by Killian Quigley

Published by Black Widow Press, 2010 | 383 pages

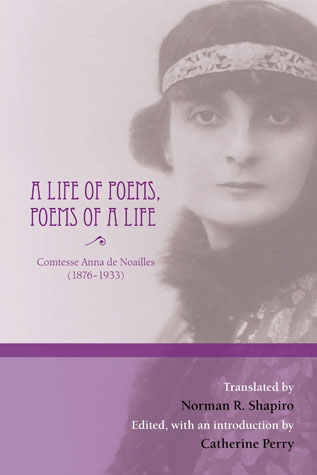

In a lecture on Romeo and Juliet at the New School in the late 1940s, W. H. Auden observed that its lovers’ “union is possible only through their deaths.” This seeming paradox is, for Auden, emblematic of “the secret, the religious mystery, of Romantic love.” Scary stuff, that, but oddly edifying: bereavement may temporarily set lovers asunder, but death can be relied upon to draw them back together at last. Thus the love poems of the Comtesse Anna de Noailles (1876-1933), in which death promises a sensuous paradise, the site of “pleasure, stronger and more harsh than life.” A Life of Poems, Poems of a Life, a commodious new bilingual collection of Noailles’s verse edited by Catherine Perry, reflects a voice that is most ardent and intoxicating when its desire is most frustrated. In her introduction, Perry describes Noailles’s predominant aesthetic as “Dionysian,” and that’s largely true, for these lines are “ecstatic,” “erotic,” and “playful.” But readers will also recognize something akin to Auden’s secret: deeply suspicious of the world, the poet reserves her adoration for the dead.

Noailles’s fantasies are powerfully unsettling gothic romances, rendered in miniature. Impelled by a queerly – and generatively – paradoxical eros, they crave emotional and physical satisfaction from the deceased. Her poetry, which made her “the most popular, the most celebrated, and also the most denigrated female poet in early twentieth-century France,” is “ivre d’éternité” [“drunk on eternity”] and “épris du vide” [“charmed by the void”]. Lost and impossible loves pervade A Life of Poems, Poems of a Life. The poet’s desire is real, but its objects are ephemeral. Her sensuality is acute, but often appeals to the intangible. Motivated by paradox, these poems crave an idealized, deceased beloved, knowing full well that in the moment of attainment, expression and feeling will end. Noailles extols bodily sensation, but associates sensual pleasure with the environment of the tomb and the bodies (corpses) of the dead.

The poems’ other great preoccupation, nature, finds characteristic treatment in “La Querelle” [The Quarrel], from L’Ombre des Jours (1902), the third of nine volumes excerpted in A Life of Poems, Poems of a Life:

Et là, oubliant tout du mal que tu me fais,J’entendrai, les yeux clos, l’esprit las, le cœur sage,Souls les hêtres d’argent pleins d’ombre et de reflets,La respiration paisible du feuillage…

[Forgetting all your hurtfulness, contentIn silvered breeches’ glinting shades, eyes closing,I shall give ear, heart wise but spirit spent,To the calm breathing of their leaves reposing…]

Marcel Proust lauded Noailles for connecting so seamlessly with nature, a feat he thought possible nowhere but in the work of a female poet. Perry goes so far as to argue that Noailles’s Les Éblouissements (1907) significantly informs the guiding philosophy of Proust’s classic À la recherche du temps perdu (1913-27). As Perry explains, Les Éblouissements prompted another contemporary, Rainer Maria Rilke, to translate Noailles, and to admire her capacity to “[reconcile] the self with the external world, most prominently through the body as the subjective seat of nature.”

The “external world” of Noailles’s early poems is amply supplied with gardens, birds, and tombs, but has little room to spare for the human denizens of Belle Époque Paris. Readers attempting to contextualize the prevailing sensibility of “La Querelle” will find little satisfaction in the lines of the nineteenth century’s greatest observer of Parisian life, Charles Baudelaire. To situate Noailles’s mode, we might turn, instead, to the seventeenth-century visions of the English poet Andrew Marvell. In “The Garden” (1678), we encounter an ethos of withdrawal from the chaos of society, and of sensual fulfillment in nature:

What wond’rous Life is this I lead!Ripe Apples drop about my head;The Luscious Clusters of the VineUpon my Mouth do crush their Wine;The Nectaren, and curious Peach,Into my hands themselves do reach;Stumbling on Melons, as I pass,Insnar’d with Flow’rs, I fall on Grass.

Noailles’s poetic subjectivity, like Marvell’s, pulls back from the vulgar details of quotidian existence; she establishes her authority as an observer by avoiding any entanglement with the mundane. Not so Baudelaire’s sticky, heavy, and pulsing poems, which so famously set the stage for French modernism.

But the discrepancy between these poets is not entire: Noailles’s poems, like Baudelaire’s, are mostly conservative in form, expressing themselves through punctiliously-observed rhyming meter. Asked by an interviewer about her formal scruples, Noailles defended them firmly: “La forme traditionelle et la rime sont comme la palpitation générale où tous les cœurs peuvent s’entendre.” [“Traditional form and rhyme are like the general palpitation where all hearts can understand one another.”] Her achievement lies in adapting these forms to idiosyncratic – and sometimes excruciatingly affecting – use. For instance, “Attendrissement” [“Tenderness”] enlarges an image of extraordinary beauty before turning, characteristically, to despair; the pain wrought by this shift is activated, in large part, by the rhyming lines that deliver it.

At times, reading Noailles’s poems can feel like an aesthetically elevated exercise in emotional masochism. The turns to misery are regular, and often irremediable. They issue, frequently – and, in the latter poems, usually – from bereavement. A fairly regular structure is established: the poet is driven to anguish by the loss of the beloved, and in contemplating the loss, is maddened by an retrospective understanding of its inevitability. In Poème de l’Amour (1927), the poet is beset on all sides by emotional traps – to pine for the beloved is to live in anguish, but to forget him is to deny oneself. Occasionally, the poems’ total lack of hope is stupefying, and overwhelmed readers may sympathize with the “bewildered” reception which, Perry notes, met Poème de l’Amour upon its release.

Still, the latter, bleaker sections of A Life of Poems, Poems of a Life also feature Noailles’s best work. Particularly innovative are two meditations on the nature of the soul (“âme”) and its relation to sensual experience. Late in Poème de l’Amour, poem CXXVII boldly declares the soulfulness of the body—in all its feverish heat and tearfulness—over that of “Les cœurs purs et spirituels” [“Hearts pure that ply their soul to us”]. In another rich segment, L’Honneur de Souffrir (1927), the soul is exposed as a dangerous fake, an empty stand-in for the sensual fulfillment obtainable through bodily desire and passion:

XXXIV

Il convient que l’on appelle âmeCet excès de feu, de couleurs,Don’t la jeunesse se réclame. –Mais quand l’arbre perdra ses fleurs,Il faudra bien qu’un jour tu ramesSur la galère du malheur.

C’est le corps qui verse les pleurs!

[XXXIV

We call it “soul” – and well we do –That flaming, many-hued excessOf passion that youth lays claim to. –But when the trees stand flowerless,A galley-slave, one day, will youRoar with your woeful oar. Ah yes!

Flesh, not the soul, weeps its distress!]

Poems like this one negate conventional metaphysics by draining “soul” of its constructed meanings. Their project is not purely negative, however, for they reorient the reader toward a fuller consideration of the body. Bearing her earlier poems in mind, one marks here a significant and satisfying transformation in Noailles’s regard for corporeality.

Poem XXXIV, like many of its kin, is nimbly and imaginatively rendered in English by Norman R. Shapiro, whose translations are set opposite Noailles’s originals. Shapiro’s is an ambitious translation: his innovations are many, his reorganizations bold. This may trouble scrupulous Francophones, but Shapiro’s achievement in hewing to Noailles’s rhyming form, and in allowing the poems to flourish in their new linguistic environs, is impressive. Robert Frost claimed that in translations, “what is lost is the poetry,” and such is often the case. But at their best, Shapiro’s recastings prove that successful translations are like bountiful migrations, which refresh poets’ visions in new and complicated surroundings.

A Life of Poems, Poems of a Life is a necessary work, representative as it is of the contributions of an original voice and formidable figure in French literary history. Its paradoxes will haunt its readers: it is difficult, for instance, to square the anti-solipsistic poem XVII of L’Honneur du Souffrir with a poetic vision which is so often trained inward. Or we might wonder at LVII, from the same group, which reiterates the superiority of the flesh, but resides within a volume that often dismisses the living body for the company of ghosts. But then it is, of course, precisely upon these conflicts and juxtapositions that twenty-first century readers will find most satisfying purchase.

<p>Killian Quigley is an outsized Irish person and hummus <em>cuisinier</em> living in Nashville, Tennessee. He is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at Vanderbilt University, where he reads 18th century Irish and English literature, aesthetic theory, and natural history.</p>

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig