by Killian Quigley

Published by Nightboat Books, 2011 | 632 pages

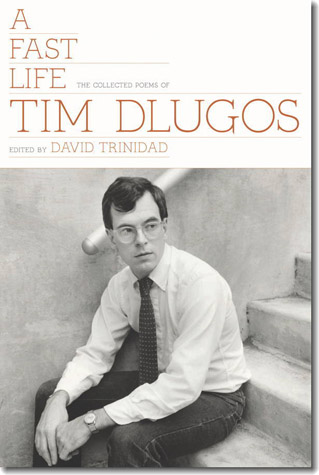

Over the past decade, American poetry may have been luckiest in the patience and devotion of its editors. Writers whose receptions have been limited to regional or aesthetic camps, who have been called poets’ poets, or who have simply faded from view, are suddenly once more in our hands, in collected editions such as Jack Spicer’s My Vocabulary Did This to Me or Jackson Mac Low’s Thing of Beauty. In 2012 we can expect an edition of Joe Ceravolo’s poetry from Wesleyan. This year, David Trinidad has given us the poetry of Tim Dlugos in a remarkable act of service, bringing together all of the work that the poet published in his lifetime as well as much previously unpublished. The resulting volume is an unexpected pleasure and a testament to artistic perseverance.

For many, Tim Dlugos will be an unfamiliar name. Born in 1950 in Springfield, Massachusetts, he was raised by adoptive parents in self-described “TV-sitcom Fifties normality.” He was attracted early to religious vocation, joining a “Catholic Vocation Club” in middle school and then attending a Catholic prep school run by the Christian Brothers. After graduation, he became a postulant for Holy Orders and discovered, seemingly all at once, sex, drugs, and the Catholic protest movement. He studied at La Salle College in Philadelphia on a full scholarship, began writing poetry, came out, and left the Christian Brothers.

Though Dlugos gradually lost interest in his studies and drifted away from the Church, the habits of spiritual reflection he developed during these years remained. He dropped out of college in 1973 and moved first to Washington, D.C.—where he participated in the Mass Transit poetry scene, a reading series that spawned a short-lived publication—then to New York. He published several books of poetry and struggled with alcoholism. In the mid-1980s, he got sober and began taking classes again. In 1987 he tested positive for HIV and completed his degree. The next year he enrolled in the Yale Divinity School, from which he would withdraw the following autumn, spending time in and out of G-9 (AIDS ward) at Roosevelt Hospital. He died from complications due to AIDS in 1990.

At the beginning of his much-anthologized, winking advice column, “Ave Maria,” Frank O’Hara implores, “Mothers of America / let your kids go to the movies!” Judging by the earlier poems on view in this collection, Dlugos’s mother listened. His poem “Shelley Winters” is pastiche O’Hara—straight out of “Lana Turner has collapsed!”—and riffs on the pop-art fascination with celebrity: “I’m so young and you’re so dumb, it never could work / still I watch you every chance I get and love / you, you’re such a mess.” Marilyn Monroe and David Cassidy, Psycho and The Poseidon Adventure, are the stars in the young poet’s firmament. His writing in this period is alive to O’Hara’s “darker pleasures,” punctuated with exclamation points and hip, shrugging asides.

On the back of A Fast Life, a quote from Ted Berrigan tells us that Dlugos is “[t]he Frank O’Hara of his generation.” It is an odd description—in part because Berrigan, himself a second-generation New York School poet, could very easily have inhabited that role—though not entirely inaccurate. The axis of difference is, more than anything else, that Dlugos read, imitated, and idolized O’Hara, calling him “THE great American / poet and seer of this our century.” Elsewhere, he writes, “the magnificent / OH in his name is what you say / when you’re on the street pretending to be / Frank O’Hara.” An infatuation this complete highlights differences rather than similarities, no matter what surface effects remain to mark the influence. Missing from Dlugos’s work is O’Hara’s affinity for surrealist and expressionist modes, his strange blend of radicalism and consumerist lust, his mastery of the sentence, his endless cool. The poems have little of O’Hara’s hip melodrama and fall flattest when they aim for that register anyway, like a lovely small-town singer trying on a diva’s octaves.

When the voice of Dlugos’s poems becomes smaller, admits more readily of its insecurities, it gains beautifully. One of the earliest poems in the volume that feels like an achievement, the titular “A Fast Life,” is a sequence of thirty “sonnets,” prosey, fifteen-line strophes that amble through his time in Philadelphia as a student at La Salle College: “my / academic counselor thought I had the wrong / priorities the nun who taught me Renaissance / Painting thought I was a sensitive person / leading a fast life.” The poem is a talking cure, moving through experiments with drugs, an attempt at a heterosexual relationship, political activism, sex with and without love, and it ends, as a talking cure should, with words both strange and revealing:

In these lines, O’Hara’s fascination with fame is turned on its head and analyzed. The entire poem employs this enumerative and paratactic past tense, but at no point is it as stark or hurt as here. Desires nearly relinquished mark the advent of his poetic maturity, and these lines remind me of nothing so much as the conclusion to James Schuyler’s “His Dark Apartment”:I wanted to beliving with Alfred when we both were veryold I visualized our apartment, with manybooks and records I wanted to sleep withMichael, but never did I wanted to establishThe Poet/City Workshop in a storefront onGermantown Avenue I wanted to be living inNew York, near all the famous poets I admiredI wanted to be famous myself and still do

Those last three monosyllables, longing, accusatory, represent a very different aesthetic from O’Hara’s joie de vivre. As Dlugos writes his way through an “I do this, I do that” poetics, the sense of intimacy he achieves comes more to resemble Schuyler or even James Merrill, assimilating the New York School aesthetic to a poetics of confession.How I wish you would comeback! I could tellyou how, when I livedon East 49th, firstwith Frank and then with John,we had a lovely view ofthe UN building and theBeekman Towers. Theywere not my lovers, though.You were. You said so.

But with Dlugos, confession means something rather different from the histrionic self-display of the “confessional” poets of the 1960s and 70s. A brief poetics that begins the volume declares, “Grace, in a very orthodox sense, is my major preoccupation.” Over the course of his career, this preoccupation with grace moves more and more toward the center of his writing, bending his poems into a posture of supplication:

The late poems, in particular, are focused and sharpened by this sense of impending mortality, and they are undoubtedly among the most affecting works produced in response to the AIDS crisis. “G-9,” a tribute to the AIDS ward in which he would die, concludes:Bless me, father. This is my firstconfession: I’m living in the lightat the bottom of a sea of air,everything I need in a place I sharewith everyone. It’s in your hands.(“Healing the World from Battery Park”)

I hope that death will lift meby the hair like an angelin a Hebrew myth, snatch me withthe strength of sleep’s embrace,and gently set me downwhere I’m supposed to be,in just the right place.The lightly enforced trimeter and the single glance of rhyme create in these lines the very sense of fitful gentleness that they request, and as one reads from the nervous posing of the early poems to the ease of the later work, the history of Tim Dlugos’s poetry appears as a gradual accession to grace. In the final poem of the volume, Dlugos declares himself “D.O.A.” His readers will be apt to disagree.

Justin Sider is a PhD candidate in English at Yale University. His poetry has appeared recently or is forthcoming in Boston Review, Bat City Review, and Indiana Review, and his reviews have appeared in Colorado Review and Meridian. He lives in New Haven, CT.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig