by Angela Moran

Published by University of California Press, 2011 | 507 pages

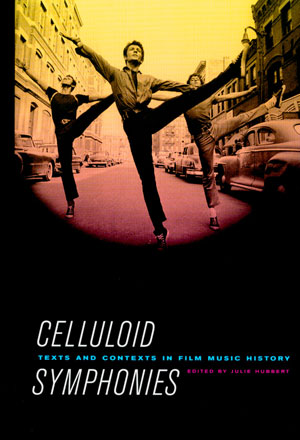

The study of film music, despite its current popularity in both musicology and cinema studies, nevertheless remains a relatively new subject of analysis in both respective fields, and as such has been, arguably, lacking a definitive treatment. While some texts that treat the topic provide a broad overview of historical developments within the film music industry, others touch on its practical / technological processes, and still others deal with the changing theory of the film score. Very few, however, provide all three elements within one source. Julie Hubbert’s Celluloid Symphonies Texts and Contexts in Film Music History, providing just this, is an important addition to this lacuna of film music research.

Structured around the analysis of 53 primary documents, Hubbert’s Celluloid Symphonies investigates theoretical writings, personal interviews, cue sheets, and selections of musical accompaniment, and in the process presents an alternative stance on three leading fields of film music study: music’s aesthetic role in cinema, the advancement of sound technology, and the growing commercial importance of the score.

“Music in the silent film, rather than being a fixed production element, was an ephemeral exhibition piece, and in many ways it was valued for its very lack of mechanization, for its ability to be living, flexible and personal. Music and sound made film not only realistic but also artistic.”

Part I of Celluloid Symphonies, Playing the Pictures: Music and the Silent Film (1885-1925) , concerns the strong correlation between music and the moving image throughout the silent film era. As Hubbert explains, the 40-year span of silent cinema saw a growth in the complexity, length and sophistication of films, which, she argues, is similarly reflected in the musical accompaniment. This increase of musical sophistication was experienced at the time in several different ways, as demonstrated in the contrasting documents of Part I. While some composers and theorists believed that complex, dramatic films required a heavier incorporation of traditional classical works, other individuals, including theater organist Blanche Greenland, believed that such a practice was an affront to the original compositions, and a clear “cheapening” of the classical tradition. Some even suggested, in a fairly radical notion at the time, original themes be composed to accompany the film’s protagonist. By spotlighting these contrasting viewpoints throughout this early age of cinema, Hubbert effectively challenges the common belief that, during the silent era, film music was largely an afterthought.

“Music should participate in the construction of reality, in the sense that it should have a visible source on screen. It should also be carefully placed so as not to interfere with the film’s dialogue.”

Though describing Hitchcock’s stance on the early incorporation of music in film, this quotation, as Hubbert makes clear throughout Part II, All Singing, Dancing and Talking Music in the Early Sound Film (1926-1934) , accurately summarizes the general consensus of Hollywood during early sound films. Indeed, the film industry was uncertain how to effectively incorporate music into film without threatening the desired aesthetic of realism in cinema. Without a visual sound source on screen, producers believed that uncertainties as to the music’s “source” would confound viewers and pull them out of the film’s diegesis.

By tracing this rocky path of film music standardization from the song-saturated musicals to the ascendency of the microphone and advanced recording technologies, Hubbert demonstrates, through both her commentary and selected documents referenced, that this transition to sound was not as seamless as often believed. Instead, while the technological shift was swift, there was also significant hesitation preceding the transition, as well as a surprising resistance following the change. Noting not only the opposition of directors, “Einstein, Clair, Vidor and Chaplin,” but also the steady, continued attendance of silent films following the introduction of sound, Hubbert convincingly disputes the common misconception of late 1920s cinema – that The Jazz Singer killed silent films.

“It was the cinema’s mass appeal, its ability to engage multiple demographics and age groups, that helped it generate record attendance figures that by most estimates represented a third of the country’s population. Even as the country was plunging into a great economic depression and industries and businesses nationwide were suffering crippling losses and foreclosures, the film industry enjoyed relative prosperity.”

For the majority of Part III, Carpet, Wallpaper and Earmuffs The Hollywood Score (1935-1959) , Hubbert does a commendable job of discussing the many influences on Hollywood’s new “vertically integrated” studio system. Noting the strict censorship of the production codes, the social and political influences of the Great Depression, WWII and Post-WWII, and the technological threats from the invention of the television, Hubbert explains how Hollywood not only triumphed over the period’s many significant challenges, but did so with considerable success. These struggles, of course, inevitably brought about changes in the industry, especially with the approach to film scoring. While Hubbert notes several factors impacting music’s changing roles, she focuses largely on the influence of WWII in its gradual darkening of films “to accommodate more somber, realistic material.” She argues that film composers began questioning whether their current techniques of composition were appropriate for cinema’s more serious tone. While this idea is certainly plausible, one may question her use of Aaron Copland as the primary example. Employing the well-known American composer’s essay, “Music in the Films” as support for her claim, Hubbert argues that Copland found “many aspects of the prewar underscore limiting and in need of revision.” While Copland’s essay certainly questions the standard compositional practice of 1930s and 40s film music, one may hesitate to draw a connection between his own musical output and the increasing realism of WWII films. Indeed, when one considers Copland’s compositional output from the mid 1930s onward, with concert hall, opera, radio, and ballet pieces including El Salon Mexico (1936), The Second Hurricane (1937), Prairie Journal (1937), and Billie the Kid (1938), one quickly observes that much of this lean, more individualized scoring style was already established in Copland’s compositions well before the growing popularity of 1940s war films.

“What was most required of film composers working in the 1960s and early 1970s was a facility with a variety of musical styles and a willingness to explore unconventional instrumentation.”

Comparing Hollywood’s “near death” recession of the 1960s and early 70s to the many insecurities and anxieties of the American public during the same period, Part IV, The Recession Soundtrack From Albums to Auteurs, Songs to Serialism (1960-1977) offers an interesting lens through which to view the many drastic changes within both the film and film scoring industries during the period. By intertwining the discussion of Hollywood’s economic instability with America’s political and social unrest, Hubbert clearly demonstrates the latter’s influence on the industry not only financially, but creatively as well. While directors and producers began catering films to niche markets in the attempt to boost overall sales, composers too started pushing the boundaries of standard “hit singles” production, acknowledging “the commercial value of the entire score when viewed as ‘a collection of hit singles.’” This increased participation of composers in the new “hit” song approach, and in turn challenged standard orchestral scoring as well, encouraging a greater inclusion of current popular styles. Similar to earlier developments in film scoring practice, these new changes faced skepticism and hesitation by older film composers in the industry, including such “veterans” as “Bernard Hermann, Franz Waxman, Alfred Newman, Miklos Rosza, and Hugo Friedhofer.” Unwilling or unable to adhere to the industry's new pop standards, this well-established group of musicians turned away from film composition, providing room for the standardization of these new scoring approaches and sales tactics by composers such as Henry Mancini, Ernst Gold, and Maurice Jarre.

“The videoization of film did more than just increase the distribution of viewership from a reel of celluloid to a multi-formatted ‘film product.’”

Focusing largely on the revolution of marketing and distribution in the industry, Part V, The Postmodern Soundtrack Film Music in the Video and Digital Age (1978-Present) , offers an interesting look at the development of cinema from 1978 to the present. Tagging Jaws (1975) as the film that ended Hollywood’s recession, Hubbert convincingly explains how the influence of “front-loading” distribution, a technique in which Hollywood simultaneously released a film at nearly every theater across America, was particularly effective with such a “high-budget, highly anticipated film,” as it allowed Hollywood to “saturate the marketplace,” rendering substantial and immediate revenues to the industry. Despite this growth in ticket sales, however, Hubbert notes that by the 1990s, box office sales provided only 20% of a film’s revenue, while the remainder fell upon the marketing of memorabilia, soundtracks, and even video games. In fact, a major element in the success of a film, according to Hubbert, is the practice of pre-selling merchandise, especially soundtracks; with the growing dominance of pop music in films, the score’s hit singles permeate the airwaves prior to the film’s release, building excitement and anticipation for opening day.

Closing Part V with a discussion of the latest developments in film music, Hubbert not only notes contemporary pop hits and the incorporation of “world music” within the soundtrack, but also, perhaps a bit more surprising, touches on the relationship between video game and film composition techniques. In fact, Hubbert closes this section not with a discussion of recent film scores, but instead of video game music, noting, “game music has become an established and autonomous genre of music.” Indeed, an interesting relationship has formed between Hollywood and the gaming industry following more recent advancements in video game technology; while video games began looking toward film for techniques in video and sound production, studios similarly turned to video games for story inspiration. Not surprisingly, this convergence of media transferred musically as well, as video games and films mutually influenced scoring approaches, and a demand for game music soundtracks grew. By concluding the text with this brief discussion of the video game industry, Hubbert proposes an entirely different field awaiting careful scrutiny, perhaps through the lens of film score analysis.

With 500 pages of rich, informative text, Julie Hubbert’s Celluloid Symphonies provides both an overview of important and often overlooked documents concerning the aesthetic, technological, and commercial elements of film music, and also a well-argued, alternative stance on the history of the genre. Celluloid Symphonies, with its wealth of information for both students and scholars, is a timely addition to the field.

Paula Musegades is a doctoral candidate in Musicology at Brandeis University, where she is currently writing her dissertation on Aaron Copland’s work in Hollywood Film. Her areas of interest are Film Music and American Music of the 20th century.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig