by Angela Moran

Published by Wesleyan University Press, 2012 | 314 pages

“You never heard such sounds in your life,” boasts the website of ESP-Disk’, a wonderfully diverse, and perverse, record label that – having weathered a remarkably turbulent career of fits and starts, death and rebirth – is, against all odds, approaching its fiftieth anniversary next year. Such hyperbolic statements have had pride of place in the label’s discourse; a 1966 Billboard ad, reproduced in Always in Trouble , declares, “When nobody else would listen, we opened our minds and our hearts. Where nobody else would go, we ventured. What nobody else would do, we have done.” Entirely the product of the eccentric curatorial practices of its founder, Bernard Stollman, ESP opened its doors on a lark in 1964 with the release of Ni Kantu en Esperanto (“Let’s Sing in Esperanto”), “the first sing along record in the international language… an invaluable learning aid to the linguistically oriented,” a modest exercise intended for the members of the worldwide Esperanto movement – a universal and purposefully apolitical language introduced by Dr. L. L. Zamenhof, a Polish doctor, in 1887 – of which Stollman has been a part since 1960.

Like Esperanto, music has often misleadingly been referred to as a universal language. Yet there was something serendipitous in Stollman’s choice of ESP-Disk’ as the label’s name. The artists he chose, on the one hand, are an uncompromising farrago of avant-gardists with intensely individual voices (the slogan, “the artists alone decide,” is emblazoned on the back cover of all ESP-Disk releases). On the other hand, many of ESP-Disk’s greatest fans have lauded Stollman’s ability to document a kind of musical zeitgeist. As writer Amiri Baraka has said, “it seemed to me ESP was trying to record a trend in the music, what was happening not necessarily in the clubs, but in the actuality of the music.” For a label that allowed its artists unprecedented control over the content of their releases, ESP has had a consistent track record for releasing aesthetically novel and engaging recordings. Such a curatorial achievement is all the more remarkable given the incredible diversity of the label’s offerings, which included anti-war folk-rock groups, the best known of which is The Fugs; the psychedelic pioneer Timothy Leary; a now-infamous “guru,” Charles Manson; and many others.

Nonetheless, ESP is perhaps best known for providing an unfiltered outlet for the new experiments in jazz and improvisation that were taking place in the New York City of the early 1960s, including recordings by Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman, Pharaoh Sanders, and Sun Ra. Ayler, an Ohio-born saxophonist reared on gospel, with his penetrating tone and a wide, heart-heavy vibrato, may be credited with opening the sluice gate, in 1964, with his Spiritual Unity , ESP's second release, a recording now widely acknowledged as a classic of avant-garde jazz (The authors of The Penguin Guide to Jazz , Richard Cook and Brian Morton, gave it a “crown,” marking it as a personal favorite, and placed the record in that volume’s canon, its “core collection”). Stollman embraced Ayler's innovative fusion of abstract improvisation and tuneful composition – his most famous composition, "Ghosts," has been performed by a number of other musicians – and, in so doing, attracted a cadre of like-minded players, fostering a means of channeling the deluge of radical, new music upon a largely unprepared public.

Such unpreparedness likely presaged the decline of the first incarnation of ESP. Though the label's releases were celebrated by a small group of enthusiastic fans, and despite the successes of their more “popular” groups, The Fugs and Pearls Before Swine, the death-knell that is bankruptcy was struck in 1968, just four years after opening for business. Nonetheless, Stollman kept ESP going into the mid-70s, largely through the financial assistance of his parents, who owned and operated a small chain of clothing stores in New York and Vermont. By the time he shelved the record label to find a “real” job, this time as a government lawyer in upstate New York, he had put out approximately 125 records, a tall stack of wax for such a short-lived enterprise.

Though it never completely folded – Stollman has filed taxes for ESP-Disk’ every year since its formation – thoughts of returning to the label as a serious endeavor did not emerge until 2005. Much had happened musically during the intervening years and, happily, ears may be better prepared now than they ever have been to appreciate ESP’s catalog. Recordings by artists such as Cromagnon, an inimitable band of experimenters and pioneers of sound collage, regarded by Andee Connors of San Francisco’s Aquarius Records as “an anomaly, even on the always far out ESP label,” are now being given a well-deserved second lease on life in a world that’s since experienced the harsh sonic assaults of Throbbing Gristle, Wolf Eyes, and others. Since 2005 the label has begun to reissue its original catalog, including previously unreleased archival material, as well as recordings by artists new to the label since reopening, on its website espdisk.com.

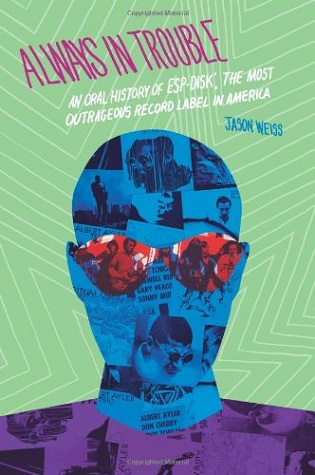

Jason Weiss’ Always in Trouble , the first monograph on this subject, takes a much-needed first step toward unpacking the life, death, and rebirth of this famously uncompromising record label. Weiss’ book, like its subject, is varied, and his use of the oral history genre often favors impressions over conclusions. The largest slice of the book is given to the octogenarian Stollman, himself; in a short introduction, Weiss’ claims that this man’s telling is “the only comprehensive account possible, despite its gaps,” and he is given a quarter of the book’s length to recount his tale. We learn that Stollman received training in law, his “real” profession, because it was the only option open to him; as the first child born to Polish-Jewish immigrants, he was faced with a particularly onerous set of expectations. He recalls, “I had to get a hundred in my exams… it was implicit that I would have to excel.” Despite this, Stollman was bored with his education and indifferent to the establishment. In order to avoid taking the bar examinations, he “allowed” himself to be drafted in 1954 during the armistice following the Korean War. There is a whirlwind casualness to the manner in which Stollman recounts the details of how, following an incident involving segregation while trying to get a haircut, he drafts a report called “Integration of Camp Gordon Barbershops: Reports and Recommendations;” winds up on duty in Germany; is transferred to Paris where he meets a variety of notable characters, including Henry Miller and Richard Wright, and sees a variety of notable performances, including those by Yehudi Menuhin and the Beijing Opera; briefly returns home, to Plattsburgh, New York; travels to Tucson, Arizona, “to check out the region”; and finally emerges in New York City, where he begins a career in law. Whew!

Stollman’s nonchalant voice is at times charming and at times maddening. He relates the bizarre tale of looking up Barbara Streisand’s number in the phone book, calling her, and asking her out on a date, to which see agrees because she happened to be dating a different Bernard Stollman at the time. Our Stollman recollects that he and Streisand “never really got into a conversation.” Or, when Ron Kass, the American business manager for Apple Records, offered him the prospect of releasing an album by John Lennon and Yoko Ono:

“Well, what do you think of it?” he asked. “I haven’t heard it yet, but I have great respect for Yoko as an artist.” There was a brief moment of silence. “Well, John’s a pretty good musician too, you know.” I acknowledged that this was true.The details that he recounts and the short-circuited, blasé manner with which he relays them often seem to want to take us into the realm of the fantastical. Stollman acknowledges that as late as 1960 he had heard of neither Charlie Parker nor Billie Holliday. Within four years (traversed in a mere eight pages of Always in Trouble ), however, he is recording one of the most significant albums of Albert Ayler’s career and flexing his impressively discerning, curatorial muscle, drawing to ESP a slew of talented musicians. With regard to the Sun Ra Arkestra, it was the playing of bassist Ronnie Boykins that clinched the deal. With others, he seems completely impulsive; Archie Shepp, whom Stollman, for all we know, may never have heard play, “stood on the steps outside [the October Revolution in Jazz], puffing his pipe: I invited him to record.”

Toward the end of the 1960s, Stollman’s recollections begin to take on the cloak-and-dagger qualities of a paranoia-induced psychological thriller. In 1968, he attends MIDEM, an international music trade conference in Cannes:

At their reception following the concert [of Marta Kubisová, a popular singer from Czechoslovakia], a young member of [the Czech] delegation approached me and said quietly, “You will come to Prague.” On a hunch, I flew to Prague! ... When evening came, I visited the jazz club and asked for the name of their most celebrated jazz artist. I was told it was Karel Veleny. At my request, they found him for me, and he appeared within twenty minutes. He suggested that we step outside, to avoid prying eyes and ears. We walked out in the darkness, and I said, “I hear you’re the most prominent jazz artist in Czechoslovakia. I have an American label, and I’d like to record you.”The album produced from this encounter, SHQ , did poorly, and orders for the label’s most successful records stopped coming in. What happened? At this point, Stollman’s narrative begins to take on the elements of a conspiracy: he cites, for example, government-sanctioned bootlegging as a means to bleed out the coffers of ESP. Elsewhere he claims that he was wiretapped, and feels that the label’s anti-war stance put them in the crosshairs of the Johnson administration. In Weiss’ interview with Tom Rapp, the leader of Pearls Before Swine, the singer poses another view: “My real sense is that [Stollman] was abducted by aliens, and when he was probed it erased his memory of where all the money was.”

If there is a single central theme to the diverse array of tales told by the interviewees of Always in Trouble , it is money. One of Weiss’ most recurrent questions throughout the book is whether or not the musicians who were on the label, and even those who weren’t, felt that ESP’s royalty payments to its artists were fair. The overwhelming majority, interviewed here decades after the fact, seem less concerned with money and more with the fact that Stollman gave them their first opportunity to get their almost uniformly uncompromising music recorded. Others, however, continue to hold a grudge. Saxophonist Sonny Simmons recalls that, due to money disagreements, “I had to almost kill the guy… I was going to throw him out of the fifth-floor window in his office, because it was open and I was pissed enough to do it.” The most dissenting voices, it should come as no surprise, are the ones that would not participate; while Weiss’ has made a valiant effort to include many of the major characters in ESP-Disk’s history, some, such as Patty Waters and Ed Sanders of The Fugs, didn’t want to be interviewed because they were still too bitter about the finances and their absences, for this very reason, are conspicuous.

Though a crucial topic in ESP-Disk’s history, Weiss’ insistence upon the financial question becomes a tad repetitive over the course of the book. Despite the anecdote relayed by Simmons, as well as another rough-and-tumble encounter courtesy of Sunny Murray where he expresses feeling that his financial troubles with Stollman were unique, that he was his “one victim in life,” the strong emphasis on money comes at the expense of treatment of other topics. Some interviewees, such as saxophonist and composer Roscoe Mitchell, have little to contribute to the subject when prompted, and readers may be left wondering why Weiss doesn’t pick up on this sooner. Likewise, aside from small interjections to provide the name of a song quoted off-handedly, or the name of an album for a track mentioned outside of its context, Weiss makes the presence of his archival research and familiarity with the subject little felt in the interviews themselves. Perhaps most problematically, Weiss seems to want to “set the record straight,” to legitimize Stollman’s own recollections of the label’s history and his financial decisions, which likely influenced the kinds of questions he was interested in asking his subjects. The interviews in the second section of the book, of which there are no less than forty, are sometimes frustratingly short. Readers previously unfamiliar with this incredibly diffuse group of characters may find their distanced recollections all too similar and thus insubstantial, a chorus-in-miniature relegated to commenting on the central and monologic narrative of Stollman.

Still, to those with any familiarity with the subject, the interviews do occasionally provide colorful and revealing anecdotes that bring some of the artists associated with ESP-Disk’ into sharper focus. Gunter Hampel recalls touring with fellow ESP-artist Marion Brown and their respective sons, Ruomi and Djinji, in Hampel’s Citröen, trying to give the boys a glimpse of the ups and downs of the lives of professional jazz musicians. Michael D. Anderson describes his life working as an archivist for Sun Ra. Marc Albert-Levin, a writer, shares stories about his encounters with ESP musicians and the time he spent working as Miles Davis’ cook. Weiss, though a lucid and informed writer, seems to be at his best as an interviewer when he gets out of the way and lets his subjects guide the conversations.

The first of its kind, Weiss’ contribution to the available body of knowledge concerning ESP-Disk’ is a valuable one. Readers who are already familiar with the label’s output and cast of characters will find much of interest in these pages. Those who are less familiar will, largely due to the format of the book, have to work harder to make sense of the story for themselves, weighing each testimony and coming to their own impression, if not a verdict. Nonetheless, all who persevere should find Weiss’ work in assembling this large collection of interviews and photographs – many of which are made available here for the first time – a worthwhile endeavor. If we are lucky, more studies on ESP-Disk’ will follow Weiss’ lead and more questions will be asked of this wonderfully atypical œuvre. Lest we fail to hear the immediacy and urgency of these voices in their time, those who tried to articulate why this music was so exciting in the first place, ESP-Disk’, circa 1966, has implored: “do you know what it’s all about? WHAT IS YOUR FUNCTION? Make it your function to find out.”

Farley Miller is a PhD candidate in musicology at McGill University, where his research focuses on technology and identity in popular music. He is active as an improviser and performer of original compositions with several musical projects in Montreal.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig