by Killian Quigley

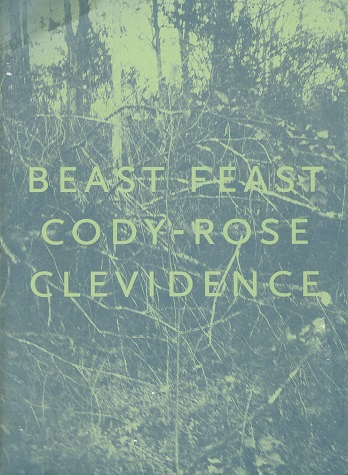

Published by Ahsahta Press, 2014 | pages

“Language is anthropomorphic by its nature and anthropocentric in its assumptions.” That’s Gillian Beer in 1983, writing about Darwin’s long, futile struggle in the 1830s, 40s and 50s to carve out a human language sufficient to convey a vision of nature, of the evolution of species, unpolluted by human form. “Natural selection” is certainly an improvement over than “Mother Nature,” but it still implies the presence of a selector and the will to select; even in the passive voice, saying one species is selected must necessarily beg the question: “by whom?” And then there is that famously problematic word “natural.” What of this world, embodied by the world, evolved from the world, is not in some sense “natural”? Is a posthuman language even possible? Or are we doomed with every utterance to remain trapped within ourselves? Darwin pondered the problem obliquely, carefully, as he glided back and forth in his custom rolling chair and went outside to examine the diversity of the natural world.

Beast Feast, Cody-Rose Clevidence’s first collection of poems, hurls itself at the challenge of creating a posthuman language with feral abandon, striving for a wilderness in language, of language, that might establish for us a vantage outside of language. The poststructuralists called language a “prison-house.” Here it’s more of a prison-garden, with the sublime entanglement of the woods lurking just beyond the hedges.

Beast Feast’s title implies poems about wolves under the moon, feeding greedily on the warm corpse of a rabbit, or bears pawing lackadaisically at a river full of salmon, confident a catch is imminent. But thetitle refers less to the content of the collection and more instead to its form. Beast Feast’s poems are slobbery, bodily affairs, preoccupied with munching and fucking and shitting and puking and “creatural body’s heat.” Sometimes the bestiality becomes a metaphor for rapacious capitalism, describing the undulations of a “daisy-studded nasdaq” or a “fluctuating market economy” that “bows & twirls & spouts & blooms.” More often it is guttural utterance of a non-referential kind, deliberately unattached to meaning; it is grunting, throat-clearing, “the inarticulation before the articulation.” But what really makes the title emblematic is not what it denotes (or connotes) but how it sounds, how it feels as it rolls off the lapping, even bestial tongue of the reader’s imagination. It’s semi-tautological wordplay—two words, almost the same, poised for endless repetition: Beast Feast Beast Feast Beast Feast Beast… It’s a two-word construct that’s highly linguisticdespite the ostensibly a- or pre-linguistic connotations of the words themselves; it’s a construct that approximates beasthood formally, not thematically,by pitching language itself into the cyclicalities of instinct.

The poems constantly attempt to body forth a poetics of animality.Then again, as Derrida reminds us, “animality” is a word which functions to police and pigeonhole the nonhuman for their lack of language. Perhaps we should call it a poetics of bare life, achieved—if it is achieved—through unending experiments in linguistic self-reflexivity. The Ouroboros is the book’s totem animal, the beast in question; in every space of the text, language eats itself and reemerges to eat again, an autophagy “tongue-tied nausea of form.” The question is whether this autophagy—this “tongue-tied nausea of form”—can do anything to get us past the intrinsic cannibalism of language.

And Beast Feast can be read as a series of jagged meditations on the sublimation of the organic into thetechnological, a process the collection evokes on the level of form. Indeed, Clevidence’s poems are distinctly unnatural affairs, artificial, manufactured:

Bestial elements emerge here: “steer,” “stag,” “bullock,” “fetus,” “cunt,” “tulip,” “heart.” But they appear to us locked and framed by structureswithin structures, built from syntax and punctuation—a Palace of Art designed by a schizophrenic or perhaps algorithmic architect. These lines actually do, albeit obliquely, suggest an ecological narrative, a story of the colonization and domination of the wild. “Stag,” crossed out, becomes “steer,” becomes “bullock,” becomes “fetal bull”: the wild animal transformed into the domesticated animal by artificial selection—a process compared by analogy to the taming of the “cunt” by “dysmorphia.” There are oblique references to factory farming and the forest-destroying productions of “TriForest,” a company that specializes (according to their website) in plastic labware, polycarbonate packaging, and outdoor camping equipment; there’s the expression of a desire (a drive?) to be “ungenomed.” Dashes and brackets lacerate the body of the text, making it opaque, monstrous.And yet, it becomes clear in a poem like this that Beast Feast couldn’t exist in a world without code, and probably wouldn’t prefer to. Poems here are “silicon that grows these budding trees”; almost all the poems in the book depend on code not only in that they adopt code-like syntax but also in that their rendering would likely be unthinkablewithout the invisible agencies of Word or Pages or some other human-machine interface. If language is a prison, punctuation and syntax are its torture devices. But Beast Feast demands that we grapple with the idea that there is more to these devices, these racks and chains of { and | , than the subjugation of the living body.STEERAS STAG BECOMES { XEMPT // TRI-FORESTED // LANCED } is silicon that grows these budding trees my heart-mascaraéd “heavens” AS STAGBULLOCK{TULIP} : CUNT IN THE PERSPECVIE | -dysmorphic | OF THE FETAL BULL{ungenome-me (in) the striking (forth)}

The book explicitly indicts empiricism and accessibility with destroying what they would ostensibly parse. “Subject matter” implies things ordered by a subject, for the benefit of a subject; reading pleasure implies things ordered for the consumption and delectation of that subject. As one (rare) couplet puts it, “to see an object is to distinguish / to see an object is to extinguish.” Beast Feast wants to be the kind of object that resists—“syntactically atrocious,” a “convulsive body,” a poetics truly and irreducibly queer. Hence, at a certain point the surface of the text devolves into rows of columns that strain at the limits of legibility (or become illegible, period):

Queerne ssnecessi tatesarad icalizedl anguage basedint hedissol utionofth eboundar iesthatus uallycirc learound conceptsFair enough. If “queerness necessitates a radicalized language based in the dissolution of the boundaries that usually circle around concepts,” punctuation—which is, at bottom, the insertion of arbitrary boundaries between words to make them congeal into thoughts (much as the insertion of consonants between vowels creates words)—can be an agent of that dissolution. So can chaotic formatting; so can Microsoft Word (indeed, one of the most posthumanist things about Beast Feast is that it seems almost co-authored by Microsoft Word).

And yet the above quoted column of text, which could easily function as a manifesto for the volume as a whole, reveals the central irony of Beast Feast: the more strange and opaque a body of text appears, the more likely the reader is to develop a mode of reading that organizes it into a higher form, a meaning or order, dismantling its tactical modes of resistance. The mind is a machine designed for pattern recognition, and regardless of how ‘other’—bestial, feral—the language, the mind will attempt to make sense of it, humanize it. The poems in Beast Feast constantly use esoteric formatting, spatial disorder, and ‘information’ regurgitation—words like “polyhedra” and “prokaryota”; grammars of the dictionary entry and the mathematical function—to blockade themselves against the domestications of an interpreting human subject. But even the most difficult poems in the collection become arranged, semantically drawn and quartered, if you spend enough time staring at the page. Even the most denatured language becomes “natural” language eventually. The resemblances to code only end up revealing a more fundamental, and deeply unsettling, hermeneutic script.Language can indeed be radicalized, stripped bare, made queer, but reading will always seek to tame its bestial excesses into the familiar form of the human subject.

Is a posthumanist language possible? Perhaps in theory; perhaps not in practice. Cary Wolfe has argued that “the nature of thought itself must change if it is to be posthumanist.” Beast Feast ultimately fails, as it necessarily must. It bends and twists the structures of language until the spine breaks and the body spills into new morphologies, new “morphisms” beyond anthropo-; the reader then picks up these pieces and assembles them together again. What the book does succeed atdoing is striving: repeatedly, feverishly, asymptotically. The “stag” to “steer” edit is just one among dozens of moments of explicit self-revision in which the speaker stops, sputters, and tries again; the line “each daisy has the perennial eye of a [the] [nonexistent] god” is an editorial palimpsest containing at least three attempts at expressing the same idea. No poem is the same; each tries some new, radically different formal variation; “feast” is both the word that follows “beast” and, like “beats,” a rearrangement—another try. What would a posthumanist language look like? Probably nothing like any of the pages in Beast Feast. Read—or at least encountered—in sequence, however, the pages of Beast Feast begin to suggest what a posthumanist language would have to keep doing to itself to survive in the wild: erasing, unmaking, forgetting, resisting:

A STATE OF NATURE A NATURAL STATE

Matt Margini is a PhD Candidate in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, specializing in Victorian literature and its animal representations. His writing has appeared in Kill Screen, Public Books, and Victorian Poetry. He often solicits wisdom from a blue crayfish named Papi.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig