by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Riverhead Books, Catapult , 2021, 2021 | 224 pages, 272 pages pages

Will the Internet break the novel? Or, more precisely, what will social media do to our most socially rooted literary form? The novel took shape alongside newspapers and the public sphere, eighteenth-century advances now rapidly disintegrating into polarized tidbits in service of social media algorithms. Novels depend on our ability to care deeply about people we have never met, inviting us into the minds of murderers and adulterers, child abusers and money lenders, encapsulating myriad voices and points of view, without final adjudication among them. But today, when our daily engagement with others routinely presumes either identification or opposition, embracing empathy for strangers and valuing unresolved difference seems downright antediluvian. If life online has sent friendships, journalism, and politics reeling, how will it affect the fundamental values of the novel? And if those values are on the move, where are they headed, and will the genre survive?

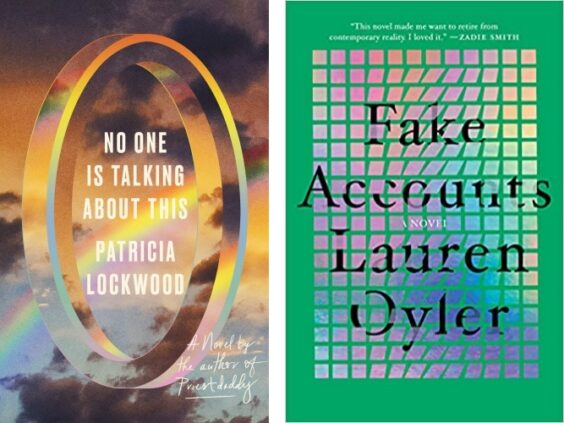

Where better to think through these questions—or at least frame them—than in a novel? Two debut novels of 2021, Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts and Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, ask what it means to write a novel in a Trumpist world. Both writers are smart, young, and very much online. Oyler’s cultural criticism enjoys a broad reach; her prominent slam of Jia Tolentino’s memoir Trick Mirror (2019) sent shockwaves around Twitter. Lockwood, whose incandescent memoir Priestdaddy (2017) chronicles her improbable writerly journey, has managed to dive to the bottom of the Internet and emerge spouting diamonds, rather than the toxic bilge one might expect. An early Twitter adopter, her cryptically comic tweets remain recognizable—albeit distant—cousins to the luminous prose she now also contributes to the London Review of Books.

Both writers set their novels in the Trump presidency (though Lockwood dubs him only “the dictator”). They share the agonizing burden of holding readerly attention against the backdrop of our recent past, with its schizophrenic shifts in mood, attention, and priorities. The burden shows; the burden becomes, in many ways, the point. Both novels can be said to have a plot—the narrative demand in greatest tension with the Internet—but these plots remain minimal. Fake Accounts chronicles a breakup and its aftermath, both determined by social media. When Oyler’s (nameless) narrator sneaks into her boyfriend Felix’s phone, she realizes that Felix is an online conspiracy theorist, despite his evident lack of belief in such theories. Before she can break up with him, Felix dies, and Oyler’s narrator grieves first by heading to the Women’s March, and then by moving to Berlin and launching a series of fake dating accounts. Fake Accounts chronicles the narrator’s grieving process, and the series of in-person meetings that arise from her strategic profiles, posts, and searches.

No One is Talking About This, by contrast, consists of a series of barely constellated moments, the close-third person musings of an (also nameless) Internet savant who, like Lockwood, rose to prominence through memorable misuse of the English language on what Lockwood calls “the portal.” Her earliest hit (“Can a dog be twins?”) has gone viral. Its inexplicable stickiness in the collective consciousness propels her around the globe to opine on Internet trends for live audiences, even as the emergence of the dictator explodes the very context in which “Can a dog be twins?” might be influential, important, or even memorable. The narrator of No One Is Talking About This remains immersed in this comically upended “portal” until the novel is a third underway, when a crisis with her sister’s pregnancy looms so large it begins to supersede even the Internet. Whereas Oyler examines how the worlds we build online shape our lived encounters, Lockwood asks what forces might be strong enough to wrest us offline.

These plots are not complex, and when complications arise, they are eminently foreseeable. We turn the page not to find out what happens next in the portal or on Tinder, but instead to witness what will happen to the writing. The Internet has overtaken us, both novels declare, and both novels want to know: how will we write about it? Lockwood’s barely connected fragments bear witness to the disintegration of language, logic, and connection under the various pressures of life online. “Some people were very excited to care about Russia again,” Lockwood’s narrator writes of Russian election interference. “Others were not going to do it no matter what. Because above all else, the Cold War had been embarrassing.” Like this one, the novel’s fragments are playful, endlessly generable, and bend language just enough to stick. Mercifully, they are also short.

Fragments continue throughout the narrator’s sister’s pregnancy, though they are increasingly grounded in hospital, rather than portal, screens. Once Lockwood’s sister delivers and the family encamps in the NICU, the last third of the novel transforms into an agony of fragments constellated by the baby, who knits the narrative together with the shock and joy of her all too fleeting presence. “What did a story mean to the baby? It meant a soft voice, reassurance that everything outside her still went on, still would go on,” the narrator wonders, her idle musings gathering with her intense effort to know and understand another mind. Lockwood’s most lasting turn of phrase occurs in her acknowledgement of her niece Lena “you did not come to teach us, but we did learn,” and her dedication “to Lena, who was a bell.” Clarity, for Lockwood, is partial and fragmentary, earned only through sporadic thoughts that pain gathers together to give the novel, almost two thirds finished, a heartbeat. When the clear prose of the novel’s final section arrives, it rings like a bell: painful, sweet, and throbbing.

Oyler, by contrast, writes page-long paragraphs which reflect the shallow, but very much connected musings of an intelligent young woman tasked with producing reams of cultural content online. These lengthy paragraphs are comprised of sentences that, while finite and grammatical, manage to feel well-nigh endless. A typical sentence reads:

Knowing what happens next (you’re about to find out), and how he ended up performing as a boyfriend (you know some of this and will learn more), and what happens after that (this would be the conspiracy-theory thing, which you also know), and what happens that (truly unbelievable, though in some ways not; you do not know this yet, unless you’re one of the people I’ve discussed it with), I would like to deny that I liked him very much by this point.Oof. Oyler’s narrator maintains this style unabated throughout, as if she were writing one long, extraordinarily peppy text message, crafted to emphasize her own intelligence and the chatty spontaneity of her musings.

Whether fragmentary or voluminous, both novels are engrossing—often engrossingly trashy—much like life in the pre-pandemic Trump presidency, if anyone can now remember back that far. They are also strange, in ways that might prove predictive of the future of the genre. Both are deeply committed to recording recent history with an accuracy that turns the Internet into something of an archive for readers. It is possible, for example, to look up Twitter handles directly from Oyler’s novel. Lockwood’s portal and dictator track our own so exactly—right down to the trashy Buzzfeed article about Gone with the Wind, accessible online—that her need to defamiliarize this world through haphazard disguise is striking. It is as if our world has become so excessively novelistic that the task of the historical novel might be to allegorize it by erecting a partial veil: dictator, portal. As if feeble artifice (Lockwood’s renaming; Oyler’s chatty asides) might afford some semblance of escape.

The novels are even stranger in their profound lack of interest in the characters they represent. Whereas Lockwood’s memoir Priestdaddy brims with developed, novelistic characters speaking in loud, bright voices, her debut novel empties all voices save her narrator’s—this despite the fact that characters and situations in the novel are recognizably members of Lockwood’s family, acknowledged in the book, as well as in interviews. This limitation is somewhat puzzling, given that the novel sets up important and deeply American disputes, from abortion rights to medical bureaucracy (both treated with serious consideration of myriad points of view in Lockwood’s memoir). In No One is Talking About This, we watch the narrator’s pro-life father swallow upon discovering that there are not legal medical exceptions in his daughter’s case, despite significant risk to her life. But we scarcely hear him, or his expectant daughter, or that daughter’s partner, speak. In Fake Accounts, Felix (the conspiracy-theorist boyfriend), remains similarly unvoiced; Oyler’s narrator devotes endless pages to her own impulses and interests, but exhibits more interest in her boyfriend’s phone than in him, and Oyler affords him no escape past her myopic narrator. Internet writing, both novels seem to say, nudges writers to filter out every voice from every experience, save their own.

No One Is Talking About This and Fake Accounts are significant achievements for their writers. But if they are signposts for where the novel is headed—and they just might be—they do not bode well for the form. Both write with Dostoevskyan insight into the human psyche—that is, if Dosteovsky were an atheist, restricted to tweets and texts. Their staggering insight and craft warps at the size of the piddling questions they get stuck asking (should Lockwood’s narrator post a photo of the baby on the portal? How should Oyler’s feminist narrator understand her desire to make her boyfriend pancakes for breakfast?). Readers who do not wish to greet these Internet novels as the one true future can take heart by turning to Sally Rooney (her latest novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You (2021), begins on Tinder, but concludes with a dog barking at a television). At any rate, take respite where you can. Oyler and Lockwood are some of the most intelligent writers alive, and their novels are bleak harbingers for where the American novel might be headed.

Margaret Kolb got her PhD in English literature from UC Berkeley, where she now teaches. Her writing can be found in Victorian Studies and Configurations, as well as in the Palgrave Handbook of Literature and Mathematics. She is working on a book analyzing cultures of prediction, both literary and mathematical.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig