by Deborah Harris

Published by MIT Press, 2016 | 216 pages

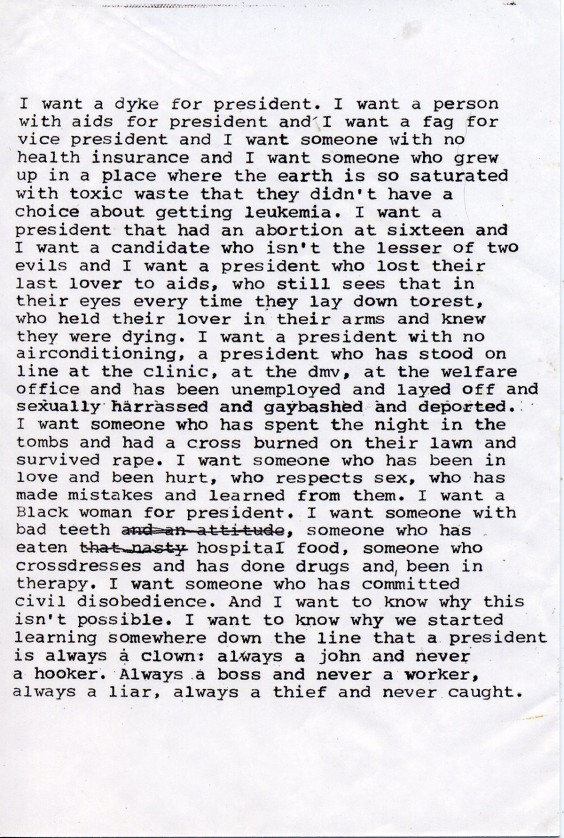

2016 was a digital election. Social algorithms elevated false or misleading information, foreign actors hacked political party digital services, white nationalists surged into a Twitter cadre to troll Black and Jewish writers. A message-board meme featuring a cartoon frog became a national hate symbol. In the aftershock, one surprising image crept through my social media feeds. It was a scanned copy of an old 1990s manifesto from the art-activist group Fierce Pussy:

Over and above the urgency of its radical content, check out the dark smudge on the top edge, the shadow of a crinkle in the bottom right; as if a rebuke to the flurry of news about cyberwarfare, this image retains its homemade aesthetic even when digitized. Even in its predigital form, this was a photocopy of a photocopy, an analog meme.

Kate Eichhorn's Adjusted Margin: Xerography, Art, and Activism in the Late Twentieth Century is a media history and critical analysis of xerography, the reproductive process that made the “I want a dyke for president” flyer possible. Xerography is an unexpected topic for a book on art and activism, in part because the technology was originally marketed as a tool of the white collar worker. Early advertisements for the machines, as Eichhorn describes, focused on the capacity of the machine to replace (female) typists and clerks with Xerox technology, cutting back human capital and helping a “a new managerial class … respond to the ensuing chaos in the manufacturing sector.” In other words, xerography was part of an industrial-age race to reproduce business documents and save labor, and adopted primarily as a tool of corporate life.

Far from a dry account of cubicle life, Eichhorn’s work focuses on how an assorted band of queer and feminist rebels appropriated xerography as a political and artistic form. In centering punks and weirdos as the real power users of the Xerox, Eichhorn’s workis a significant corrective to the cultural history of copying. In Adjusted Margin, xerography is a way to transmit “militant manifestos, smutty gay fiction, DIY guides on how to build your own bombs or grow your own marijuana, and naughty comic books.” With this set of alternative appropriations in mind, Eichhorn brings readers into the office copyroom, but also into the lives of the hourly workers who copied their Riot Grrl band flyers when the boss wasn't looking. Those workers, as well as the queers and outsiders who frequented copy shops, were indeed, as Eichhorn puts it, at the center of the “production and circulation of an entire range of marginal genres, from Xerox art and mail art to fan fiction and avant-garde poetry.” In exploring how workers could commandeer copymachines to make fake employee ID cards or “Silence = Death” posters, Eichhorn shows how xerography enabled alternative artistic genres and organizing tactics.

Eichhorn’s social history approach to media archaeology puts this work in the company of some of the most compelling examples of the genre. The field of media archaeology, building on the genealogical and cultural approaches of Michel Foucault and Walter Benjamin, looks at communication technologies in order to understand their emergence and impact: Jonathan Sterne’s MP3: The Meaning of a Format, for example, traces what was lost and what was gained when music was compressed into digital files, while Lisa Gittelman’s Paper Knowledges: Toward a Media History of Documents reimagines paper itself as a historically-contingent type of ‘media.’ Within this landscape, Eichhorn’s book makes a further critical innovation: imagining the technology of xerography from its most marginal members, rather than its mass impact. By placing protestors and artists as primary actors in her Xerox history, Eichhorn shows how media archaeologies, even of seemingly quotidian technologies, can tell unexpected stories when examined from the margins.

To understand the importance of xerography in today’s political moment, it is critical to understand it not just as a mass-distribution machine, but also as an analog technology. Consider that copy machines today, as Eichhorn points out at the end of her book, are no longer true xerography: they are instead digital scanners and printers retrofitted into the familiar clunky cubes that have long punished office workers. In 2017, copy machines are fitted with hard drives. Unbeknownst to most users, copy machines now keep a coded impression of copied material stored indefinitely, a feature that did not exist when Eichhorn’s subjects were copying their feminist zine or reproductions of their butts. The successor to the technology that empowered Daniel Ellsberg to leak the documents that would become known as the Pentagon Papers, for example, today would almost certainly incriminate the leaker.

It is in this context that Eichhorn notes a curious return to paper in the latter days of the Occupy movement, when activists figured out that “you can flush a photocopied map down a toilet or, if really desperate, check and swallow it—the same cannot be said for a status update or tweet.” As protestors, the press, and other paper-pushers have been branded the “enemy of the people,” it’s no wonder people are finding ways to move their politics offline. Hand-made, non-digital communications technologies like the protest sign and the public meeting flyer seem to have sprung back into life, at least among a particular segment of the political left. From this perspective, the intensely digital nature of the 2016 election might be an exception, not a rule: as even the humble Xerox machine transforms into a digital archive, the analog has resurged as a technique of resistance.

The fundamental strangeness of Adjusted Margin, then, is that it is a work of “media archaeology” that presciently speaks to events that transpired after its composition. Eichhorn, in emphasizing the creative power that artists and activists wrung out of even the most corporate machines in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, could not have imagined that she was anticipating a new wave of analog politics. However, it is possible to read her work this way—as current rather than obsolete— because of its attention to the social. Indeed, Adjusted Margin isn’t merely an archeology of a particular product, but of a set of human practices: adaptation, expropriation, resource extraction, creativity. What Eichhorn’s work makes clear is that queer and feminist activists’ creative appropriation of media technology has endured longer than any single piece of office equipment. Just as the circulation of the “I Want A Dyke For President” flyer pictured above during the 2016 presidential campaign felt, to many of my friends, like a message unaged by the interceding decades, Eichhorn’s book reads not merely as an archaeology of the obsolete – and there is much to be gained from this aspect of the text as well – but also as a polemic for the affordances of analog technologies in these times.

In our contemporary world of surveillance and cyber-warfare, merely imagining reappropriations of analog technologies can be a radical act. Moreover, and perhaps most fundamentally, Eichhorn’s book is a reminder that people on the margins then, as now, have lived and worked simultaneously with and against the technologies and powers of their time, with whatever materials they can make, steal, borrow, or copy.

Cassius Adair is a writer from Virginia. He lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig