by Dustin M. Hoffman

Colombia’s map resembles the shape of a bird, wide shoulders and wings out to both sides, its beak turned up. Cúcuta is a small city on its shoulder to the right, just next to Venezuela. Venezuela is the one that looks like the silhouette of a running sultan with an upturned fist. There are guerrilla stations everywhere in Colombia, like a spreading famine, spreading even over the border into Venezuela’s territory. The guerrillas have forts in the forests.Though nobody seems to know where exactly. Which is why there are rumors, like you should never take la avenida San Juan north, or you should never take a road that looks too hidden with brush because the guerrillas or the paramilitaries could be hiding there, guns to their chest, faces painted in camouflage, waiting to rob you, kidnap you, murder you. Rumors, like rumors of hidden treasures nobody wants to find.

One afternoon in Cúcuta, Nona took two of her grandchildren, Tica and Pocho, through the footpath behind her house that leads to a valley of yellowing trees and dry cracked earth, and opens finally to a buzzing highway and a store for grocers with a lopsided sign that reads Arabastos. Regardless of rumors, the footpath was one they’d taken for years and as far as they knew was safe.

Tica and Pocho took Nona’s hands in theirs, offering their brown thin arms as handrails, because her seventy-five year old body was as tall as their young ten and eight year old bodies, and they could support it. Nona stepped slowly, with her trembling walk, evading twigs and rocks, fitting her American flip-flops, with straps to wrap around her ashy ankles and soles that felt like foam between the arid earth.

From the trees there came a sugary, decrepit smell like overripe mangoes that drooped inside Nona’s nose like a cold. Nona held strongest to Tica, who was stroking her arm. Tica had short black hair and a long swan neck. She wore a thin gauzy shirt and shorts. Her face, long and sad, was easily forgotten. Not many looked at that face, not even the men with their wet hawk eyes. In fact, most men mistook Tica to be the twin brother of Pocho, who looked just like his father: big dangling undershirts, fleshy cheeks and a big stomach shaped like the back of a spoon. There was cawing, whistling, and cackling of birds in the distance. Tica felt the bite of a mosquito on her leg and she swatted at it.

“Do you hear that?”

Pocho heard it first; a big sound in the distance, big like the sound of the ocean, except it came from the sky. The wind picked up, pulling at the hem of Nona’s withered flower dress and rustling the leaves of palm trees that hung down like tongues. In the clearing of sky groups of blue, yellow, and red birds took off in unison and disappeared behind a grey cloud. The sound of the thing they could not see approached them. It came closer, near, just above their heads.

Then they saw it. Helicopters. There, between the tree branches, two of them swinging into view. They swayed their droopy heads with upturned tails between the tree openings like dragonflies looking for something.

“Nona, look, there’s helicopters,” Tica said, letting go of Nona’s hands and pointing up at the two helicopters, giggling, following the flying things with her fingers until they disappeared. Tica’s fingers lingered there, where the trees closed and hid the sky, her mouth frozen in a half smile, until the helicopters were visible again. Their clothes flapped with the wind, and Tica and Pocho continued following them, the giant dragonflies, drawing lines and arches in the sky with their bulgy brown fingertips, laughing. The helicopters like wind rushing into their brains.

Nona drummed her fingers nervously over her grandchildren’s backs, her fingers crawling over to their shoulders, her hands twitching, each finger like a spider leg. She pressed her thin lips together.

No one remembers exactly what happened first. The helicopters firing their guns or the screaming men in camouflage running down the footpath. But one after the other, or both at the same time, Nona wrapped her arms around Tica and Pocho like a belt, and summoning flexibility and strength from a secret padlock of maternal love, picked Tica and Pocho up from the waist and ran with her small legs against the strong wind to behind a scarlet-red rose bush. There, Nona crouched in front of the children who sobbed and covered their ears. She covered each child with one thigh, one arm, and half of her back. She bent her head of white hair down so that all their heads made a triangle.

Nona closed her eyes and she couldn’t help but see the image she had witnessed seconds ago, the men turning around the corner of bushes, dark green paint on their faces, the whites of their eyes standing out from all the green around them. The men’s mouths were frozen in a big O around their yells. “Get out of the way!” they said to each other and yelled other things but Nona’s mind went blank with fear and she couldn’t understand them. Then Nona saw a running girl whip around, a ponytail of black hair swinging with her. And the girl kept running with a gun in her hand, her mouth contorted in a terrible snarl. And that was the last Nona saw or remembered.

Behind the rose bush with its blooming red roses and bowing stems, Nona, Tica, and Pocho heard the sounds of war. Nona’s back stuck out behind her like a mound and moved with her fast breathing. The running fighters screamed like their mamas had died, and everywhere there was the sound of bodies falling down, heavy with death. And worst of all was the combination of disparos, of gunfire like fireworks, muddled with the terrible sound of the helicopters- like suddenly the world was exploding in wild laughter. Nona’s teeth chattered uncontrollably. The children winced against her chest with each loud sound, as if each were like a stab.

Tica and Pocho’s little hands clung like baby bird claws to Nona’s dress and arms. Their crying sounded like the echo of an ambulance in Nona’s ear. There were disparos everywhere. Sparks kicked up dust around them and then were swallowed by the earth. The helicopters thumped in their chests.

The fighters in camouflage hadn’t seen them, the triad of civilians hiding behind the bush, but even if they had been seen it wouldn’t have mattered. After all, the guerrillas, though dedicated to the liberation of the people, deemed civilian death as a small sacrifice. They were after a different kind of liberation, in their eyes a more important one, that of freeing the country of oligarchy. So as to Nona, Pocho and Tica, there was nothing to be done about them.

Nona hugged Tica and Pocho’s heads to her chest tighter and clenched her thighs against them and over the sounds of war said that everything would be alright, prayed to the Virgin Mary for their wellbeing, their paths ridden from evil, their safe return. Their safe return above everything, and if it was a life that the Virgin wanted, to take hers.

“I’ve had a chance to live my life, virgencita, please, but my grandchildren are innocent and young. Mercy, virgencita, mercy,” Nona said, rocking, hugging the two small heads against her chest. In the background the sound of boots swerved and lungedagainst bushes. Then the screaming and the bursts of artillery began disappearing, fading eastward, where there was a jungle.

The violent sounds Nona and her grandchildren had experienced was something so monstrous and loud, like crashing piano keys- blasts, thuds, yelling that whirled in pain and desperation- that even after the helicopters chased the running men down to another part of the forest, even after the sound from the helicopters and the firing grew fainter, it was as if the they would never leave them. They heard it coming from the middle of their souls, a cry like that of a dying animal. Which is why they were frozen as they were, hamstrings taught and muscles so tense that it was hard to ease movement into them. Such was the effort their bodies had endured anticipating death.

Time passed with Pocho’s whimpering, like a baby bird nestled against Nona’s chest, his back against her left thigh, knees to his chest. Urine pooled just in between Pocho’s feet, dripped from the crotch of his red shorts. Tica had her back against Nona’s right thigh, crying and gasping for air, sucking on her thumb, and staring at the pool of urine. Nona’s thighs were rigid stone, varicose veins going up and down her calves. She was hardly breathing.

No one remembered who moved first, but slowly they came out behind the bush, straightened their legs, and looked around suspiciously. They stood and it was Tica who noticed they had cuts, red welts all over their arms, legs, and cheeks with drips of blood like dew in them. Nona thanked the Virgen for not leaving any dead bodies around for them to run into. She imagined the running fighters slinging the dead over their shoulders.

Along the walk home insects’ songs leaked out of the trees. Their skin crawled with the feeling of their hearts being foreign, thumping in their chest as if in a plastic bag. They huddled very close to each other. Together they walked, like a single amoeba. They followed the path to Nona’s back door, staring at their feet the entire way. The feeling of things roaring up to the sky only left them after they stepped inside Nona’s house. There were lonely palm trees that swayed with the wind around Nona’s house and trees that spread like webs with pink and purple flowers. None of them remembered ever feeling so safe to be inside something.

Nona’s eyes turned old and sad like the shell of a cockroach. She hugged Tica and Pocho, forgetting to let go, and for the first time began crying, saying, “We’re safe. We are safe now,” and kissed their cheeks. It wasn’t a kiss as much as it was smacking her lips lightly against their cheek. Her kisses were small and dry like a baby’s.

Scars and their muscles’ soreness were the proof they had of what had happened to them. Nona had shaved off her skin in the back of her thighs. Her body hurt like it had been molido, passed through a grinder. Though she only noticed it four days after, when the initial fear had peeled off her heart and the feeling of her body had returned.

It was impossible to know what guerrilla group the men in the forest belonged to, or who the helicopters were because there are as many guerrilla groups in Colombia as there are kinds of birds. So Nona and her grandchildren lived with their fear unable to dispel it, to point fingers.

Many things changed inside of them. We can speak of it in metaphors if it makes it easier.

They were stained like rosy rocks.

They scratched behind their faces.

There was fear and hope and both of those things couldn’t survive under the same ribcage.

A pillow hot on both sides meant everything.

A distant aunt after hearing the story said, “Look, Tica, look Pocho, there’s no space for nothing but dreaming,” and that meant everything.

So to survive, Nona, Tica, and Pocho reached their hands like tentacles for hope, or acceptance of the situation, or surrender.

Everything would settle. They knew because one day Tica smiled a beaming smile that transformed her in the eyes of those that knew her.

When it happened she had a straight cut of bangs along her forehead and her hair had grown down to her chin.

Somebody had finally seen her, Tica, who was never talked to or addressed, or ever paid a compliment. Somebody had looked her in the eyes and had spoken to her soul. It was her cousin Chula. She said, “Tica, Cleopatra had your same haircut.”

And Tica pulled at her lycra shorts and her thin torso dangled imperceptibly in her wide shirt. “I don’t know who that is,” she said.

“Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt, Tica, she was beautiful and had your haircut.”

Tica grinned, without showing her teeth or wrinkling her eyes. It was a magnificent grin. All day she grinned and walked with her head up. At night Tica listened to the crickets hum, and bubbling with emotion, she ran to her mother and pulled at her dress, and all at once it came out of her mouth, how she had the very same haircut as Cleopatra, who was beautiful, who was the queen of Egypt.

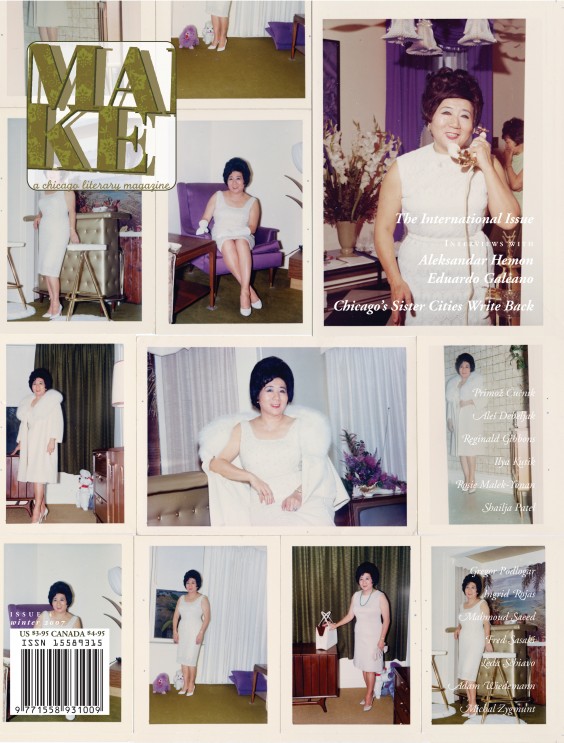

This story first appeared in MAKE #4, “Sister Cities.”

Ingrid Rojas Contrera was born and raised in Bogotá, Colombia. Her first novel Fruit of the Drunken Tree was the silver medal winner in First Fiction from the California Book Awards, and a New York Times editor’s choice. Her essays and short stories have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Buzzfeed, Nylon, MAKE, and Guernica, among others. Rojas Contreras has received numerous awards and fellowships from Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, VONA, Hedgebrook, The Camargo Foundation, and the National Association of Latino Arts and Culture. She is a Visiting Writer at Saint Mary’s College. She is working on a family memoir about her grandfather, a curandero from Colombia who it was said had the power to move clouds.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig