by Alessandra Stamper

Maggie Nelson is the author of four books of nonfiction, including The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (W. W. Norton & Company, 2012) and Bluets (Wave Books, 2009), as well as four books of poetry. Formally inventive, deeply researched, and uncompromisingly original, her work is both personal and political, its critical reception revealing as much about our culture as the work itself does. For this interview, she spoke with Tim Kinsella − newly minted Featherproof Books editor and author of Let Go and Go On and On (Curbside Splendor, 2014) − about risk, vulnerability as a writer, and the color blue.

Tim Kinsella: How has your relationship to blue changed in the five years since the publication of Bluets? The relationship as you describe it in the book is so extended and ongoing, it would seem like your experience with Blue couldn’t just end, but that the book had to stop being written at some point. Do you remember at the time feeling a sense of closure? Catharsis? Frustration? After holding a specific filter in place and seeing everything through that filter, how are you then changed by its removal?

Maggie Nelson: My relationship to blue has changed pretty much entirely. It’s almost like it’s an ex I don’t speak to anymore. This change has many roots, but I do think it’s a fairly natural effect of burning through something, via intense focus, if not obsession. There was definitely a moment when I had to start turning down people’s blue stories and leads, just so I could marshal what I already had. I remember my friend Christian Hawkey telling me about the blues of Georg Trakl and feeling heartbroken that I couldn’t let them in; the party was closed, the drawbridge was up. Sad as this all has felt, it’s also likely as it should be—more than any book I’ve ever written, Bluets had a dramatic point of closure, a point at which I knew it was finished. I put it in a box and didn’t look at it again for a long time, like maybe a year. It was like I finished a performance and left the stage. But so far as I can tell, when you remove a filter, you just make room for a new one.

TK: When you were younger, before writing your first book, how clearly did you visualize or anticipate your own aesthetic? Was the willingness to occasionally write about yourself in such an intimate way always a given to you? How much of the act of writing is invested in that sort of vulnerability?

MN: Wow, I love that idea—imagining one’s aesthetic before one has developed it! I wasn’t nearly so advanced. Wanting to write, that was enough. Certainly I had heroes, whose sensibilities acted as a guide, even if I was nosing around in the dark. I remember in high school, being given a list of quotes about “the meaning of life” and being asked to choose the one we resonated to the most, and I chose one by someone I’d never heard of, John Cage. Maybe the rest is history. As for writing intimately, I came up in the 80s and 90s with AIDS and ACT UP and radical feminism and my writing heroes were pretty unworried over intimacy and vulnerability—there was too much work to do. They weren’t sitting around worrying over the mores of self-exposure. I’m thinking of people like David Wojnarowicz and Eileen Myles, and before them, James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, you know, people with work to do. Whether or not you got to it through intimacy or scholarship or activism, you just got to it, that was the thing.

TK: How does the form of Bluets—gaps and leaps—relate to that vulnerability? How do you hope the reader will feel the form? How do you hope the reader will think about the emotional content?

MN: You know, I never imagine any reader of my work. I don’t mean this coldly; I like people reading my work, and I like it if they like it. But I can’t worry about anyone else while writing. It has to sound right to me, it has to feel “true,” it has to have a structure that strikes me, upon reading and re-reading, as exactly so. But getting there is more intuitive than mapped out. Vulnerability as a goal strikes me as a little yicky, or at least un-useful. I think vulnerability is just something that happens if you’re truly engaged in stripping away self-deceptions, bravado, ego, and so on, and looking to find what’s most thrumming in one’s self, in the world. I’m interested in how writing can enable that process, not in performing any predetermined set of emotions or values.

TK: Your accomplishments make clear that you must be pretty motivated. I mean there’s a certain base strength necessary to executing one’s will in the world. But you write very openly about some pretty harrowing despair. In a practical sense, how does this play out in terms of your process?

MN: I’ve been blessed with episodes or a sensibility that I would characterize, if push came to shove, as hypomanic, by which I mean that I haven’t suffered—knock on wood—the kind of depression that seriously inhibits writing, except in periods of weeks, maybe sometimes months, rather than years. The Red Parts and Bluets were both written at very hard times for me. I don’t really know how I did it, although in retrospect, it certainly looks a lot like coping.

TK: Is the occasional emotional brutality of Bluets subject in any way to The Art of Cruelty? How did the writing of the one book inform the next one in both conscious ways that you recognized at the time and unconscious ways that you can now see?

MN: Is Bluets emotionally brutal? I’m intrigued. Usually I think of it as something of a break from the cruelty/violence books, which to me are Jane: A Murder, The Red Parts, and The Art of Cruelty. I’ve always been interested in the play between abstraction and figuration, and have sometimes mentally broken my books up into the abstracts (Bluets, Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions), and the concretes (the cruelty books named above). I think it might have been Deleuze, writing on Bacon, who asked: does cruelty depend in some sense on there being a figure? Can there be a “cruelty in the abstract,” as Artaud is always talking about? In this sense, Bluets—along with color in general—acts a kind of a negotiator between the abstract and concrete: color is an abstraction, but it must come into being via specific objects, specific eyes registering specific wavelengths. This may be a roundabout way of answering your question, but maybe, hopefully, you’re following me… The pain in Bluets derives from the urge to link an experience of love or beauty to a specific person or impermanent object. But of course that’s what we do—we don’t just sit around loving the big, abstract, immortal concept of “blue.” Is that cruel? I don’t know. Only as cruel as the first noble truth.

TK: So many sources are woven into your writing, it becomes about a sort of masterful sequencing and balancing. Obviously David Shields’s Reality Hunger or David Markson’s collage novels are more self-conscious and extreme examples of that sensibility, but do you see commonalities in your own work with either one of them or both?

MN: The first few pages of Wittgenstein’s Mistress were utterly key to Bluets. They kind of gifted me the voice from which to speak the book. David’s Reality Hunger is, as I think he would say and has said, more of a theory of the aesthetic he’s interested in than an actualization of it; probably I feel a little distant from its sense of polemic. But insofar as both writers are champions/creators of works of literature that disregard taxonomy, there are definitely commonalities.

TK: What is the role of risk and how does the way that you situate yourself in relation to it change throughout the process of writing a single piece? And if not risk, what are the meaningful terms of negotiation for you in both conceptualizing and executing a piece and the push-and-pull and give-and-take of a piece finding its form?

MN: I appreciate your giving the room for it NOT to be risk, because risk isn’t quite the right register for what I’m trying to do. I mean, the writing has to take risks, something fierce has to be at stake, and I have to write my way into knowing what that is, whether I’m doing scholarship or autobiography or whatever. But taking risks just happens along the way; it isn’t its own virtue. As for form, I think I’m old-fashioned, by which I mean weirdly Platonic: I kind of believe the piece has a pre-existing form that it’s my job to find. I know this isn’t “true,” but it has always helped me to feel I’m uncovering rather than inventing.

TK: What are the personal and political satisfactions of transgression for you? Are you motivated at all by a sense of it or does just being yourself and speaking freely necessarily lead to it?

MN: Transgression presumes the lines are drawn, and then you dramatize your stepping over them. But as Wittgenstein might say, that’s but one way of playing the game. It tells me something about the culture, though, when I just say what I want to say or feel the need to say—when I am just “being myself,” as you put it—and people tell me I’m being brave. What could this mean? As a friend of mine recently put it, being called brave is kind of like saying, You shouldn’t be saying what you’re saying. Not that there isn’t such a thing as bravery, and not that I’d be actively mad at anyone who called me brave, and not that I haven’t called others brave. I’m just saying you learn a lot from the things that other people experience as transgressions, especially if you yourself don’t experience them that way.

TK: Are there aspects of yourself—secrets, taboos, etc.—that are clearly off-limits to you and how do you draw that line? And once it’s drawn are you then tempted to cross it, as by design that line becomes the next standard of risk or transgression?

MN: There isn’t anything off-limits that comes to mind. Maybe I’d know it when I saw it—or, more likely, someone in my life would flag it as such, and I’d be bummed out. I was reading something in the New York Times recently, one of those back page things, by Francine Prose, andshe said something about having to be very cautious about writing about one’s children, since we are their custodians. This freaked me out, since I’m on the cusp of publishing a whole book about my baby, and to a lesser extent, my stepson. But then I rinsed my mind of the moralism by re-reading all the amazing and ethically sound and often feminist writers who have written beautifully and honestly about their children, and I felt OK again. I’m also reading, like everyone else, My Struggle, and I’m really inspired by it. I especially love something Karl Ove Knausgård said in a Paris Review interview, in response to a question about how his intense autobiographical writing has affected his marriage: “Mentioning things doesn’t change anything, doesn’t help anything, it’s just words. There is something much more deep and profound to a relationship than that. Revealing stories and quarrels—that’s just words. Love, that’s something else.” I really relate to what he’s saying here. Likewise, there’s writing, and then there’s publishing—you may have to make negotiated decisions about what you end up publishing, but in the moment of writing, you’ve got to say whatever you want to say. We’ve got to have such spheres of freedom.

TK: We’re the same age. I’m wondering how your senses of motivation or inspiration have evolved or warped orshifted over the years? What are the biggest changes you can recognize in your own processes?

MN: Hey, how’s your 40+? Glad to see you on the other side! Gosh, there have been a lot of changes. All too typical and clichéd to bear recounting…I used to drink a lot and write poetry during fits of feeling enamored with or overwhelmed by the world, I used to live in New York City and scribble deep thoughts and lovely phrases on the fly, I used to understand the urge to write a single lyric poem, I used to, I used to. Now I have kids and I don’t drink and I live in this infernal city in which I drive all the time while filling my mind with completely asinine NPR, sometimes KPFK: maybe you can tell I miss NYC. And yet LA has been undeniably good for my writing—the space out here allows one to imagine and enact larger projects, in art and writing both. I sustain my thoughts, I’m less in love with the sound of an overheard phrase or a good line and more entranced by thinking a hard thought through. I see more art now, I write at circumscribed hours, and so on. It’s OK.

TK: How does your own career seem to you now that you have a good number of successes and you are certainly a mid-career or established writer? Are you aware of having to protect any aspects of your creative practice from your career?

MN: A good number of successes! Mid-career! Established! I don’t see my career with any clarity, the word “career” seems funny to me, maybe the way some artists feel about the word “practice.” When I hear “career” I always think of an amusement park ride, I don’t know why. I guess because I don’t really see it, I don’t feel the need to protect anything from it. Probably I feel what many artists and writers likely feel, which is a “you ain’t seen nothing yet” feeling. No matter what I’ve written, I feel like I haven’t yet begun in earnest, haven’t yet really shown the range of my thoughts or words. More to be revealed, or so I hope.

TK: How aware are you of feeling part of any specific literary/art/subculture traditions? And how does this inform your work, both in conception and execution? Does your writing feel a sense of obligation to anything in particular?

MN: I feel myself to be a part of many different subcultures; most likely it shifts depending on where I am, you know, where it would be more political or surprising to declare what. (I don’t know the context of MAKEmagazine well enough to know which subculture to name/describe here!) I don’t feel any obligations in writing, though, which is great. Save to myself, to my own mind. In my forthcoming book I quote Deleuze and Parneton this account: “What other reason is there for writing than to be a traitor to one’s own reign, traitor to one’s own sex, to one’s class, to one’s majority? And to be a traitor to writing.” This is more complicated than it sounds—but it sounds good, doesn’t it?

TK: How do you hope the people in your life, those you are closest to, will regard your writing?

MN: OI couldn’t talk about the people closest to me as one clump—they are so different from each other andhave so many different needs and concerns. I will say I felt a real sense of relief and happiness when my mother read my forthcoming book, The Argonauts, in manuscript—a book that kind of rakes her over the coals, yet again—and she sent me back a very short email that basically said, “Don’t change a word.” That was a really lovely moment. I’m always looking for permission, support, green lights; I always want the people closest to me to feel the love in what I’m writing, or at least to understand why I do what I do. But I’ve learned over time that they don’t, or at least not always. So I guess I hope that they love me anyway.

This interview first appeared in MAKE #15, “Misfits” Summer/Fall 2014.

Tim Kinsella is the author of two novels, Let Go and Go On and On (2014, Curbside Splendor) and The Karaoke Singer’s Guide to Self-Defense (2011, Featherproof Books). In 2014 he became the publisher and editor at Featherproof Books.

Maggie Nelson is a poet, nonfiction writer, critic, and scholar who teaches at CalArts. Her ninth book, The Argonauts, was published by Graywolf Press in May 2015.

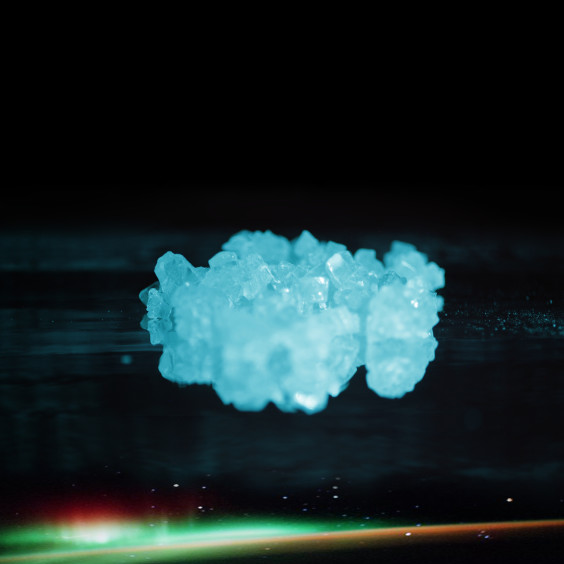

Liz Nielsen is a Brooklyn-based photographic artist who continues to work in the analog color darkroom. In 2015, Nielsen’s work has been shown at the Material Art Fair in Mexico City, at London Photo, and in New York at Denny gallery, Laurence Miller gallery, and Danziger gallery. She received her MFA from the University of Illinois, Chicago and her BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig