by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Melville House, 2010 | 416 pages

Jean-Christophe Valtat thinks in French. Generally, he writes in French. Three previous works of literary fiction: Album, Exes, and 03 being proof of this. Aurorarama, his latest novel, a steampunk tale of revolution and frostbite, is his first book written in English. And while Valtat may borrow the Queen’s English for 400 pages, the ideas and subtle humor that power this experiment of story and style are French through and through.

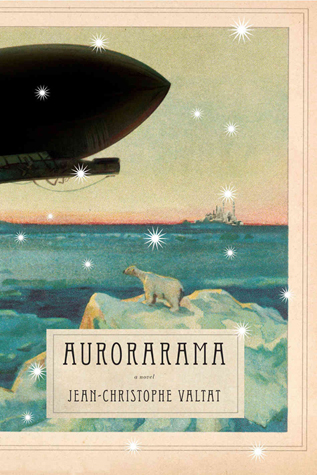

Set in an alternate version of the early 20th century in the city of New Venice, “The Pearl of the Arctic,” this is a world of frigid temperatures, stunning architecture, outlandish technology, dandies, secret societies, top hats, swords concealed in canes, and anarchists in dirigibles. Elements of the supernatural and the fantastic mix and coordinate seamlessly with the, for lack of a better word, realities here. In New Venice, in winter, the light from the sun – as it peeks its head above the horizon, only to duck back under a few hours later – creates strange, odd angled shadows across the city, and novel. Winter and the near constant night that accompany it at this latitude set the stage for what is a dark, quirky story, with about as many characters, twists and turns as there are Eskimo terms for snow. There are, for example, the Seven Sleepers, the founders of the city prophesied to someday return; there is the fantastic Phantom Patrol, the undead explorers who roam the arctic to keep it safe from man; the Kiggertarpok, or “polar kangaroo,” the spiritual power animal/protector of the arctic; the Ghost Lady, the force responsible for pushing our protagonists along, etc. The city itself is just as fantastic, styled with Victorian architecture and dress and protected by the worst of the arctic weather by the Air Architecture, a sort of hazy airwall of methane fumes that surrounds the city. Also, the sky above is presently occupied by a mysterious dark airship, piloted by god-knows-who, and for god-only-knows what reason. And circulating within it all, fuse lit, is a manifesto, A Blast on Barren Land, an anonymous call to arms against the corrupt Council of Seven whose secret authorship everyone seems to know.

The story begins when a driverless sled pulled by a team of dogs arrives at the northernmost fringe of the city, the body of a woman in tow. The “Scavengers,” the people that discover the woman are an odd bunch. Garbage collectors, technically, the Scavengers are a reclusive and secretive caste of untouchables, and feared because of it. They dress in “plague doctor” attire: black overcoats, white bird masks, and wide-brimmed hats. The woman they discover is wearing a black dress and clutching an antique silver mirror with a cryptic message etched into the back, but most disconcerting is that the sled has come from the north, and north of there “there was nothing, and maybe not even that.” The novel revolves around, and hops back and forth between two characters; friends, Brentford Orsini and Gabriel d’Allier. Orsini is from a noble lineage of New Venice. He is an administrator and runs the greenhouse, a massive complex with a sordid past, but, under Orsini, what promises to be a bright future. Gabriel d’Allier is a dandy, flamboyant in his mannerisms, dress, drug use, and promiscuity. He is a professor that professes little other than his addiction to women, drugs, and the hipster music scene that seems to be the pulse of the frozen city. Both Orsini and d’Allier are hounded throughout the story by The Gentlemen of the Night, a stylishly garbed secret police force.

Valtat’s prose is often lyrical, and sprinkled with wordplay, poletics versus politics, for instance, and his back and forth dialogue is laced with Victorian tongue in cheek politeness and Wildean wit. Early in the novel, d’Allier is confronted in a restaurant by Sealtiel Wynne, d’Allier’s adversary throughout the novel, and a member of the Gentlemen of the Night. Wynne begins:

“I am truly sorry to disturb you, but it happens that it is my unfortunate duty to ask a favour of you. Do you think, Mr. d’ Allier, that you could follow us to a more comfortable place?” “I suppose I could. But would I want to?” “Let us say that it would be very kind of you, if you did.” “How much I regret it, that I am not reputed to perform random acts of kindness.”If New Venice had a sister city it would be Fritz Lang’s Metropolis for its mix of messages, technology, and, last but not least, style – a comparison further played out by the video trailer the publisher put together to advertise the novel. Black and white, and moved along by a chilling soundtrack and title cards, the video captures the heaviness of what the Alaskan Inuit call Qarrtsiluni – the moment spent waiting in the dark for something to explode.

Coordinating with the imagery of the trailer, the novel is illustrated sparingly by period-perfect etchings that capture sublimely the novel’s timbre, inviting the reader to step into the page and take a seat in the parlor. Aesthetically, Aurorarama is an experience to be savored – something we’ve come to expect from the catalogue of Melville House.

Thematically, Aurorarama sits on the shelf next to Orwell’s 1984 and Vonnegut’s Player Piano. Like Player Piano, the revolution in Aurorarama is begun by a member of the upper class. But where the ruling government in Player Piano sought to make the middle and lower classes unnecessary through automation, the Council of Seven in New Venice would gladly see its citizens as addicts and the economy built on the export of narcotics, such was the previous use of Orsini’s massive greenhouse. Where 1984’s Big Brother is omnipresent in reality, bleak austerity the fuel of the regime, the Council of Seven’s omnipresence is established in the perception that it is powerful, New Venice bathed constantly in pomp and circumstance. And yet, on this metaphorical bookshelf, Aurorarama sits just on the other side of a bookend, separating it from these dystopian pieces. For Aurorarama is not a dystopian tale. While it shares similarities with both 1984 and Player Piano, it remains a hopeful novel. At a latitude covered in darkness, Valtat’s characters create their own light. Like the Aurora Borealis, the protagonists in Aurorarama are luminescent, and their ambitions sparkle like the ice they are carved from. Valtat, like the magician Handyside, one of the story’s antagonists, is a trickster. The deck he is dealing has many more than 52 cards, some of which are tarot. Like the proclivity of a shadow to distort the reality/truth until it is exposed to the full light of day, Valtat plays with the shadows of a past the reader is not privy to, keeping us one step behind and half in the dark as he waits for the sun to rise and the story to play out before showing us his cards. But while fantastic, Aurorarama is not fantasy; what appears as fantastic is ultimately explained: a sort of surreal explique, if you will.

According to the book’s jacket, Aurorarama is “unlike anything you’ve read before,” and for chucks at a time, this statement is relatively true. Aurorarama is a wildly imaginative novel. It is packed with language that will send you searching for your Merriam-Webster, and have you Googling for French to English to Inuit translations. It is a novel packed with style; perhaps, on occasion, overly so. For instance, our protagonists, a number of times, are excessively moved by the lyrics to “polar pop” songs that don’t come off as poignant or enlightened as it seems they were intended to. While not as absurd as the rap lyrics crafted by DeLillo for his otherwise unique and intelligent novel Cosmopolis, they do seem a bit out of place, overused, and flat. Despite coming across at times as trying to be a little too hip, the novel has enough imagination and flair to make the few failings and (not infrequent) typos seem like tiny puddles in an otherwise flawless frozen pond, perfect for skating.

SD Allison was born in Nebraska. He is the descendant of farmers, teachers, and men with bad lungs. He is the father of a little boy with autism. His first novel, Beneath the Plastic, was published in 2006. He is currently a senior copy writer for a marketing/ad agency.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig