by Mark Molloy

A bit ago, comedian Adam Burke spoke with fellow Chicago-transplant, author Irvine Welsh.

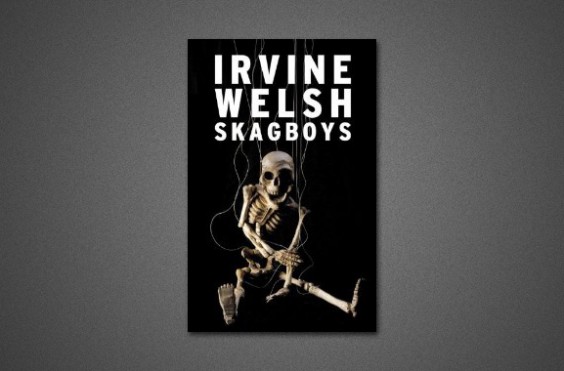

Welsh’s newest novel, Skagboys, has been enjoying critical success in the United States. and the United Kingdom. The author describes the book as a prequel to the international bestseller Trainspotting.

Adam Burke: The book, Skagboys, comes out officially today, yeah?

Irvine Welsh: I think so, yeah, it’s either today or last Friday, I’m not sure.

AB: Did you ever get to the point where you’re so used to book releases?

IW: Yeah, I mean, it’s like a strange thing, this one, because normally it comes out the same time in the USA as it does in the UK, maybe just a couple of weeks after. So I do the US portion then the UK. But this time there has been quite a gap, quite a big gap, so it’s been a strange one to get back into it again.

AB: It’s sort of fortuitously coincided with the Trainspotting USA play that’s coming up in a couple of weeks?

IW: Yeah, yeah. In Chicago here, yeah.

AB: From what I know from what I’ve read this sort of all came together, but it seems strangely planned.

IW: It does, yeah, I mean it wasn’t. It seems that way. But it’s just a coincidental thing. I don’t think that John Mullen who is getting Trainspotting put together had any idea that the book would coincide with it. I mean, I’m glad it does because it means you can talk about two things basically. That the book comes out in the US, and the kind of American Trainspotting comes out on stage is quite kind of interesting.

AB: I just wanted to talk about the Trainspotting USA thing real quick, just in terms of the dramatization of this kind of subject matter. I remember very vividly…when Trainspotting came out in England there being a huge to-do, a concern over the subject matter. Now one of the top shows on cable is Breaking Bad, and there was a show called Weeds that was very popular. So the idea that you can have relatable characters who are involved in the drug trade or addiction, that seems to have become commonplace. Do you have any sort of sense of irony about that?

IW: Yeah, I mean, it’s strange now because, I mean, it’s very much kind of accepted and has become a part of the landscape. It’s very embroiled in the underground economy now. It’s actually difficult to imagine what the world would look like without drugs. So, I mean it’s like it has become part of everyday kind of sort of life. I mean, dramas always focus on kind of Mafioso types who are always doing and supplying drugs and all that, and now they focus on people who are actually taking them or doing kind of small-scale things to get by in the bad economy. It’s a more socially real kind of way of looking at drugs now, in terms of drama. It’s quite strange because Acid House has come out this year in the UK and the tourist board asked us if we could do some posters to promote them. Which is kind of weird because when you look back twenty years when Trainspotting came out, eighteen years when Trainspotting came out, it was just a load of the low-lifes…completely kind of, who were like pariahs, basically. And now it’s just seen as, I mean, Trainspotting has influenced the health education…material with the idea that you know people will take drugs and all that, and it starts off, the reason people take them is because they’re good and they’re fun, and then there’s the situation when it goes bad. So it’s that kind of trajectory, the kind of reality trajectory of drugs is kind of much more in the debate and into the landscape now.

AB: Do you think you have more perspective on how completely wrong-headed the war on drugs was? Because as you say … at the time there was this idea that there were regular people and then there were junkies. And that seems naïve now.

IW: Yeah, there was no casual kind of clubbers who went out on the weekend and then tried to find a job during the week. The whole thing was kind of strange and weird and unreal, and I think that that different kind of reality is kind of accepted now, you know, about how things actually are. I think the Trainspotting kind of thing did change a lot of that, or at least contributed in a way to that kind of debate and that new sense of reality. I think the thing now is to get fewer politicians who will say, “You know this is what we need, this is war against drugs, this is war on drugs and all that.” But the policy is very much one of containment now, there seems to be that kind of thing: let’s kind of ignore it, and we won’t really kind of deal with it on any kind of, on any kind of viable sort of sensible level. So there seems to be instead of the old war against drugs policy, there seems to be now not any real policy. Some agencies are advocating that the war is education, the war is rehabilitation, the war is methadone containment, but it seems very hodge podge and piecemeal and lacking: “This is what we are, and this is what we’re doing.”

AB: I know you’ve talked about this in other interviews and certainly with your last interview with MAKE: Would you say that Skagboys has more of an overtly political or sort of social context or a sort of more macro picture that Trainspotting didn’t have so much?

IW: I think so in some ways. Trainspotting was very much looking into the subculture and looking outside to the rest of the world through their own kind of lens, and through their own sort of stuff they’ve got going on. And it wasn’t really referencing the world because the world had shrunk to the point that they just wanted to kind of get sorted out, you know, to begin to get by. So the world is kind of shunned. The parameters are kind of shunned. Skagboys is more looking at what happened to society in general and the pressures on local communities, and the pressures on local families, and the pressure on individuals.

AB: I was wondering if you had this sense while writing [the book]—since you’re writing about a period of time thirty years ago now, the early to mid-eighties—were you surprised with how timely you were in addressing these [contemporary] issues of inner-city depression and joblessness?

IW: In Britain, and probably in America as well, we are coming off of thirty years neo-liberalism where you haven’t really had any kind of challenge to an economy of mass unemployment. As long as you have mass unemployment, drugs pretty much win by default, because there’s no other way to make a living or get by, other than stealing, hustling, and dealing. There’s a lot of pain around too, so people want drugs for the pain, as well as the celebrating and partying. So we’re in the position whereby there’s not a lot. You can start at Margaret Thatcher and go through David Cameron—there hasn’t been a real attempt to reconfigure the society. You have an economic and kind of fiscal policy now whereby in the sense of globalization the very, very rich can take massive sums of money out of countries and that kind of money…become[s] almost like they’re in a super state of their own, kind of away from countries, so that they can make themselves not part of the equation. So, you have so much money that is taken out of the economy, because it is not available for taxation; it’s not available to be spent in the economy—far less redistributed in any way. Basically, there’s that kind of hiatus. The whole thing to me is like, we keep hearing about how the emergent economies of, you know, Russia and India, China, and Brazil are going to become much more like Britain’s and America’s, but all that I’m saying is that I think our economies are going to become much more like those places. I think in the next twenty, thirty years you’re going to see middle class people in America and Britain fall into the poverty chart—the kind of underclasses created by Thatcherism and Reaganism’s kind of expedience. I just can’t really see—unless the operational laws of society can share some of that kind of wealth around—I can’t even see any alternatives to how things would work out.

AB: One thing I like about the book was that I never felt I was being lectured to. Certainly one sense I got was that drugs are the provision of the poor, but you also get the sense, (sorry for the fancy Latin term), that poverty is the sine qua non of the drugs trade. The drugs trade can’t exist unless there are poor people—masses and masses of poor people.

IW: You need people who are ready to take drugs, who want drugs. The people who want drugs to genuinely celebrate, well, that market is never going to be as big or as stable as people who want drugs for some kind of pain. So if you got poverty, not so much kind of, I mean monetary poverty as well, but the lack of opportunity—the kind of boredom—the lack of opportunity so that people don’t feel compelling dramas through work and through education. If that’s all gone, then you have this kind of thing where people who are living kind of day to day and they’re having the odd sobering up. Maybe there’s a good time and festival and all that, but most of the time, the drug experience is going to be all about just kind of getting by, and getting through, and making life less hard.

AB: The book starts with this incredible sense of belonging, beginning with Mark’s tentative involvement with the Miners’ Union and the strikes. When you were revisiting this material—I know some of it was sort of written new for the book and some of it was sort of unearthed—did you have a sense that in the ‘80s there was a different sense of camaraderie or a different sense of what the working man was due or what they could do, as opposed to now?

IW: I think so; he has that kind of bourgeois consensus—a sort of welfare and social democratic nation, kind of unionized. And it was, in a sense, that kind of social progress and what the working class people were entitled to, you know, we’re in the second world war fighting Nazism and all that. That kind of social progress needs to continue to be made, and the liberal party (can we link or clarify what this means? Is this “Liberal” party or the party which was more liberal. I know practically nothing.) was talking about industrial democracy and workers on the board (what does this mean?) as being the next stage, which kind of seems miles and miles away now. I wanted to capture that kind of sense of community. Then it kind of broke down under Thatcherism—the smooth era of the scab and the grass. It was more also about an era of the industrialization, that’s why I started with a group trying to break into a factory, trying to stop people from getting into the factory from (through?) the picket lines and all that. And I ended up with them trying to break into the factory. That to me is the industrialization, and that kind of movement from unemployment to the drug trade and underground economy was all kind of bookended by that imagery of the factory, basically.

AB: Do you think that people have short political memories?

IW: Yeah, I think it’s not so much a short political memory, but you’ve got a couple generations that have grown up without any employment, without any educational prospects, and people who live in the boonies growing up with drugs everywhere. That’s the kind of norm for them. Within that context, it’s difficult to talk about memory for people like that. You’ve got maybe two or three generations of people that are unemployed, kind of regularly, so there is nothing else in terms of that.

AB: I was struck by a story recently. I think it was at the TUC (Trades Union Congress), someone was chided for selling t-shirts that said something like TUC or union workers will dance on Thatcher’s grave. I was surprised at the surprise of that. You know what I mean? I remember that sort of language being very common.

IW: I mean, Thatcher became this real horrible symbol, and everything became about the class war, and have we won the class war, in the ‘80s. Not defending Thatcher as an individual, but she was just such a symbol. There was much more to it than her. There was the Labour Party and Denis Healey who went to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1976 and started the whole Marxist thing. There were social and economic changes, which were responded to in a much different way than in the European social democracies than they were in Britain. You can see the effects of that, the results of that. One thing I tried to do was to draw a difference, in the way—why people got into heroin and the changes in society, but also to make it about the individual as well. I mean Spud, for example; he’s not anything else. He doesn’t have any education, no prospects, no qualifications, and so when all the manual jobs in the economy collapsed, people like him were just completely fucked and completely isolated. They were kind of made redundant, not just economically, but in all sorts of ways. And then you got somebody like Alison, who had suffered a bereavement, and the pressure of being this kind of girl about town, who suddenly has to look after her younger siblings and replace her mother, and she’s not really cut out for that … And Renton … can see that Sick Boy is desperate not to talk to his father after all these years. And the symbiotic relationship those two have, Sick Boy and Renton, not many junkies find anything like that.

AB: There is this sense as well, that old thing, “I’m not bad, but I’m not so-and-so bad.” Where you have someone around who you can look down upon.

IW: Yeah, I think that’s the thing. I mean, that’s the thing with Begbie who kind of jumps fashions and he was down on Renton for being [a junky]. He wants alcohol and cocaine, which he’d probably get into later on because he doesn’t want to be staring at walls. He wants to be out there punching people.

AB: There’s a great quote about Nelson Algren*, which I don’t have at hand, but someone else is writing about the reason that he thought Algren worked so well is that he recognized that his characters had been dehumanized—and dehumanized people don’t behave very well. And I sort of recognize that in your work as well, where the characters that you ostensibly have to care about are also going to do horrible things to themselves and other people.

IW: Yeah, I think you have to acknowledge that. You have to acknowledge when people are brutalized in that way that they’re not often easy to be around. My mission as a writer was to look at how people fuck up, how, when things are going well people make bad decisions to mess things up. And why when things are going bad, they get into a worse situation to compound it. So much of it is in our culture, the fear of success, the fear of failure, all these kinds of things that conspire and also that we need for the compelling drama that we have as well. They often inspire us to make these decisions that often aren’t great decisions.

AB: About compelling drama, I think you even have Spud articulate it, “Just something to do and a tale to tell.”

IW: Yeah, basically, being a part of that drug-and-sub culture that gives him that kind of thing you know? When you get older and you learn that mindset—that everything is going to be this fucked up, narcissistic drama. It’s something you can enjoy and get into when you are younger, but when you see the people who are older who have just become so weary and difficult to be around … A lot of people do get stuck in that loop.

AB: You said during the reading [at the Metro] that you could tell what bits you’d written a couple decades [ago] and the bits you’d written more recently. I for one couldn’t tell.

IW: Ah, that’s good.

AB: During the reading at Metro, someone asked you about authors that influenced you, and one of the writers you mentioned was Evelyn Waugh, which surprised me at first, but on reflection it totally made sense. In particular, your work reminds me of Vile Bodies. Given this and the frequent references to Tender is the Night in Skagboys, can you talk a little a bit the commonalities between your work and these social commentaries from the 1920s? Do you think there is something in particular about the 1920s that strikes a chord with you?

AB: I thought you actually captured the mindset of people in their early twenties or people who are just entering their early twenties. And I feel like they’re very world-weary for people who are just coming out of college.

IW: I think … when you write it’s quite easy to do the ages you’ve lived through. I find it really hard to write about older people. I find it hard to get into the mind of any era that I haven’t quite experienced yet. I find it hard to do. I find it hard to write about people quite the same age as me, usually a little bit younger or a lot younger. Anything that’s the same age as me is difficult because I haven’t processed it yet.

AB: I sort of hate to ask this type of question having grown up in Britain myself, but I think there is a world-weariness and eagerness to act like an adult for people in the age range from 18 to 21 [in Britain] that maybe comes from the pub culture. I think it might be surprising how sort of jaded people are. Do you ever get that from American readers?

IW: I think, going back to that whole squeaky clean American sort of thing, in that kind of zestiness, there is a sort of very louche-ness about British young people’s culture. A lot of it is about what you said: being able to drink when you’re 18. And if you’re able to drink when you’re 18, then you’re going to start drinking a lot earlier. You can get people who—by the time they’re in their early 20s, and they’re at the universities— it’s like they’ve lived quite a few lives. In America, you’re just able to drink at 21, to get into a bar at 21. There is a sense of, a kind of freshness and zest here of people in their 20s, because they’re not simply passed out.

AB: I think you capture very massively, a very British thing—this age-old cross-section between football, religious, and political affiliations. And I was wondering how much of that needed to be addressed in the Trainspotting USA adaption. I know that sports are often referred to as a religion over here, but I don’t know that it has that deep political root.

IW: I don’t think it does. The difference between sports in America and sports in Britain is that you pick sports club and franchises in America that are very much about, that are very much originated in the locality you know. So you get some teams like the Green Bay Packers and all that who come from an industrial workers thing. British team sports are about that as well, but they’re much more about industry and the industrial revolution, and they come much more out of distinctively working class industrial roots. So there’s more of a visceral, aggressive partisanship in British sports than in American sports. There’s something very much embedded. It’s not just about who you are, but about your whole history. It’s almost like your whole DNA is laid there, at least, traditionally. It’s become more TV-dominated and money-dominated, a bit more like American sports. But in old school sort of working class times in particular, it was more an unraveling of your lineage, basically.

AB: Something else you touched upon in the reading, where I felt like the perfect nexus of all that, was the publishing of the report of the Hillsborough disaster. That seemed like a tragedy that just sort of happened through bad planning and is now laid bare as a conscious sort of attack or a way that the state sort of vilified [people].

IW: If you watch the commonality between the miner strike and Hillsborough and because of their assistance to Thatcher in breaking up the miner strike they were given kept carte blanche just to do this. Not just by Thatcher and the Tories but by the whole rubbish[us11] of the entire city. [Newspapers][us12] ruthlessly portrayed Liverpool as this place that’s kind of like thieves and degenerates; as this city that really felt sorry for itself. I lived there for a while and spent a lot of time there, and it’s just not. It’s just not at all what the place is about. I could never understand that poor public perception of the place—and how it changed from being this warm, working class kind of town, where people were basically decent and good—and fun loving and a bit cultural as well, with the Beatles and all that. And it changed into being a place of thieves, and robbers, and cutthroats, and all that. It was a basically a result of that whole kind of …[us13] dehumanization.

AB: Were you able to catch any of Mr. Danny Boyle’s Olympic spectacular?

IW: I didn’t see it, but I heard all about it. He did a fantastic job to try and reinvent, it was almost like an inspirational kind of social democratic Britain that he reinvented that is almost all but gone. He basically showed Britain what was lost.

AB: It’s really interesting that you say that, because I felt the same way too. I thought there was more sly commentary going on there than people perhaps were aware of.

IW: It was definitely political. It was very, very, clever.

AB: Final question is from the book: I was able to pick up most of the slang … but I don’t think I could give you a working definition of what “radge” means.

IW: Yeah, “radge” is two things. It’s either a person that’s kind of crazy or doing something that’s crazy, but it can also be “good” as well. It can be good or bad. It’s become more of an emphasis is the thing.

AB: I feel like a lot of British slang is like that, where you’ve got three or four different definitions to worry about. It can be very fluid, yeah?

IW: I mean, definitely. “Cunt” is an example, it’s got like a half a dozen different uses.

AB: Actually I think that’s a great place to end the interview. There’s an old dictionary of profanity that refers to that word as the “venerable monosyllable.”

IW: Chuckles.

This interview took place over the phone on October 20, 2012 and was transcribed by Connor Goodwin.

From Adam Burke:

* The quote I (Burke) was trying to think of is by Kurt Vonnegut remarking on the work of Nelson Algren, in which he said: “He broke new ground by depicting persons said to be dehumanized by poverty and ignorance and injustice as being genuinely dehumanized, and dehumanized quite permanently.” This is from his introduction to the 50th Anniversary edition of The Man with the Golden Arm, in which he goes on to quote Algren as saying (of the poor), “Hey — an awful lot of these people your hearts are bleeding for are really mean and stupid. That’s just a fact.”

Originally from the UK, Adam Burke began performing stand-up after writing a piece on comedy for a Chicago magazine. Before long, Burke became a fixture at Midwestern shows and showcases. His absurdist, verbose comedy covers not only the vagaries of life in his adopted hometown of Chicago, but also the usefulness of mammoths, dogs who study law, and the importance of gangland grammar. He has appeared on the Bob and Tom show, WGN 720 AM radio, and the Benson Interruption Podcast, and was listed as one of the Top 20 Comedians in Chicago by Comedy.com. Adam has appeared at the Bridgetown Comedy Festival in Portland OR, and as part of the Just for Laughs Chicago festival for three years running. In addition, he has opened for a wide variety of comedians including Jeff Ross, Maria Bamford, Bo Burnham, Brendon Burns, and Jake Johannsen.

Irvine Welsh was born in the great city of Edinburgh, Scotland. He can’t quite recall if it was Simpson’s or Elsie Inglis maternity pavilions. In fact he remembers little of the birth, though his mother assured him later that it was fairly routine. This selective memory at key points in his life would continue. What he seems quite certain of is that his family moved from their tenement home in Leith, to the prefabs in West Pilton, and then onto Muirhouse’s maisonette flats. READ MORE

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig