by Killian Quigley

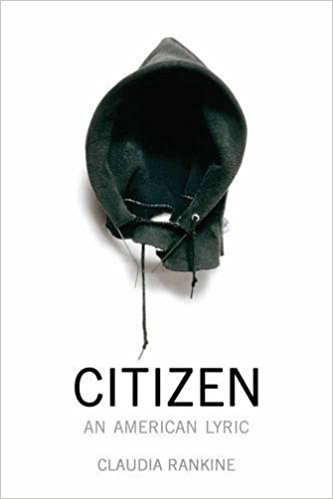

Published by Graywolf Press, 2014 | 160 pages

“When you are alone and too tired even to turn on any of your devices, you let yourself linger in a past stacked among your pillows.” So begins Claudia Rankine’s newest volume, Citizen: An American Lyric, with a line reminiscent of Yeats’s “When You Are Old,” though without the iambic pentameter. Citizen, like Yeats’s poem, interrogates the past, the ways in which memories, or fragments of memories, get “reconstructed as metaphor” and incorporated into who we are. Rankine’s collection documents, in particular, the ways in which misunderstandings, racist speech acts, and myriad other acts of violence are culturally and historically embedded—and in turn become the histories that shape future selves and actions. Such moments, the speaker of Citizen remarks, “send adrenaline to the heart, dry out the tongue, and clog the lungs.” They are discontinuous, uninhabitable, and yet uncanny in their similarity and familiarity: “Each time it begins in the same way, it doesn’t begin the same way, each time it begins it’s the same.”

Although billed as a “lyric,” Citizen is actually the product of Rankine’s deep struggle with the lyric form; it is, as she has said, an effort to “pull the lyric back into its realities.” If, traditionally, the lyric’s territory is that of the first-person pronoun, Rankine opens up the potentially sealed or homogeneous lyric unit to the grammatical and subjective confusion of the second person (the primary figure is designated throughout as “you”). Against the traditional aestheticist notion that the lyric is apolitical, Rankine broadens the lyric’s scope into a space for staging various negotiations between—in Citizen’s words—the “self self” and the “historical self.”

Thematically unified—its question one of intimacy, its fabric the intersection of social and personal realities, its bruising frame one of race—Citizen is formally discontinuous, composed of fragments of essay, academic commentary, lyric verse, and reproductions of the art of Nick Cave, Kate Clark, J. M. W. Turner, and others. Citizen embodies, in this formal disunity, the subjective and interpersonal turmoil that haunts its speakers. With their wide, glossy margins and generous allotment of white space, its pages take on the appearance of art gallery walls—also political spaces.

Much of the volume consists of semi-autobiographical vignettes—blocky, narrative-inclined prose poems told in a measured second person—which depict various acts of racism and disenfranchisement, acts which linger in the mind and expand like a cancerous sore. The primary figure “you” is you, of course, the reader, but also maps closely onto Rankine herself. As she says in an interview, “I made a conscious decision to inhabit my own subjectivity in this book in the sense that the middle-class life I live, with my highly educated, professional, and privileged friends, remains as the backdrop for whatever is being foregrounded.”

In the book’s first vignette, “you” are a twelve year old, negotiating the requests of a white Catholic girl who wants to cheat off your work and a nun, Sister Evelyn, who either “cares less about cheating and more about humiliation” or never, in fact, “actually saw you sitting there.” It’s a scene that, superficially, could be interpreted as reinforcing an easy dismissal of racism as an “anachronistic residue,” to use Rita Felski’s terms. However, as Felski cautions, racist hierarchies are “not primordial remnants of an irrational past, but an integral part of history,” and so of the present. Elsewhere in the volume, an academic “tells you his dean is making him hire a person of color”; a trauma therapist screams at you to “‘Get away from my house!’”; a friend calls you a “nappy-headed ho”; a woman says that she didn’t know “black women could get cancer.” Despite the speaker’s expressions of refusal and dissent, such moments seep all the way down: “You can’t put the past behind you. It’s buried in you; it’s turned your flesh into its own cupboard.”

Even if the “you” often seems to be black and female (Rankine was born in Jamaica and moved to New York at the age of seven), Citizen explicitly challenges this assumption. “And always,” Rankine writes, “who is this you?” It is Rankine, but it is also the media person shaking his head at Serena Williams and her “Crip-Walking” and the white cop who stretches an innocent black man across the hood of his cruiser. Citizen encourages, as Rankine has stressed, the “performance of switching your body out with the body in the frame and moving methodically through pathways of thought and positionings.” It disallows a comfortable formation of identity, instead facilitating an “opening between you and you, occupied, / zoned for an encounter …”

Most of the encounters between “you and you” in Citizen are failures, doomed by the multiplicity of violences (physical, verbal, legal, etc.) which render the self simultaneously “hypervisible” and invisible. “A friend once told you,” she writes, that “there exists the medical term—John Henryism—for people exposed to stresses stemming from racism. They achieve themselves to death trying to dodge the buildup of erasure.” Rankine recounts how someone asked the philosopher Judith Butler “what makes language hurtful”:

Our very being exposes us to the address of another, she answers. We suffer from the condition of being addressable. Our emotional openness, she adds, is carried by our addressability. Language navigates this … Language that is hurtful is intended to exploit all the ways that you are present.

In this telling, selves accrete invisibility, the “weight of non-existence,” via the production of a body made abject. Rankine quotes Ralph Ellison, saying, “Perhaps the most insidious and least understood form of segregation is that of the word.” The painful, dangerous power of the word persists even in scenes of seemingly pure physical violence. In a series of “scripts” that combine text and image included in Citizen, written in collaboration with photographer John Lucas, we encounter the figure of white supremacist Deryl Dedmon and the pickup truck with which he murdered James Craig Anderson: “The pickup truck is a condition of darkness in motion. It makes a dark subject. You mean a black subject. No, a black object.” Here Rankine reads the pickup truck as a figure of speech, one that falls on Anderson’s body with all the weight of history behind it. “You were there,” she writes. “If this is not the truth, it is also not a lie.”

Kelly Caldwell’s writing and art has appeared or is forthcoming in Fence, Denver Quarterly, The Mississippi Review, Phoebe, The Seneca Review, Pacific Standard Magazine, The Rumpus, Guernica, and VICE, among others. She is the winner of an Academy of American Poets University Prize and the 2019 Greg Grummer Prize, judged by Jos Charles. She is the Co-Editor-in-Chief of The Spectacle at Washington University in St Louis.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig