by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Rescue Press, 2017 | 240 pages

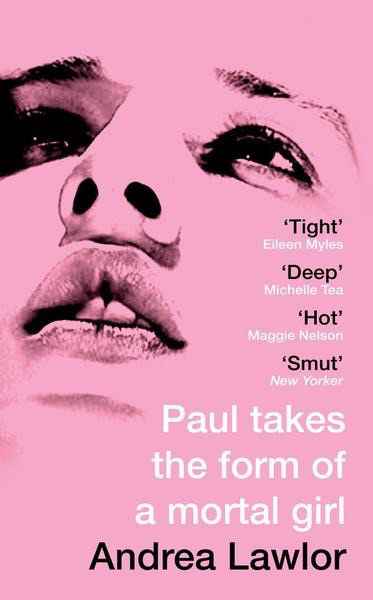

It would be possible to read—as some have—Andrea Lawlor’s stunning novel Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl as an invocation of a sexy and transgressive queer past.

After all, a story that older queer people sometimes tell about their millennial counterparts is that they—we—worry too much about sex. Or, to put it more precisely, we worry about sex in the wrong ways. Too young to remember the riots or the bathhouses of the sixties or seventies, we instead demand affirmative and enthusiastic consent from each encounter, trigger warnings on every obscenity. We punish what older queers might consider merely a wink, a pedagogical flirtation, a flair for the intimate and dramatic. In this generational – and, one might add, primarily white and male – metanarrative, the youth are too sensitive to imagine the primal sexual world of hazy late-night hook-ups, experimental excess, of lawless connection, of bodies and pleasures, that supposedly constituted queer sexuality in its radical heyday. Real queer sex, this story goes, is unsafe.

In contrast with today’s purportedly prudish youths, Paul’s titular character is a 22-year-old who occupies an early-1990s queer world of sexual chase, cruising and crushing his way through his adopted cities of Iowa City, Provincetown, and San Francisco. The coffee shop, the bar, the record store: all are sites of erotic possibility, each counter-transaction or sly smile an opportunity. Paul hooks up beneath docks, in parked cars, in restrooms, each exchange detailed by Lawlor’s hot, fleshy prose. These encounters, needless to say, rarely involve a verbally-expressed “yes.” Furthermore, Paul possesses an unusual, even supernatural, ability that makes his erotic world even more expansive: he is a shapeshifter who can transform his body from shrimpy twink to muscle queen; who can, through sheer force of mental exertion, turn his penis into a vagina and sprout breasts. When he tires of the gay house party or the leather bar’s backroom, Paul becomes Polly and enters other playscapes: the notoriously cruisy—and notoriously trans-exclusionary Michigan Women’s Music Festival, for example, where Polly can have sex not in a dirty men’s room but in a wooded campsite, or the Provincetown lesbian collective house where sex can take place between “plates of vegetarian lasagna or tofu curry.” Polly does a lot more processing than Paul, for sure, but it’s all still pretty sexy.

Indeed, in Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl, Lawlor conjures a stunning, sexually anarchic fantasy. But just as Paul is not just one person, Paul is not just one novel. And just as fantasy is not mere indulgence and wish fulfillment, but is also a way of processing and managing pain, Paul’s invocation of an ostensibly utopian free-loving queer ‘90s also manifests as an entirely different type of story: a raw reckoning with HIV and AIDS.

Despite Paul’s supernatural capacities, Paul is not at all a timeless tale. Instead, it is set firmly in 1993, in the middle of the AIDS epidemic, three years before scientists discovered how to – via protease inhibitors – prevent viral replication, and thus offered the chance to extend life for some seropositive people. The world of Lawlor’s novel is a world in which queer death is common, in which the infected decline rapidly, brutally. As for Paul, he is still a child when the crisis erupts; his stealthy high-school hand-jobs reveal only passing familiarity with the larger world of queer life, and queer death. When he heads to New York City for college, however, Paul stumbles into the world of AIDS activism, having followed a cute boy named Tony Pinto to an ACT UP working group, to “Monday night meetings in the belly of the whale.” At these meetings, Paul absorbs how ACT UP confronts the Bush administration and the pharmaceutical industry; learns how to distribute condoms and teach safer sex, how to stage theatrical protests, how to mourn militantly. Instead of dates, Tony and Paul go to meetings, listen to “the incomprehensible reports from the Treatment Action Group [the committee within ACT UP focused on medical research advocacy] and the group’s incomprehensible response,” what Tony Pinto called ‘the grown-ups fighting.’” In other words, Paul’s whole queer world is the world of the emergency.

By building a novel around a protagonist who is still young in 1993, Lawlor’s novel is able to articulate a form of queer sexuality that is indelibly defined by AIDS. For Paul, there is “relief to be so young, his nineteenth year a talisman, the word containing the word teen itself protection from what the older guys, those memorial-weary men in their twenties, thirties, forties, what they were losing--.” Too young to have been in the baths / bars / backrooms of the previous decade, he is likewise too young to have transmitted the disease before anyone knew what it was, what it would do. His very youth means that he has no adult erotic identity outside of these dying men around him, only slightly older than himself, those “grown-ups” who fought at meetings, these cut-off sentences. What he imbibes from this scarred generation becomes indelibly a part of his understanding of his sexuality – both their nostalgia for sexual activity without what Lawlor describes as “this subterranean crust of fear,” and the devastation that the plague brought upon the community – and informs the psychic geographies of the novel.

When Paul receives word that his first love Tony Pinto has gotten sick, the brew of forces – adolescent desire, terror of the plague, and worry about safe-enough sex – that comprise his psyche propel him down a path of incessant motion. He first flees from New York to Iowa, a place where, he believes, “no plague could find him.” Paul’s Iowa City is a queer place, for sure, but not one where die-ins and meetings are the center of the gay social calendar. When Tony starts calling, leaving messages on Paul’s answering machine, Paul ignores him and lights out for a long weekend in Chicago, where he swells his biceps and submits to rough anonymous sex in a scene in which Lawlor notes, repeatedly, that both men are wearing condoms. Later, Paul – as Polly – goes to the Michigan Women’s Musical Festival, meets a woman, and starts having sex as a lesbian. Even then, her thoughts wander to infection, worrying that she “would be in trouble if the safe-sex people knew they licked each other without dental dams, used latex gloves only occasionally,” wondering if one could “get something from swallowing female ejaculate.” Eventually, Polly moves to Provincetown with her girlfriend, adopts lesbian sexual ethics, pretends to become a vegetarian, and buys a new dildo when her girlfriend thinks Polly’s black one is too exoticizing.

When Tony’s messages get forwarded to Polly by mail, Paul flees again, this time to San Francisco.

By the time Paul makes it to the Bay, it takes tremendous quantities of alcohol to blot out the blinking light of ignored messages on the answering machine. As the novel’s opening line states, “like a shark, Paul had to keep moving.” The motif of Tony’s unanswered messages, following Paul from city to city, reveals that Paul’s rapacious sexual energy is not merely polymorphous desire, but also a flight away from death. Paul’s incessant movement is both towards sex and away from it; he is both shark-like sexual hunter and plague refugee. He is, in other words, traumatized.

It is in San Francisco – that primal sexual world of hazy late-night hook-ups, experimental excess, of lawless connection, of bodies and pleasures –that Paul's queer utopian fantasy can no longer substitute for reality. When Paul, drunk, fucks his co-worker, a trans guy named Franky, without a condom, he goes “cold with shame” and can’t face himself after. In an act that reads both as self-punishment and, finally, an acknowledgment of the inescapability of his own trauma, Paul finally listens to his messages. This time, it’s Tony Pinto’s mother on the tape; Tony has just died, asking in vain for Paul. Paul, finally, lets himself feel what has happened, understand what he’s been fleeing from. As the novel ends, Paul is on the move again, but this time less frenetically. He is just walking around the city, feeling oddly light, neither fugitive nor in chase. Perhaps, Lawlor implies, he is on his way towards a type of uneasy recovery.

In this way Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl problematizes a strain of queer sexual nostalgia that foregrounds erotic fantasy and minimizes its origins in historical pain. By novel’s end, Paul, who has traveled the country searching for ways to have sex that will not reactivate the scarcely-submerged terror of Tony’s impending death, has no choice but to integrate both terror and pleasure. He has learned both from his ACT UP elders and from his own life experience that sex can hurt, can even be deadly, and is grappling with how to find sexual joy in the midst of that pain.

Lawlor’s protagonist, then, does not represent an idealized queer past. Instead, Paul is part of a generation whose sexual maturity brought both a dream of erotic risk and a hyperawareness of its consequences. Likewise, the generation that came after Paul’s, my own, has its own modes of joy, pleasure, and spontaneity, and has also had to forge them in the shadow of the dead. If there is such a thing as a generational sexual ethos, then ours is much more like that of the mature Paul at novel’s end: what our critics see as whining or weakness is better understood, then, as our queer inheritance. Our desire to articulate enthusiastic consent, to combat sexual racism, or to seek justice for sexual harassment does not mean we couldn’t cut it in Paul’s cool cruisy world; I suspect, actually, that we and Paul would have a lot in common.

As Paul discovers, however, constructing a sexual culture out of this fusion of risk and safety takes work. It requires acknowledging that all of us as queer people have inherited a history of sexual hurt—and that we can build out of that trauma something weird, new, and (yes) still perverse. What’s more queer than that?

Cassius Adair is a writer and radio producer living in Charlottesville, Virginia. More of his work is at cassiusadair.com.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig