger, especially not a family of four. In those years, it seemed like every house had to set an extra plate at the table for starvation.The boy then describes his mother’s “vacant eyes” as he lays beside her by the stove, where they sleep for warmth and comfort.

While many poems tell of hardship and devastation, some evoke longing and love in this bleak landscape. A teenage girl silently addresses her crush in “Stage:” “You were coming towards me, staring at me as I looked into the water of the tub. You were wondering if I was catching glimpses of my smiling face floating with the bubbles.” Loves remains unrequited here: in “Into the Light,” a young man dreams of a beautiful woman he knows with “eyes as blue as the inside of thick ice” and lips as “red and fat as apples.” Elsewhere lovers cling to love lost, such as the widow in “The Man in the Parlour,” who, in a world where men often do not return from sea voyages, clings tightly to the memories that remain: we read that she “…does not remember the marriage with her second husband that lasted three times longer than the first. She only remembers the one who got inside her heart.”

These poems, while fictionalized, serve not only as memorials for the dead but also as informative histories of the time and place. A fascinating glimpse into a departed world, The Fetch’s clear and lyric narrative at times achieves a hauntingness of grandeur.

Alyse Bensel is currently pursuing her MFA in poetry at Penn State. When not engaged in her teaching and studies, she works at non-profit art organizations and at the local CSA. Her poetry has appeared in The Meadowland Review, and her book reviews have appeared in Newpages, Coldfront, CALYX, and on WPSU radio.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig