by Killian Quigley

Published by University Of Chicago Press, 2010 | 96 pages

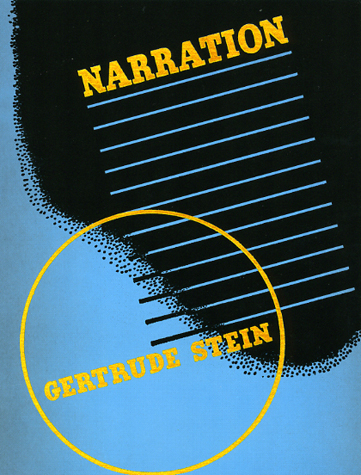

The font is small, spaced just too widely for a paperback; the margins tiny; the page numbers thick, blocky, and oddly large. The whole: leaflet-like, zine-like, like a rushed work in progress. “Literature we may say is what goes on all the time history is what goes on from time to time and this is what is terribly important to think about in connection with narrative”— Gertrude Stein telegraphs us through these sheets in an unseizable voice whose blanked-out punctuations we keep needing to imagine but can never confirm. “In America life goes on but not from minute to minute and each minute being filled full of it.” Meaning sloshes around in the short words she poses and transposes from, towards, upon each other. Instead of smoothly following her lines, our eyes are constantly arrested. Where is this word’s weight? What are its latches and its bridges?

This book is Narration,a series of four lectures Gertrude Stein originally delivered in 1935 at the University of Chicago—long out of print, and now reissued by the University of Chicago Press. Stein was invited to give these lectures as part of a cross-America tour shortly upon the publication of the suddenly wildly successful Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.She traveled back to make this tour after a long stay in Paris—during which she and Toklas had become romantic partners, and she had established their shared salon as a central meeting place for rising artists from Pablo Picasso to the young Ernest Hemingway. The lectures are not transcripts or notes but careful compositions Stein had drafted beforehand and merely read out loud at her Chicago appearances.

As a theoretical piece, Narration is abstract if thickly woven. Though its aim is clearly to teach and to convince, it is not a work of analytic philosophy. Its methods are closer to those of a poem, and an aggressive poem at that. Mostly the field this poem pries is wide and empty; we roam through it on the bullish backs of beasts like “history,” “narration,” “literature,” “the newspaper,” “genius,” “American” or “English language.” These steeds collide and cooperate; they collapse occasionally but are always brought back afoot by Stein’s characteristic unapologetic fervor and certainty. The insights Stein works through are similar to ones often expressed by other modernists. Among many others, Stein connects modern genius to youthfulness. She cautions against but is also fascinated by the pure externality of the newspaper. She draws and redraws lines between history and literature as forms of narration, between British and American English. Examples are few and uncontextualized. Here and there a phrase, an ad, an anecdote. “I love my love with a b because she is peculiar.” (sic)“Let’s make our flour meal and meat in Georgia.” “The wailing of the dead soldiers in L’Aiglon.”

Especially for a reader unfamiliar with Stein’s writing, it is in her fervor, in the impatience with which it bursts through Stein’s imposed lecture form, that the main rewards of reading Narration are to be found.Stein’s prose surprises, stuns, blocks easy mental or emotional exit and entry. Corralled in this fashion, we are subjected to chiropractic shifts and jerks of syntax. “I once said and I think it is true that being a genius is being one who is one at one and at the same time telling and listening to anything or everything.” Stein’s phrase surrounds and twists us, pulls us in and out of aphorisms. Before our eyes, her language breaks open into a sort of cubism. Stein’s forceful, muscular verbal acrobatics—which require such effort to keep pace with—remind us of the strain needed to first forge modernist conclusions we now often tend to take for granted. Narration becomes not only a lesson in modernism but also a lesson in the persistent difficulty of the mental spaces modernism opened. Stein’s mental meanderings reproach us for the false confidence with which we might want to treat the paths and choices she maps out for us as already and always, and easily our own, as if the liberations and breaking points Stein works through had cost us nothing—would cost us nothing—in effort, loss, or pain. If Narration does not have the depth and complexity of, say, Tender Buttons, this only makes it more self-evident, and more instantly usable, as such a place of self-scrutiny; as a lesson that humility about our modernism may be the greatest form of bravery we can still, even now, muster.

Marta Figlerowicz is a graduate student in English at the University of California, Berkeley. Her criticism and creative writing have appeared in, among others, New Literary History, Dix-huitieme siecle, Prooftexts, The Harvard Advocate, and The Harvard Book Review.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig