by by Margaret Kolb

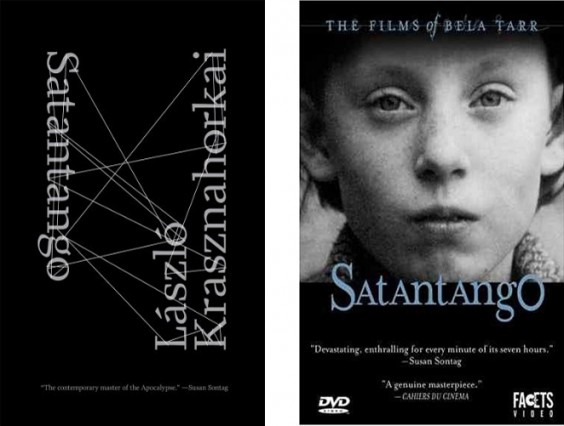

Published by New Directions; Mozgókép Innovációs Társulás és Alapítvány, 2012 ; 1994 | 450 minutes ; 320 pages

I.

“Insofar as the word ‘knowledge’ has any meaning,” wrote Nietzsche, “the world is knowable; but it is interpretable otherwise, it has no meaning behind it, but countless meanings.” What Nietzsche called “perspectivism” was an epistemological skepticism that suggested there were no facts of permanence, only interpretations, senses of fact, phases of fact. Knowledge as such was either too specific or too vague, but always fragmented, the incomplete shard of a greater, inaccessible prism of meaning. Perspectivism is memorably echoed in Henry James’ “house of fiction” analogy (in his famous preface to The Portrait of a Lady), at each of whose windows “stands a figure with a pair of eyes, or at least with a field-glass, which forms, again and again, for observation, a unique instrument, insuring to the person making use of it an impression distinct from every other. He and his neighbours are watching the same show, but one seeing more where the other sees less, one seeing black where the other sees white, one seeing big where the other sees small, one seeing coarse where the other sees fine.”

Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s Satantango, first published in 1985 and only recently translated into English from the original Hungarian, is a “house of fiction” whose perspectivism motors its incidents forward toward an entropy that paradoxically (and perpetually) reverses and restarts in cycles of repetition. The structure of the novel reflects this. The first six chapters progress forward (numbered I-VI), and the latter six regress backward (numbered VI-I)--deriving their theoretic energy from the title itself, a satanic tango that moves six motions forward, only to revert six steps back, outlining an eternal recurrence that repeats, forward and back, and forward and back again, an apocalyptic progression that proceeds without ever progressing. The effect is one of an inertia-induced vertigo. Eternal recurrence is, of course, a central idea in the writings of Nietzsche. Krasznahorkai even titles two of the novel’s chapters “The Perspective, as Seen from the Front” and “The Perspective, as Seen from the Back”—titles which come to signify not necessarily a repetition of the same, but a divagation from that sameness (the sameness of facticity), an interpretative dance of irregular drunken bodies tuned to the melody of a czardas.

Satantango begins declarative yet dreamlike: “One morning near the end of October not long before the first drops of the mercilessly long autumn rains began to fall on the cracked and saline soil on the western side of the estate (later the stinking yellow sea of mud would render footpaths impassable and put the town too beyond reach) Futaki woke to hear bells.” Krasznahorkai’s characteristic “long-take” sentences, which pile multiple clauses on each other, often delay or disguise the central declarative fact. In this case, it is a fairly straightforward declarative statement (“One morning...Futaki woke to hear bells”) interrupted by other conditional and conditioning events (“autumn rains,” “cracked and saline soil,” “stinking yellow sea of mud”) which render, figuratively speaking, the grammatical and cognitive “footpaths impassable” and the predicate “beyond reach.” We learn that Futaki may or may not have heard bells – he only sensed he had, but the initial fact (he woke to hear bells) is contradicted by other conflicting facts (“the closest possible source was a lonely chapel…that not [only did not] have a bell [but] was too far to hear anything”). Futaki soon doubts his initial apprehension: “...there was nothing to hear however hard he listened but the dull beating of his own heart...” Fact recedes into interpretation, itself “a brilliant conjuring trick to produce something apparently orderly out of chaos, to establish a vantage point from which chance might begin to look like necessity….”

Indeed, the possibility of “establishing a vantage point,” a small place from which one can look out into a dreary world and invent myths about what goes on in the outside, is all that is left to the inhabitants of the dilapidated, half-abandoned village Futaki wakes up in, the remnant of a communist collective farm on the verge of implosion. The landscape that greets him that morning is one “riddled with serpentine channels” and fields choking with rain. The corrosion of Goulash Communism has left streaks of apocalyptic rust in everything. Futaki, an introspective cripple who wanders from town to town in search of work, is only one member of the few remaining people who live in the village. The Schmidts, the Kraners, the Halics, and the Horgos family share the space of the derelict village with a “landlord” who tends the local bar; with Kerekes, a local farmer who spends his hours drinking at the bar; and with an obese, alcoholic doctor, also nameless (hardly anyone goes by first name here), who lives apart from the others in a brandy (pálinka)-drenched solipsism, as he, in a kind of parody of communist informant networks, sits at his window and meticulously transcribes village events in journals categorized by the names of the villagers. Often nothing happens outside the doctor’s window, and the nothingness itself becomes the subject of the doctor’s gaze, which extracts from insignificant motions and nonevents occult significations:

“However apparently insignificant the event, whether it be the ring of tobacco ash surrounding the table, the direction from which the wild geese first appeared, or a series of seemingly meaningless human movements, he [the doctor] couldn’t afford to take his eyes off it and must note it all down, since only by doing so could he hope not to vanish one day and fall a silent captive to the infernal arrangement whereby the world decomposes but is at the same time constantly in the process of self-construction. It was not, however, enough to remember things conscientiously: that ‘was insufficient in itself,’ not up to the task: one had to compile and comprehend such signs as still remained in order to discover the means whereby the perfectly maintained memory’s sphere of influence might be extended and sustained over a period. The best course then, thought the doctor during his visit to the mill, would be ‘to reduce to a minimum such events as would tend to increase the number of things I have to keep an eye on...’” (55)

The reduction of events in Satantango paradoxically increases the number of things the reader has to keep an eye on—paradoxical because what little there is of plot-narrative in the novel perforce enhances the wider psychological web Krasznahorkai weaves around the intertwined lives of the villagers.

The principal narrative can be summarized as such: two men once believed to be dead, Irimiás and Petrina (whose inseparability and roguishness seem to evoke a latter-day Quijote and Sancho, respectively), are spotted on the road returning to the village. The lethargic villagers (Futaki among them) are jolted by the prospect of two “resurrected” men returning after a two-year absence, ostensibly to save them from the poverty and despair of their mundane existence. Indeed, Irimiás in particular is perceived by most of the villagers to be a kind of savior, an ambitious man who had, previous to his falsely announced death, brought some measure of economic life and industrial guile to the village. But the “factual” truth is quite different: we learn gradually (or, rather, we are drawn to make the conclusion) that Irimiás and Petrina had functioned as communist informers in their village, had somehow committed a crime (the nature of the crime is never made clear) which led to a two year prison term, during which time the rumor of their death had spread in the village. Newly released from prison, Irimiás and Petrina have returned to the village with a tentative plan to embezzle what remaining lucre the villagers may have stored away.

While the villagers await the imminent arrival of Irimiás and Petrina to the village pub (where we learn of the alarmingly differentiated, yet frequently bleak, thoughts that define the mental life of each villager), little Esti Horgos, the youngest and most neglected daughter of the Horgos family, commits suicide. Irimiás and Petrina, who somehow chance upon Esti’s body, cynically use the occasion of Esti’s death to collect the bulk of the village trust fund and invest a portion of it for her burial; but they also suggest a nebulous plan to leave behind the village and install each villager in different “jobs” in metropolitan areas, the real purpose of which is “the unceasing, vigilant observation of their immediate surroundings” and “all opinions, rumors, and events” that would raise suspicion or entice state interest. Believing Irimiás’s every word, the villagers agree to the plan (not without spending the night prior bickering and fighting about whether Irimiás would dupe them again), and by the end of the novel, what had been a collective unit that spent its time spying on itself in a close-knit circuit disintegrates (or, rather, reintegrates) into a dispersed body that spies on others within a larger communist Hungary on the brink of rupture and modernization.

The landlord (who despises Irimiás and resents the others’ abuse of credit at his bar) and the Horgos family (except the son Sanyi, who chases after his idol Irimiás) are left behind, but it is the bumbling, misanthropic doctor with whom the novel closes. The doctor had, the very day of the village exodus, fatigued and in poor health, blacked out on the road while seeking to refill his jug with more pálinka to fuel his panopticist “research”. Returning to his home after a prolonged stay in the hospital, the doctor continues to gaze out of his window and write reports on the smallest incidents in the village, unaware all the while that the villagers had weeks earlier left the estate with Irimiás. By this point the reduction of events under his purview has reached a nihilism so profound (“no movement anywhere”) that the doctor eventually decides to board up his door (to remain undisturbed) and write his own versions of the (non)events that he imagines are happening within the vacant homes of the observed. Inspired by the inverse freedom of the boarded-up door and the fresh supply of pálinka, cigarettes, and medication “that will last till spring at least,” the doctor begins to write a fiction (to make up for the lack of movement or notable event outside) of which the very first sentence is precisely the one with which the novel begins: “One morning near the end of October not long before the first drops of the mercilessly long autumn rains began to fall on the cracked and saline soil on the western side of the estate…Futaki woke to hear bells.” We know how the story goes. The “circle closes” yet the satanic loop begins anew; the repetition with which the novel ends redefines the chronologic events that came before. What had been posed as a factual instance at the beginning of the novel (“…Futaki woke to hear bells”) – a fact upon which the entire thread of the novel’s events was woven together to produce a spider’s web of involutions and detections, characterizations and actions – turns out to have been an interpretation surrounding the absence of a fact, a vacancy posing as a presence, a hallucinated script issued from the skewed perspective of a slightly mad doctor drunk on pálinka.

The doctor only appears in two chapters of the novel (the third and last), but they are (aside from the chapter in which Esti makes her appearance in the first person) perhaps the most revelatory, and certainly the most overtly perspectivist. Sitting at his armchair facing the window, pálinka in hand, cigarettes and tinned food in store, hardly ever rising except to relieve himself at the toilet “whose cistern had not worked for years,” the doctor arrives at a new definition of order, one in which the more he ignored the eventual decay and erosion of things, “the more attention and expertise he devoted to maintaining the order around him—the food, the cutlery, the cigarettes, the matches and the book—all with the correct distance between them on the table, the windowsill, the area around the armchair and the fiercely aggressive rot on the already ruined floorboards…” Here disorder posits the beginning of a higher, abstruse form of order, one which relies on the autonomy of still objects to arrange themselves and be consumed by processes of decay. The doctor’s cosmic drama, it is revealed, hides the kernel of what went wrong at the estate:

“So, doing nothing, he simply remained on the alert, careful to preserve his failing memory against the decay that consumed everything around him, much as he had done from the moment that he…had gone up to the mill with the elder Horgos girl to observe the terrible racket of the abandonment of the place…when it seemed to him that the mill’s death sentence had brought the whole estate to a condition of near collapse…” (54)

Traumatized, it seems, by the financial collapse of the mill and the resultant closing of the estate, the doctor decides to stay behind and “survive on what remained until ‘the decision to reverse the closure should be taken,’” a closure that he reverses paradoxically by writing the opening lines of a notebook that the reader, ahead of him, has already read.

The multiple perspectives that make up Krasznahorkai’s novel, which flow imperceptibly from one character to the next without marker or interruption, thus turn out to be the fabrication of a single perspective that is itself confined to the filthy recess of an outlying home whose corridor is lined with weeds, whose doorstep serves as a trash depository, and whose stench is so strong that Mrs. Kraner refuses one day to continue cleaning it (“‘I tell you, that smell is unbearable, simply unbearable…’”). Which is not to rule out that what we have read, from the pages taken out of the notebook of a decrepit doctor, contains “facts,” but rather to reaffirm that the facts of existence metastasize into tumorous agglomerations of competing visions, of perspectives that dimly illuminate the edges of an unavoidably dark, darkening truth.

Comprehending this, the doctor’s gaze seeks in nonevents and stationary objects the secret to the machinations of an occult “chaosmos” (to borrow a phrase from Heriberto Yépez), a cosmos whose order eludes structural analysis, whose organizational principle is precisely the absence of one. In Krasznahorkai’s house of fiction, facts work, futilely, numbly, like numbers, to restore faith in things—“because there is in numbers a mysterious evidentiary quality, a stupidly undervalued ‘grave simplicity’ and, as a product of the tension between these two ideas a spine-tingling concept might arise, one that proclaimed: ‘Perspectives do exist.’”

II.

George Szirtes’ translation of Satantango, itself a miracle of form, is the first English language translation of Krasznahorkai’s novel. But Satantango had already been available as a translation (we may call it a transmediation) for years in the form of Bela Tarr’s celebrated film adaptation Satantango (1994). It may be fair to claim that Bela Tarr’s filmography, distinctive and overwhelming on its own, largely introduced an international audience to the work of Krasznahorkai. Tarr and Krasznahorkai had first worked on Damnation (1988), a film which represents both the beginning of their collaboration and the formalist break with Tarr’s earlier social realist works of Hungarian modern life. Besides Satantango, Tarr’s films after Damnation (Werckmeister Harmonies [2000]; The Man from London [2007]; The Turin Horse [2011]) would permanently define what came to be known as the Tarr aesthetic, one which showcased many of the key features of the so-called “slow cinema” movement, namely slow-burn long takes, minimalist set design or natural landscape, ambient or purely diegetic soundscapes, and minimal, sometimes absent, dialogue. (Tarr is renowned for his long take precisely as Krasznahorkai is for his long sentence). Tarr’s “slow” practice, in his own words, eschewed the “information-cut” aesthetics of conventional cinema and brought the film viewer to engage more directly with the actual organic processes of life itself than with the artificed informatics of overly filmic scenography. Tarr’s attitude toward his artform is surprisingly close to Krasznahorkai’s: “For us, the story is the secondary thing. The main thing is always how you can touch the people? How can you go closer to real life? […] We don’t know, for instance, what is happening under the table, but there are interesting, important and serious things happening.” [Quoted from Kinoeye interview with Phil Ballard]. For Tarr and Krasznahorkai there is nothing, however minute or static, that is undeserving of the human gaze.

Tarr’s Satantango is famous for both the stark poetry of its images and the massiveness of its length: the film clocks in at 432 minutes, exactly 7.2 hours. Adapted for the screen by Tarr in collaboration with Krasznahorkai himself, the length of the film roughly coincides with the literal reading time of the novel. For instance, to test the plausibility of this hypothesis, I timed myself reading aloud the first chapter of Krasznahorkai’s novel, while leaving the film to play in the background, volume off, and discovered that it took me approximately 32 minutes to read through the initial 20 pages, almost the same amount of time that the correspondent first section of the film—“I. News of their Coming”—took to play through. The same could be said of the rest of the chapters and their respective translations into filmic space: Satantango’s 7.2 hour length approximates to the amount of time a neat and adequately processed live reading of the novel would take. The two Satantangos are in some facets comparable, but in others they are different – they coexist in a necessary tension, a tangible differentiation that presents two perspectives to the same core work.

Perspectivism remains a key element in Tarr’s adaptation, so much so that certain parts in the film can be argued to illustrate some of the novel’s themes more efficiently than in Krasznahorkai’s original. Front and back perspectives are taken quite literally in their cinematic telling. For example, the scene in which the villagers leave the estate for the last time, and are instructed by Irimiás to rest and reconvene at nearby Almassy Manor, occurs twice in the film, with the camera shooting it once from the “front” and again from the “back.” Tarr repeats this gesture in various other scenes as well. The question of book space versus film space emerges here (by which I mean the time of immersion within the specific medial and spatial parameters of a work). In both aesthetic zones, the act of watching is itself the subject of watching. Krasznahorkai’s long sentence is approximated by Tarr’s long take. Take for instance the following moment in the novel:

"He [the doctor] jerked his head up and listened intently to the silence, then the matchbox caught his attention because, just for a moment, he had a decided feeling that it was about to slip off the cigarette pack. He watched it and held his breath. But nothing happened." (263)

This is precisely what Tarr accomplishes with his long takes: he captures the nothingness with which life fills up the screen, the tension that infuses objects with a possibility of emotion. It is the act of gazing, the pure gaze, that the gaze itself seeks, and, in seeking, strives to frame, to let flow. In both Satantangos, the gaze occasions the bifurcation of reality into truths and untruths, events and hallucinations, movement and stillness.

In Krasznahorkai’s novel, shortly after the suicide of little Esti (she drinks rat poison in a moment of angelic epiphany, or so she verbalizes it to herself), Irimiás, Petrina, and Sanyi encounter what seems to be a “heavenly vision”: “To the right of them above the marshy lifeless ground, a white transparent veil was billowing in a particularly dignified fashion.” The veil, which Esti treasured and had worn when she died, touches the ground and suddenly vanishes—startling the three into a religious stupor. They scramble, but eventually encounter “in front of three enormous naked oaks, in a clearing, wrapped in a series of transparent veils…a small body,” the body belonging to Esti, whom they had just buried only a few hours ago. They hear a “sweet, bell-like laughter everywhere” and it is only when they have left the site that they start nervously reasoning that it was only a “hallucination” incurred by fog and wind. Irimiás is most adamant: “‘It doesn’t matter what we saw just now, it still means nothing. Heaven? Hell? The afterlife? All nonsense. Just a waste of time. The imagination never stops working but we’re not one jot nearer the truth.’” Tarr’s adaptation forgoes the vividness and panic with which Krasznahorkai invests the scene; instead, we see only fog passing by the woods on a drizzly afternoon (no saintly corpse, no floating veil). Tarr’s long take of a clearing, of fog passing through, then vanishing, allows us to see an ordinary occurrence as an instance of occult intentionality—the long take rewards the lengthened gaze, the normally stationary table moves, the wine glass vibrates, the fog passes itself off as a sacred veil that floats and dashes away. Film space and book space differ in the perspectives given for a single event; but they coincide in the transmedial solidity of the thematic ramifications of the same event. In both the novel and the film, perspectivism posits the singularity of difference; it is difference that repeats the same even as it makes it new.

There is one last, seemingly minor, yet pivotal, difference between the novel and the film adaptation. When the doctor boards up his house to write the fiction that is to become Satantango, he does not board up the door so that “no one would disturb him” but boards up the window. This small change is major because it accentuates the major differences between film space and book space: in the latter, Krasznahorkai can explain away the dialogic or verbal reasoning behind the doctor’s boarding up the door, so that we don’t have to see the effect, we only mentalize it in the doctor’s oralized mind; however, in film space, such a gesture does not impact the viewer as strikingly as that of the doctor boarding up the window and resultantly darkening the screen, leaving us in total blackness (an entropic gesture that Krasznahorkai and Tarr would repeat for the conclusion of The Turin Horse).

Why then does the doctor board up the window in Tarr’s retelling? Ultimately, there appears to be only one true fact of the story, for both the novel and the film: there is a madman in an abandoned chapel ringing the bell. This is what Futaki, woken up at the beginning of the novel, hears—and what the doctor, at the end of the novel, investigates and discovers (the doctor hears the same bells Futaki heard and goes out to discover that there is an escaped lunatic hiding in a chapel who, from time to time, rings the bell). Faced with the indecipherability of this maddeningly singular fact, the doctor returns home, boards up his windows, and begins to write fictions that will pass as facts. The reader is thus led to the assumption that this “fact” elicited the composition of the text she is reading. “One morning…” etc. Which is to acknowledge that facts are meaningless unless they are given over to interpretation. One can’t say or do much about a madman who rings a bell in an abandoned church. It just is. This absurd fact, in all its unassailable isolation, cancels out even the doctor’s “perspective”: he boards up his window to the world because his perspective (a window shrouded in mud and streaked with rain) is literally and symbolically opaque, useless, terminally obscure.

In the end a single fact obliterates even the perspectives that surround it: a madman rings the bell in an abandoned church. This fact is hidden within the final moment of the story, so that the play of perspectives can begin again around such a (disturbing) fact that insists upon interpretative measures. What do Krasznahorkai/Tarr confirm with their fable? That the author writes in the dark (God writes in the dark). We understand this even more directly in the film translation: after boarding up the windows, the doctor begins to write in the dark. We cannot see him, nor anything else, only his voice emerges from the darkness, reciting the first lines of the novel, the original lines in Hungarian, written by Krasznahorkai and transposed to the screen (ironically, a screen of blackness) by Tarr. And we are struck with the bold truth of the scene: the author writes in the dark – she creates, invents, fictionalizes, outside of both fact and perspective. The specificity of the window-door correlation, in their respective aesthetic spaces, is maddening. “Perspectivism,” as Nietzsche would have it, “is only a complex form of specificity.”

Jose-Luis Moctezuma is a current doctoral student at the University of Chicago. His studies focus on technologies of the image in poetry, cinema, and literature. His work has been/will be published by Berkeley Poetry Review, PALABRA, and Cerise Press.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig