by Killian Quigley

Published by Sarabande Books, 2011 | 37 pages

What do we think of when we pass cows grazing out along the highway, if we think anything of them at all? Perhaps we think there is something incomprehensibly dull about them—or stubbornly languid. They are fixtures of the landscape become that landscape. Their nearly inanimate bodies seem like bales of hay or rocks or trees; their consciousnesses may seem as removed. They are, as Lydia Davis reveals in The Cows, unknowable others onto which we project so much that is human. And yet, Davis asks: are we not, ourselves, unknowable others? Do we not, as the cows seem to, inhabit our own selves just as mysteriously, if perhaps somewhat less completely?

There is something lovable about these cows—the seeming slowness of their processes, those thick eyelashes. We regard them as benign creatures, as unwitting comedians. Davis acknowledges the comedy inherent in these three. The slim volume unfolds at a pace which could be described as bovine: “They come out from behind the barn as though something is going to happen, and then nothing happens.” They begin the day in one part of the field and somehow, later, wind up in a different spot: “So often they are standing completely still. Yet when I look up again a few minutes later, they are in another place, again standing completely still.”

Davis is well known as a writer of poetry and short fiction, and also as a translator of French writers such as Proust and Flaubert. She intuitively understands the silent gravity of gesture, the subtle revelations of the observer and the transformative power of subjectivity. Indeed, her work in The Cows seems like a kind of translation, one that is respectful of the differences between animal and human subjects. Through this act of translation, Davis reveals much about her animal subjects and, inevitably, herself.

With The Cows, Davis enters the literary tradition of landscape art. As in that tradition, Davis’s art is a negotiation, one that strives to both represent the landscape (in this case, the cows) in their own right, but also simultaneously utilize them - those mysterious shadow-puppets – to better explore human consciousness and relations (fables are perhaps the quintessential manifestation of this latter tendency). Davis never presumes to give us a truly objective view of cowhood, but does mange to present a respectful and subjectively honest account of what she sees. Through the daily act of looking, and her patient observation of individual behaviors, she gives us the cows as they appear to her to be to themselves, with a minimum of anthropomorphization. Consider: “The third comes out into the field from behind the barn when the other two have already chosen their spots, quite far apart. She can choose to join either one. She goes deliberately to the one in the far corner. Does she prefer the company of that cow, or does she prefer that corner, or is it more complicated—that that corner seems more appealing because of the presence of that cow?”

It is notable how Davis constructs human identity throughout the book, insofar as no individual human being is ever named or described directly. The most we get of humans, aside from the narrating observer herself, comes in the form of little self-revising statements about the cows, like this: “He says to us: they don’t really do anything. / Then he says: But of course there is not a lot for them to do.” In such moments, we encounter something practically abstract: the reverse silhouette of a person. Our attention is directed toward the cows whose apparent sameness is not challenged explicitly. Instead, their outlines are shaded in gradually, page by page. If a human were to be included in the book, they might function as a kind of magnetic presence that pulls us away from the cows, with whom we identify less. The virtual absence of this comforting human presence (aside from the narrator’s own voice and visuals) gives the cows the chance to occupy our attention more fully.

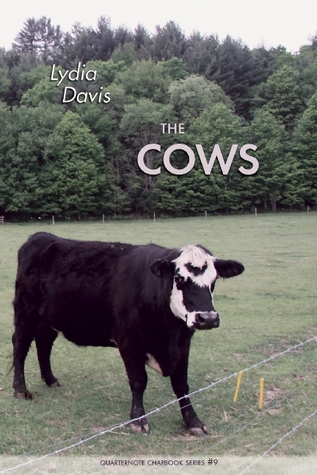

Photographs taken by Davis, Theo Cote and Stephen Davis appear throughout the text, presenting the cows standing about in their enclosure, looking this way, then that. Davis shows us what she has seen from her window day after day: cows… and grass. But as we study these pictures they, too, begin to reveal provocative subtleties of expression and mood. In one picture two cows appear in the foreground, and the ear of the third behind them angles backwards, as if it were listening to something. In the next picture the two closer cows have shifted slightly, and the ear of the cow behind them has been lowered to a more natural position. Near the beginning of the book is perhaps the most wonderful picture of all: a single cow recumbent on the grass with a particularly alert expression on her face. What she sees and hears and perceives is out of the frame, elusive.

Ann Marie Thornburg received her MFA in poetry from the University of Michigan in 2011. Her poetry appears in The Boston Review, and is forthcoming in Michigan Quarterly Review. She is the recipient of a Zell Postgraduate Fellowship for 2011-2012.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig