by Barrie Jean Borich

On the morning of July 30, 2002, a crowd of more than 15,000 spills out of the elegantly decaying art deco hulk of the old convention hall on the boardwalk in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Surging across the boardwalk and down to the beach itself, the crowd is littered with small American flags and handmade signs held aloft for the cameras. “NO BETTER COLORS,” reads one, melding corporate promotion and resurgent patriotism in a single phrase, with the network’s initials, NBC, highlighted above a smaller slogan at the bottom of the sign, “RED, WHITE, AND BRUCE.” Inside the convention hall—and live on TV screens all across the country—Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band are concluding their four-song set with the first public performance of “Into the Fire,” a dirge for fallen rescue workers of September 11, in which echoes of country blues and gospel-tainted affirmation struggle for precedence. “The sky was falling and streaked with blood,” Springsteen sings over the desolate intertwining of his electric guitar and bandmate Nils Lofgren’s slide, while a line of women in brightly colored bikini tops out on the beach sway in time to the music and wave at the cameras.

This special broadcast of the Today show, as its hosts Katie Couric and Matt Lauer continually remind their viewers, is coming live from Asbury Park in celebration of the release this very morning of Springsteen’s fourteenth album, The Rising. Not only is The Rising the first studio recording by the reunited E Street Band since the multiplatinum Born in the U.S.A. in 1984, but the album is also being consciously marketed as a work about September 11. As Time declares in a cover story out on the stands this same morning, The Rising is “the first significant piece of pop art to respond to the events of the day.”

Yet this deliberate association with September 11 is controversial too, particularly in light of the album’s massive marketing campaign (which has not only landed Springsteen on the Today show and the cover of Time but will also include a two-part Nightline interview as well as another cover story in Rolling Stone—accompanied by a five-star review of the album—and other interviews with major media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio). In the Time cover story, Charles R. Cross, who founded the Springsteen fan magazine Backstreets, says, “I think we want art that can deal with [September 11], but it’s still such an uncomfortable thing, and it’s still pretty fresh. Frankly, the commercial element of it really scares me.”

Perhaps if the arc of Springsteen’s career didn’t seem to resemble so closely the familiar pattern of an older pop star triumphantly returning to prominence after long years in a commercial and artistic wilderness, the scope and intensity of the marketing of The Rising wouldn’t seem so troubling. But ever since Springsteen deliberately attempted to step back from the frenzy of Born in the U.S.A. in 1984, his career had seemed more tentative. Though Columbia Records sold more than fifteen million copies of Born in the U.S.A. and Springsteen was transformed, not entirely unwillingly, into a national icon, he was clearly uncomfortable as a pop star playing to such a massive audience. After releasing the quieter, more introspective Tunnel of Love in 1987 and then breaking up—for a while at least—The E Street Band, he veered between wildly different paths: first recording and touring with other musicians to lukewarm reviews (leading Entertainment Weekly to ask on its cover in 1992, “Whatever Happened to Bruce Springsteen?”), then offering an album of stark protest songs and hushed acoustic ballads of anomie and dislocation with The Ghost of Tom Joad in 1994, and finally releasing archival recordings and reuniting The E Street Band in 1999 for a long tour that celebrated the band’s history but offered up few new songs. Until The Rising, that is—an album of new songs consciously offered as a major statement and backed by a huge marketing drive. For all of Springsteen’s sincere intentions to respond to the events of September 11, The Rising is also, of course, a good career move.

But there’s no room for any such doubts on the Today show on the morning of the album’s release. Instead, the broadcast focuses on Springsteen’s familiar image as a man of the people. In a taped segment before the band’s live performance, Springsteen and Matt Lauer wander casually through Asbury Park in jeans and sunglasses, while Springsteen points out some of the businesses helping to fuel the town’s slow urban renewal. And in a live segment with Katie Couric, the program reprises a much-noted story about a fan whose path famously crossed with Springsteen’s a few days after September 11 and whose words helped inspire The Rising.

The fan, Edward Sutphin, is here, in fact, standing outside the convention hall and telling his story to Katie Couric, looking as comfortable on-camera as any of the Today show hosts, in a loose white shirt and black pants that perfectly complement Couric’s white summer dress. He talks first about a friend who died in one of the towers. “We grew up together on the beaches of the Jersey shore, played football together,” Sutphin says, as if he were describing a couple of characters from a prototypical Springsteen song. When Couric notes that he spent forty-eight hours after the towers fell with his friend’s wife and children waiting for news and then suggests, in familiar empathic tones, that those two days “must have been an excruciatingly painful period of time,” Sutphin explains how after a while he had to get out and went to the beach to think. “I pulled into the beach,” he says, “and I saw Bruce pulling out and I rolled down the window and I yelled as hard and loud as I could, ‘We need you now.’”

This story, which Springsteen told to Jon Pareles of the New York Times in an interview that appeared a few days earlier, offers an almost perfect distillation of Springsteen’s myth. All its details seem to pass before the familiar stations: the Jersey shore that Springsteen claimed in so many songs, the chance encounter through a rolled-down car window, the fan’s fervor, and the everyday availability of the star himself, just out for a drive, unaccompanied by a coterie of bodyguards or retainers like Elvis’s Memphis Mafia or Michael Jackson’s poisonous enablers. Even Springsteen’s determinedly humble response only burnished his iconic qualities a little more. “That’s part of my job,” he told Pareles, characteristically using the language of an ordinary laborer to describe the life of a rock star. “It’s an honor to find that place in the audience’s life.”

And indeed, the performer who appears on the Today show seems, for the most part, exactly as Sutphin describes him to Couric, a unifying figure who’s “given us so much” with his “songs of love, hope, defiance.” To the live audience in Asbury Park and the millions more in front of TV screens all over the country, those are the tones that surely seem to emerge from these new songs they’re hearing for the first time. Without the printed lyrics that accompany the album—for those, that is, who still buy albums—or any sense of the careful sequencing of songs that Springsteen meticulously designs for his albums, it’s other, less subtle things that register: the martial beat of Max Weinberg’s drums; the layers of electric guitar and keyboards; the way Springsteen’s designated sidekick Steven Van Zandt’s nasal yard-dog vocals wrap around Springsteen’s own workingman’s growl; and, of course, those choruses that lodge in the memory so easily. Who really knows during the first song what Springsteen means when he exhorts his audience to “Come on up for the rising”? A small segment who have read Pareles’s article in the Times a few days ago might be listening for hints that the song is in fact, as Pareles described it, an anguished account of “one man’s afterlife,” but for others—maybe a few in the on-screen audience who raise their fists during the chorus—it might be a call to arms, a warning to America’s attackers of a rising against them. Just as in the next song, “Lonesome Day,” it’s the jubilant chorus that makes the biggest impact, Springsteen’s increasingly ecstatic assertion that even in the face of this lonesome day, “it’s alright . . . it’s alright . . . it’s alright . . .” What’s not heard, by many at least—what will go entirely unremarked in fact in virtually all of the public discussion of the album—is a clear warning in the last verse about the potential political manipulation of September 11 and a hint too of a more complex view of its causes: “Better ask questions before you shoot / Deceit and betrayal’s bitter fruit.”

This, after all, is The Boss, on screen now pounding out riffs and choruses with The E Street Band, the iconic figure who is most recognizably himself during the third song, “Glory Days,” one of the hits off Born in the U.S.A. Everyone seems to relax a little during this song, the band easing into a time-tested groove after working carefully through two new songs from The Rising, Springsteen and Van Zandt mugging happily for the cameras, for a moment more like Jackie Gleason and Art Carney than Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, while the noise from the crowd grows. All through the audience, as the camera pans across the convention hall and out on to the beach, people clap and dance and sing along with every line, the whole raucous scene an apparent confirmation of what Edward Sutphin had told Katie Couric just a little earlier: “Nobody brings us together like Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band.”

But, of course, the genial rock star romping through “Glory Days” on the Today show is only one side of Springsteen. Not long after that performance, as Springsteen and The E Street Band toured the world in support of The Rising while the Bush administration lobbied to invade Iraq and then launched Operation Iraqi Freedom, a different side of Springsteen emerged in concert. If The Rising had seemed largely apolitical to most reviewers, now politics couldn’t be avoided. At a stop in Atlantic City on March 7, 2003, only weeks before American forces would cross the border into Iraq, Springsteen cautioned his audience about the lines “I want a kiss from your lips / I want an eye for an eye” from the song “Empty Sky” (which he’d remade from its edgy percussive setting on The Rising as an acoustic ballad on tour). Once again, as on other nights, those lines brought cheers from the crowd. This time, though, Springsteen responded after the song. “I wrote that as an expression of the character’s confusion and grief,” he said, “never as a call for blind revenge or blood lust.” And by the last leg of the tour, as the initial justifications for the invasion had dissolved and the true costs of the occupation began to emerge, near the end of every show Springsteen offered what he termed a brief public service announcement before an explosive version of “Born in the U.S.A.,” his own often-misunderstood lament for another war. “Protecting our democracy that we ask our sons and daughter to die for is our sacred trust,” he said, “as is demanding accountability from our leaders. That’s our job as citizens. It’s a time to be very, very vigilant out there.”

And yet, not surprisingly, instead of bringing his audience together, Springsteen’s political statements—including his endorsement of John Kerry in 2004 and his participation in the multi-artist Vote for Change tour a month before the presidential election—divided his fans. Some reacted with overt anger, as detailed in countless Internet postings, while others willfully ignored much of what Springsteen said. As a Republican fan told the Wall Street Journal during the Vote for Change tour, “If he brings [politics] up at a concert, I’m going to boo him—and then I’ll continue to dance.”

For Springsteen, in fact, that tension between the performer seen on the Today show in July 2002 and the partisan figure who denounced the war in Iraq and endorsed John Kerry was only one expression of a fault line running through the center of his art, business, and politics for decades: the struggle with American myths and the ones he’d created for himself. Though Springsteen’s myth—as we’ll see—was an integral part of his success, it became a burden too that he visibly struggled against, particularly after the phenomenon of Born in the U.S.A. As he said in a 1992 Rolling Stone interview, explaining why he’d recently moved from New Jersey to California (an exodus from the ground zero of his mythology that would last for years), “It’s like you’re a bit of a figment of a lot of other people’s imaginations. And that always takes some sorting out. But it’s even worse when you see yourself as a figment of your own imagination. . . . I think what happened was that when I was young, I had this idea of playing out my life like it was some movie, writing the script and making all the pieces fit. . . . But you can get enslaved by your own myth or your own image.”

And in his politics, also, Springsteen was painfully aware of the allure and dangers of myth. As early as 1984, at the height of his own iconic status, Springsteen recognized the power of myth in Ronald Reagan’s landslide reelection. As he told Rolling Stone in December 1984, “I think [Reagan] presents a very mythic, very seductive image, and it’s an image that people want to believe in. I think there’s always been a nostalgia for a mythical America, for some period in the past when everything was just right. And I think the president is the embodiment of that for a lot of people. He has a very mythical presidency.”

Twenty years later, in his speeches at Vote for Change concerts or at rallies for John Kerry only days before the 2004 election, Springsteen would inevitably follow an affirmation of traditional progressive values—“The human principles of economic justice . . . an open American government unburdened by unnecessary secrecy . . . a sane and responsible foreign policy”—with a call for a more honest perception of American history. As he said at the finale of the Vote for Change tour in Washington, D.C., on October 11, 2004, using the same ideas and expressions he’d repeated since early August and would continue to use until Election Day: “America is not always right—that’s a fairy tale for children. . . . But one thing America should always be is true. And it’s in seeking her truth—both the good and the bad—that we find a deeper patriotism, that we find a more authentic experience as citizens, and we find the power that is embedded only in truth to change our world for the better.”

At one level, in the specific political context of late 2004, this call for truth was a direct response to the questions that had been increasingly raised about the Bush administration’s justifications for the invasion of Iraq. It was only an extension of the demand for accountability Springsteen had urged his audiences to make at the end of The Rising tour. But when he expanded on these ideas in National Anthem, a documentary about the Vote for Change tour that preceded the broadcast of the tour’s finale on the Sundance Channel, he spoke directly again about the dangers of myth: “The Republicans have gotten very, very good over the years at selling the myth of America. If you’re not careful, you’ll settle for the dime store version of that, and it’s a compelling story. Everybody wants to believe the president is strong and wise and the country is right and stands by its commitments. These are powerful, powerful myths, you know, because, hey, I tell ’em to my kids at night. But when you’re grown up, America’s not necessarily always right, but it’s supposed to be always true . . .”

Springsteen had seen firsthand how the power of myth could be harnessed. As he ascended to the height of his fame in the ’70s and ’80s, he’d collaborated in his own myth-making. His breakthrough album Born to Run in 1975 had mythologized his own experience in songs filled with desperate young people—“Tramps like us”—dreaming of escape, in an operatic production style that stacked layers of guitars and keyboards and vocals, and even in its graphic presentation. From the cover image of Springsteen as a street punk in black leather to the singer’s declaration in the first song, “Thunder Road,” that “I got this guitar / And learned how to make it talk,” we’re immediately encouraged to cast a romanticized image of Springsteen as the protagonist of many of the songs. And in the final song “Jungleland,” playing rock ’n’ roll itself is a life or death endeavor: “Kids flash guitars just like switchblades hustling for the record machine.” As even a critic as resolutely unsentimental as Lester Bangs would note approvingly in his review of the album in Creem, “Springsteen’s landscapes of urban desolation are all heightened, on fire, alive. His characters act in symbolic gestures, bigger than life.”

As a performer too, Springsteen’s persona was larger than life, his concerts— fraught with symbolic gestures, not the least of which was their sheer length—routinely exceeding three hours. In a 1978 Rolling Stone profile, when Dave Marsh asked him “why the band plays so long,” Springsteen suggested that the length and intensity of his concerts were moral statements. “It all ties in with records and the values, the morality of the records. There’s a certain morality of the show and it’s very strict,” he said. As he’d explained in another ’78 interview, he felt an obligation to honor the sacrifices of his audience who “work all week and a lot of times wait in line for ten hours or some incredible amount of time. . . . They don’t take it lightly, so you have no right to either.” In fact, much of the symbolic quality of his performances was about that bond with the audience, from his dive into the crowd early in the set to the way he would, at key moments, hold up his guitar in salute to the audience, as if, in the words of music critic Paul Nelson, writing in Rolling Stone in 1978, “it were some communal instrument of magic, something which he alone does not own.”

If a myth is a type of narrative that enacts a set of meanings held in common by some group, whether that group is bound together by something as vast as national identity or as particular as a fan’s passion, then the myth that Springsteen offered to his audience throughout the ’70s and early ’80s presented a heightened version of their own lives. For many of his fans, Springsteen’s rise from working-class roots served as a kind of parable of escape and transformation—a parable enacted on stage night after night, its impact felt viscerally in that moment of collective release when the opening chords of “Born to Run” or “Badlands” inevitably brought the crowd to their feet. In a similar fashion, the interplay and community of The E Street Band reflected an idealized notion of friendship that the audience could aspire to as well. As Springsteen acknowledged in his induction speech into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1999, speaking specifically of Clarence Clemons, his African American sax player, but expressing ideas that surely reflect the collective presence of The E Street Band as well, “For fifteen years Clarence has been a source of myth and light and enormous strength for me on stage. . . . Together, we told a story of the possibilities of friendship. A story older than the ones that I would write. And a story I could never have told without him.”

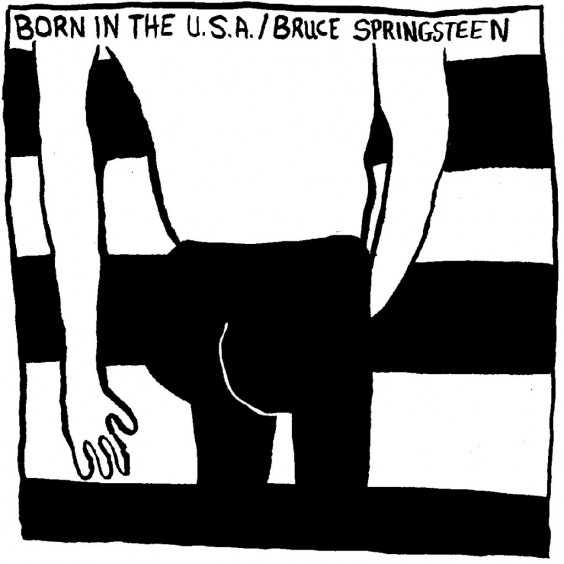

But the myth that Springsteen and The E Street Band enacted became the foundation for something bigger—and more ambiguous—in 1984, when three forces converged: Springsteen’s deliberate decision to reach for a mass audience with an album that, as he would tell Dave Marsh, made “a loud noise”; Columbia Records’ aggressive marketing plan; and the mood of the country as Ronald Reagan campaigned for reelection and declared that it was morning again in America. In particular, all the patriotic imagery of Born in the U.S.A.—from its famous cover image with Springsteen’s newly toned and blue-jean-clad rear end in front of an American flag to the huge flag that hung behind the band on tour as part of the stage set—suggested to many that Springsteen was an icon of nationalism: in the words of one fan quoted in Rolling Stone, “exactly what America’s all about.”

To be sure, the actual content of Born in the U.S.A., in which celebration always teeters on the edge of loss or imprisonment, was a lot more complicated than that. Moreover, both Springsteen and Andrea Klein, who designed the album cover for Born in the U.S.A. and the covers of five of its accompanying singles, insisted that the use of the flag in the album’s imagery was, in Klein’s phrasing, “coincidental.” “[T]he title of the song is ‘Born in the U.S.A.,’ Klein said in an interview with the Springsteen fan magazine Backstreets, “and that’s where it came from.” But as Springsteen acknowledged to Marsh, “the flag is a powerful image, and when you set that stuff loose, you don’t know what’s gonna be done with it.”

In later years Springsteen made no apologies for seeking a mass audience, even as he recognized its perils. As he wrote in the collected edition of his lyrics, Songs, in 1998, “My heroes, from Hank Williams to Frank Sinatra to Bob Dylan, were popular musicians. They had hits. There was value in trying to connect with a large audience. It was a direct way you affected culture. It let you know how powerful and durable your music might be. But it was also risky and forced you to confront your music’s limitations as well as your own.” For Springsteen, at least one risk was that the myth of Bruce Springsteen as an iconic figure, as an everyman who enacted and affirmed the aspirations of his audience, as some vague patriotic emblem—in short, a “dime store version” of himself—would overwhelm a more complex reality in his art and in his life.

Ironically, Springsteen’s vision as an artist was deepening even as his image as a performer was becoming simpler. In the late ’70s, as Springsteen began exploring literature and film seriously for the first time in his life, his songwriting began to change. “I think I’d come out of a period of my own writing where I’d been writing big, sometimes operatic, and occasionally rhetorical things,” he explained in a 1998 interview with Will Percy for DoubleTake magazine. “I was interested in finding another way to write about those subjects, about people, another way to address what was going on around me and in the country—a more scaled down, more personal, more restrained way of getting some of my ideas across.”

At one level, Springsteen’s songwriting began to feature a kind of “small detail,” as he explained in Songs, like “the slow twirling of a baton” in the title song of Nebraska, his acoustic album from 1982. But in rejecting a larger-than-life, “operatic” approach, he also turned to a way of writing in which recurring themes and images were seen from multiple perspectives over the course of an album (and sometimes even within individual songs)— an approach that was less mythic, less an expression of some collective idea or emotion than the novelistic exploration of colliding and contrasting points of view. So, for instance, on Nebraska, the serial killer Charles Starkweather’s embrace of “a meanness in this world” in the title song jostles alongside another character’s insistence on the responsibilities of family as the core of an ethical life in “Highway Patrolman”—“Man turns his back on his family, well he just ain’t no good”—while Born in the U.S.A. contains both the blithely happy-go-lucky speaker trading off his buddy’s “union connection” and hoping to find a good time down south in “Darlington County” and the somber father of “My Hometown” surveying the ruins of a postindustrial America.

Nowhere is this approach more important than on The Rising. Of all the things that an album about September 11 could have been—rhetorical, bombastic, sentimental—The Rising is at once remarkably restrained and expansive in its reach. Except for the opening lines of “Into the Fire,” it makes virtually no direct reference to the event that inspired it, and Springsteen’s lyrics are largely stripped of the “small detail” that evokes character and setting on other albums. He offers instead oblique, poetic imagery—“Red sheets snappin’ on the line” to suggest the imminence of war in “The Fuse,” for instance—and a collage of different perspectives, all rendered with the broadest sonic palette of his career up to that point (Beatlesesque strings, blues guitar, techno-affected drum loops and synthesizer bleats, soul and gospel–styled vocals, even Pakistani vocalists chanting traditional Sufi music). Over the course of The Rising, we hear survivors, mourners, bystanders, terrorists, and the dead themselves. Indeed, for all of the hype that surrounded the album’s release, in spite of whatever it might have seemed to be when Springsteen debuted three songs on the Today show, The Rising is in fact a subtle and vibrant work—and, in ways that are never didactic, a political one too.

Consider, in particular, the movement near the end of the album from the title track, which might initially sound like another of Springsteen’s soaring anthems, to the quieter song that immediately follows it, “Paradise.” If “The Rising” adopts the voice of a speaker from beyond the grave, who may have died in the World Trade Center on September 11, reluctantly letting go of “a dream of life” and embracing a “Sky of fullness, sky of blessed life,” “Paradise” offers two starkly different visions of an afterlife. At the beginning of the song, the promise of a glorious reward after death tempts a young suicide bomber, and then in the third verse we shift abruptly to another speaker in “The Virginia hills” who dreams of seeing a dead lover or spouse—perhaps someone killed in the attack on the Pentagon—“on the other side,” a distant figure whose eyes are not peaceful, but “as empty as paradise.” Over the course of these two songs, in ten minutes and nineteen seconds of music, these voices echo against one another so that no single vision of paradise—a source of “blessed life,” a violent temptation, an empty “void”—can seem definitive.

Though The Rising may have seemed apolitical, the very juxtaposition of these points of view and the refusal to choose between them was itself a political act. In the summer of 2002, not long after the President of the United States had announced to the world that “Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists,” Springsteen envisioned a world of shifting boundaries and perspectives in which such implacable certainties couldn’t be sustained. Even the lines from “Empty Sky” that drew cheers on The Rising tour with their seeming call for vengeance could as easily evoke the loss and anger of a speaker in the Islamic world as an American reacting to September 11. There are no specific references to the nationality of the speaker, and the lines “On the plains of Jordan / I cut my bow from the wood” suggest at once a biblical wrath and the very real tensions of the contemporary Middle East. And in “Paradise,” too, when Springsteen—that icon of America—takes us inside the perspective of a suicide bomber in the very instant before detonation, he refuses to demonize her or him. As Springsteen repeats the line, “I hold my breath and close my eyes,” singing in a hushed, taut voice over a wash of acoustic guitar and snythesizer, we feel the speaker’s fear and anticipation and desperate belief in the rightness of his or her act—and in recognizing those emotions, we have to recognize the speaker’s humanity too.

Looking back at the apotheosis of Springsteen’s fame after the release of Born in the U.S.A. in 1984, the critic Elizabeth Bird, in one of the first important scholarly articles about Springsteen, “‘Is that me, Baby?’: Image, Authenticity, and the Career of Bruce Springsteen,” suggested that the marketing of Springsteen’s image converged with other images of the time—Ronald Reagan’s reelection campaign, car commercials featuring imitations of Springsteen, patriotic celebrations of the Olympics or the reopening of the Statue of Liberty—to create “a potent, swirling brew of images and emotions, upon which people could inscribe any meaning they liked, or no meaning at all.” By contrast though, twenty years later, when Springsteen spoke out against the Iraq War from the concert stage and took an explicit partisan stance in a presidential election, he effectively defined his image on his own terms at last. It was no longer quite so easy to see Springsteen as some vague iconic figure who “brings us together.” On one level at least, in his politics, Springsteen had eliminated any ambiguity. And in doing so he seemed liberated afterwards, too—a different kind of performer and public figure.

Perhaps that was one reason why after the 2004 election, in his fourth decade as a songwriter and performer, Springsteen entered one of the most varied and productive periods of his career. With four albums of new material released in five years; a solo tour; a tour with a band of up to nineteen members that featured acoustic instruments, horns, and gospel singers for The Seeger Sessions in 2006; two tours with The E Street Band; and appearances at the 2009 Super Bowl and on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to celebrate the inauguration of Barack Obama, Springsteen was more active and prolific than ever before. And he was more daring as an artist than ever before, too. From the stripped down and radical sonic textures of his solo tour for Dust and Devils in 2005—singing through the harmonica mic, accompanying himself on guitar, acoustic and electric pianos, pump organ, banjo, and ukulele—to his reinvention of the folk tradition for The Seeger Sessions project to the lavish pop productions of his albums with The E Street Band, on Magic in 2007 and Working on a Dream in 2009, he entered new territory as an artist, producing the most mature and complex work of his career.

Springsteen was also a looser presence onstage and in his public statements. On the Dust and Devils tour, in particular, he’d regularly talk about the artifice of his own image. “I’ve done pretty well with the whole humble bit,” he said, for example, in Minneapolis in October 2005, “and I’m going to be sticking with that for the rest of my career.” And in a letter published on July 31, 2005, in the New York Times Book Review, in response to a review of books about him that reprised many old myths, Springsteen was even more definitive: “The ‘saintly man of the people’ thing I occasionally see attached to my name is bull[shit] . . . Life, art, and identity are, of course, much more complicated. How do I know? I heard it in a Bruce Springsteen song.”

But though he seemed relieved of the burden of his own myth, Springsteen still visibly grappled with larger American ones. In a new song “American Land,” introduced midway through The Seeger Sessions tour and then played at the conclusion of every concert afterwards (through three different tours with both The Sessions Band and The E Street Band), he sang in the voice of an immigrant bedazzled by a myth of America. “There’s treasure for the taking for any hardworking man,” Springsteen would exclaim over a furious Irish jig. Yet for all of this speaker’s expectations of “diamonds in the sidewalk” and “gutters lined with song,” the mythic visions that intoxicate him are only one perspective. A few verses later, another voice is heard, looking back on the immigrant experience through the lens of historical fact, not myth: “They died building the railroads worked to bones and skin / They died in the fields and factories names scattered in the wind.” And with no let up in the music, myth and history come crashing together, infusing the song with even greater energy: celebration, lament, and protest all at once.

Yet even as he acknowledged the darker truths of history, Springsteen still couldn’t simply dismiss American myths either. In the anthemic “Long Walk Home,” the penultimate song of the 2007 release Magic, an album steeped in dread and anger at deceptions that are both personal and political, the mythic images of some quintessential American town have been corrupted. Faces on the street are now “rank strangers,” the diner on the corner is “shuttered and boarded,” and the words the speaker remembers his father telling him shimmer with loss: “You see that flag down at the courthouse? / It means certain things are set in stone / Who we are, what we’ll do, and what we won’t.” But if a return to American values can only be achieved by “a long walk home,” the home Springsteen envisions here is an America that exists at least partly in myth. The town in the song, where “everybody has a neighbor / Everybody has a friend,” is certainly not Freehold, New Jersey, where Springsteen grew up—a town where, as he told Nicholas Dawidoff in a 1997 profile for the New York Times Magazine, “they didn’t like you if you were different.”

Indeed, for all of its perils, myth for Springsteen also still remained a source of hope and inspiration. If in the 2004 presidential campaign he warned about the exploitation of American myths, Springsteen repeatedly evoked a different kind of myth when he endorsed and campaigned for Barack Obama in 2008. “I continue to find everywhere that America remains a repository for people’s hopes and desires,” he said at a rally in Cleveland on November 2. “That despite the terrible erosion of our standing around the world, for many we remain a house of dreams.” For Springsteen, the myth of what America might be was an essential element in the struggle to achieve and preserve “our house of dreams.” So in 2008, on the verge of a potentially transformative election, he could evoke hope, myth, and perhaps even a hint of his own experience in a single statement: “I want my country back, I want my dream back, I want my America back.”

And for once perhaps, for a while at least, it all seemed possible.

MICHAEL KOBRE’s critical writing and fiction have appeared in TriQuarterly, Tin House, West Branch, and other journals. He’s the author of Walker Percy’s Voices. He teaches literature at Queens University of Charlotte in North Carolina and serves as an On-Campus Director of the Queens Low-Residency MFA Program in Creative Writing.

GEOFFREY HAMERLINCK is an illustrator and animator, as well as an instructor at St. Cloud State University.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig