by by Margaret Kolb

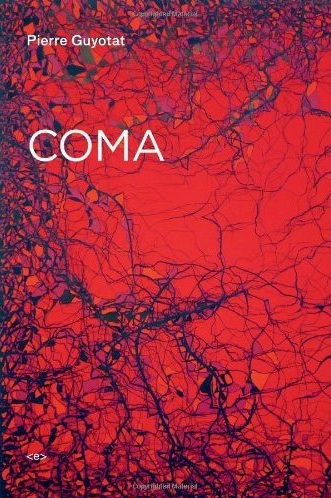

Published by Semiotext(e), 2010 | 232 pages

In December 1981, the French writer Pierre Guyotat entered a coma induced by the harsh rituals of fasting that had become an integral part of his writing ethic. He was 41 at the time, an age “which as a child I had decided never to live beyond.” On the night of December 8, lying in a cot near the door at a friend’s home, Guyotat, whose emaciated condition causes him to chronically slip into and out of sleep, has a dream “in which Beethoven composes and directs pieces from an unpublished quartet: his warm breath surrounds and envelops my head, steam wafts from the remains of dinner on a back table, musicians, the young inside the half-circle, plump cheeks, the older and graying along the sides, play the almost imponderable, silent music that B. hands them from the piano in large sheets that crackle loudly as they touch. The image of the scene blurs as I faint on the chair from which I am listening...”

Incapable, like Nerval, of distinguishing between dream and life, Guyotat draws no hard distinction between his dream of Beethoven and his sudden fall, on the physical plane, from the cot onto the hard tiled floor: “It is within that dream that I feel myself dying, and an angel marks the ground and the bottom of the door with its imprint (its wing). It is morning.” Guyotat’s pained, unsentimental entry into a comatose state, marked by an angel (in that familiar French Catholic perception of the saints and martyrs, who before some divinely ordained extinction, endure a vision of seraphs and thrones gathered around the Cross), delivers him not unto death but unto a hermetic rebirth--one which would produce an account, an Orphic testimony from the Greek underworld, down where the dead converse with and reveal secrets to the living. The blur of the dream-screen blurs in a flashback mode reminiscent of film sequences that transfer from a present chronology to a previous one; in Guyotat’s case, the transfer is from cinematic subjectivity to corporeal objecthood--he is returned to life brutally by the same musical forces that had distracted him from it. Beethoven fades out, along with his unpublished quartet, but the after-image, a multiple and necessarily multiplied one, is vitally retained: that of his externalized body at an intimate remove from the scriptum that constitutes the matière et mémoire of Guyotat’s Coma (2006), a return to memory (to the “I” of memory which Guyotat had so long attempted to fracture and efface in his life and work) and a return to the kinematics of voice, speech, and physicalized language that would rehabilitate his waking back into life, into authorship.

And yet Guyotat’s post coma awakening, though marking no abrupt break with his past, does simultaneously signal a new departure. Guyotat had been marked from his earliest memories of childhood by a commitment to the external, the love for what lies in extremis. The coma state, dawning upon Guyotat as a sun dawns on a hillocked landscape, announced itself as Hamlet’s undiscovered country, as peripheral to life as the white margin is peripheral to the text on the page; as near to death as to approximate it, as to embody its static silenced wave--the speechlessness, the whiteness of the page, that lies before speech, before text. (Guyotat habitually chooses the peripheral space over the domestic or interior: he prefers to sleep in vans, in cots placed strategically near the door of friends’ homes, or out on the street, in the cold, in abandoned factories, in makeshift beds with hobos, construction workers, strangers, brothers, lovers--selfless, he eases into the efflorescent marginalia of spontaneous relationships.) Those unfortunates who slip, or who are violently thrusted, into coma, lacking a physical response system, present to us a partial death, a suspension in the vortex of life-forces. For Guyotat, hunger artist, the coma state acquires the concreteness of destination, a nexus, a crossroads where denotations, material states, meet, collide, intersect.

Coma: “a state of deep, often prolonged unconsciousness, usually the result of injury, disease, or poison, in which an individual is incapable of sensing or responding to external stimuli and internal needs” (American Heritage Dictionary, 4th Edition). But not merely deep sleep, or the simulation of a sleep so deep it scratches at the surface of decay (from the Greek komē). In astronomy, coma signifies the “luminous cloud of particles surrounding the frozen nucleus of a comet; [a nebulous envelope which] forms as the comet approaches the sun and is warmed” (WordNet 3.0). In botany, coma denotes a “tuft or bunch--as the assemblage of branches forming the head of a tree; or a cluster of bracts when empty and terminating the inflorescence of a plant; or a tuft of long hairs on certain seeds” (Webster’s 1913). Coma, then, is not merely the sleep of matter, but the corona or haze that surrounds this sleep, nurtures it, ornaments its body in dream-stuff.

Born in 1940 to the German Occupation (memories of bombs, of his siblings crouching in fear, and of his parents, French Resistance fighters), and later, as a young man, enlisted into the Algerian War (only to be eventually imprisoned and brutally interrogated for allegedly corrupting the morale of the troops), and afterward committed (sometimes by his own family or friends) to psychiatric wards and health clinics, “elud[ing] even the feel of death” became Guyotat’s first and most natural vocation. An erotic kinetics--of the body, of language, against death--moves him, thus, to “nomadize” himself: “To nomadize is to make oneself available to all, to those who are close to us but especially to strangers. It is also to forget the self, increasingly; the self that is the true enemy and that still remains, unfortunately--and for how long--the backing of creation. It is thus easier to enter the economy of human groups if one transports, in one’s work vehicle, the people, and their food and goods.” Yet this same need for mobility, to “nomadize” himself, ineluctably compels him to “hurry toward what’s killing me...only a new situation in a new place, mobile if possible, changing, can bring me peace.”

Aided in his travels, temporarily, by the intake of Compralgyl (a potent analgesic similar in effect to codeine), Guyotat manages to overcome the debilitations caused by malnourishment and insomnia; but eventually, with the side effects of phenacetin carving away at his kidneys, the daily self-prescribed dosage of nearly 100 Compralgyl pills (to which Guyotat has become entirely addicted) takes its toll on his skeletal body. Human connectivity weighs upon him like an albatross: “To refound the self in the place, the time and the state of the human, in the full light of day, and with others around living fully in that light, is perhaps natural for humans attuned, but is a vain task for those who have ceased to be.” Guyotat’s childhood stutter returns, he is frequently kicked out of homes, misunderstood by former friends, grown accustomed to sleeping out in the cold of empty landscapes: “...nothing wounds me more in the brief recurrences of my emotional self than the incapacity of others, sometimes those closest to me, to see, to understand the effort that I extend to live, to renew with life [...] It hurts that people closest to me look at me with the same eyes as yesterday...the very idea of infinitude is affected.”

Coma, as lexical unit, as physical state, as astral object, as botanical corona--connotes a metamorphic, dynamic, protean inwardness which is at once an écrit and an erasure of Guyotat’s writing processes, none of which ever stay single-tracked or self-contained--because they are connected directly to the imbricated, cross-weaving veins and arteries of a stridently impersonal non-lifestyle. Guyotat does not “style” his life or “life as such” (an unknowable quantity) in his writing practice, nor does he invite the reflexivity of authorial stylization; instead, he secretes and excretes its pulp and remnants, sucks them, consumes them (through his eyes, because he is indifferent to eating for nourishment), spits or shits them out (through his orifices, because he is so often on the threshold of things, in passageways)--a constant “progeniture” that defies the formalist stagnation of genre or the false arborescence of genealogical narratives. Guyotat’s “memoir” is material in the fullest sense of the word: it is intimately connected with the physical and cognitive sufferings that have etched their lyric patterns on the corpus of his life/work, yet evasive of the belletristic static that too often attempts a chronologic and statuesque “summing up” of experience, memory, and emotions.

But Coma (both the book-memoir and the condition) re-enacts a return to origin, a pilgrimage toward the embryonic source of fluxioned thought, of bodies that replace and/or mirror one’s own, of language-space, sex and masturbation rituals, venerated, obliterated corporeality. It is in this sense that coma simulates decomposition, containing within its seedlike status the possibility of a subzero sentience at the margins of, in between, physical life and metaphysical extinction, which at once wraps itself like a halo around the heads of comets, in clusters of trees and saffron plums, in the “life, work, fame, or legend” that fogs and eventually calcifies around the core of a rigorously anti-aestheticized life dispersed among other faces, limbs, and names. In other words, a negative capability (a “ghostly nature”) that generates language through a harangued silence, marking the intolerable presence of the body through a suspension of muscular-facial response, furnishing a socialized, complexly held-up desire for life through a technics of breathing apparatuses, nutritional fluids, IV drips, catheters, intubations, the communal and bodily dependency on others; to be in doubt of Self yet maintaining and preserving the self through other Selves realer than one’s own (terminally suspended) sense-of-self.

Guyotat, embryonic-plasmic figure of his own book, generates countless other selves, other spectral time-unbound I’s: he sees himself in 1947 watching a film short that “narrates the treatment and recovery of a man who is suffering from amnesia,” presaging his own return in future-tense from coma, in similar circumstances. (He would have a memory of childhood, in Summer, to recover him, the child-like Dionysian joie de vivre that disguises itself as sparagmos: “...the ‘joy’ of living, of experiencing, of already foreseeing, dismembers it, this entire body explodes, neurons rush toward what attracts them, zones of sensation break off almost in lumps that come to rest at the four corners of the landscape, at the four corners of Creation.”) Likewise, he is never himself but others: his friends, his family members, his lovers; Samora Machel (prostitute-hero of a yet unpublished epic work); his aunt dying in Broussais Hospital (where he himself would be interned during his coma); or a “man selling manuscript poems” on the street, whom he passes, and of whom he remarks “‘That’s me, really...that should be me.’”

“That man, about my age, coat worn to threads, hands shaking over his metered poetry, is myself if I was not myself. He is what the work I create and its social consequences hinder me from being. The work I create is undoubtedly within me and in my hands like a kind of intercession between me and the world or God... [A]ll that surrounds, ennobles, constructs the little I feel myself to be--that nucleus, that quasi-embryonic origin (thought’s first concern is origin), that embryo--is of a ghostly nature. My truth is in that origin and not in what, of life, work, fame, or legend, has formed around it; perhaps it is in something prior to my birth, in my nonexistence (what is unborn rather than acquired).”There is no temporal fixity, no linear narrative, no chronology to Coma, to being in a coma. It is Guyotat shifting from one temporal plane, one psychosomatic zone, onto another (from dream to the hard-tiled floor and back into memory), with only “the cold space in which to pass from one being to another.” In one section it is 1959, and he is fleeing to Paris as a nineteen year old, a 9.5 mm second-hand movie camera in hand, shooting “statues, plants, animals, insects, birds.” Only two pages later it is 1977, Guyotat is in Ville-d’Avray--on a terrace listening to the collective, hypnotic chant of bullfinches. He poetically disassembles the lyricism of the French word bouvreuil, lusts for its sonic/semantic freedom, sucks out of its phonemic shell a primordial juice, a sustenance: “Physical laws keep us apart. The ease of birds, the torment when depression removes you from the world: non-depression is winged feet, whatever the obstacles.” This form of interstitial writing (advanced by repeated use of dashes, semi-colons, elisions, ellipses) fractures the text (as memory is fractured) and dissects the compacted ligaments, joints, appendages, and flesh correspondent to the organ-machine of the body, creating an actual physical distance in textual space: “His leg--where is it now? thrown away? burned? chopped, mixed into dog food?--itches.”

Accordingly, as Hermes, as bullfinch, as comatose wanderer, as textual anatomist, Guyotat’s praxis is migratory, fleet, nomadic. Yet it is the “physical,” and the laws that mobilize the weights, measures, and forces of a disturbingly atomistic world (a world of sudden integration, as well as spontaneous disintegration), which stages the circumference of Guyotat’s literary geomancy, his time and place-shifting, and which eludes but interminably attracts the pinpoint of his stylus, driving it “from one being to another” in a mimetic ritualism (action followed by action, heroic act displaced by subterranean gesture, invariably in sequences of violence-sex-defecation) that would be virtuosically mobilized in his novels (Tomb for 500,000 Soldiers [1967] and Eden Eden Eden [1970] his most well-known and notorious). The incessant eros of his literary craft moves him outside (from the falsely interior, the “Self”), into the Open, spilling out onto the fields not of production or productivity, but of kinetic potential, at a site “where the writing spills over onto the image” and breaks from the facile nature of occidental narratives and historicities: “The scene that shall become The Book stretches to the dimensions of History. To flee Western geography. I write outside, pushing on until the onset of winter chills, traveling back through humanity’s past as the weather grows colder. As the sky and earth are transformed above my head and below my feet.” The desire to flee the spacetime of the page, of historical concretion, of the scriptum itself, drives Guyotat past the initial surface of socio-political stagnations, past even the hegemonic notion of “The Book” (signaling not only the act of composing a babelian version of the mythic counter-book, Le Livre [published 1984], but the Mallarmean Livre itself, the Book of Life that ingests and takes on the shape of an unstable, infinitely-progenitive Lucretian universe, with its own cosmos, its sun and stars and supreme accidents, but also its Ground, its earthen planes, its motley fields and harvests, its valleys and undulant hills):

“I work under a Sun that does not move and on a teetering, spinning Earth, I feel it--that is what I want to impart, in the language of what is becoming a book, the feeling of that rotation. I feel it strongly, I often see it in dreams as well: the curvature of the Earth, because of how I am placed, and where, I see the curvature of the Earth, in imaginary places as well, a kind of Hyperborea hailing from above Scandinavia, infinite, blue, scintillating, endless archipelagos, endless planet, endless world; extraterrestrial spaces are enclosed within the space of the Earth itself. In these visions, I see the curvature of the Earth itself. In these visions, I see the curvature of the Earth at the end of a tilled field: the furrows drawn by Bruegel’s sower follow the curvature, not of the hill, but of the Earth.

“When writing, I settle into the central axis of the Earth, my existence, as a humble plowman of language, is grafted onto that axis, onto the axis of that movement, which is more grandiose than human movement alone: the movement of the planet: the rotation of the planet, with its sun and stars: and in this way to elude even the feeling of death.”Guyotat’s pilgrimage toward the shrine of decomposition, dissolution, the destruction of the Self, attains a religious dimension, one in which “infinitude” survives the conversion of the I into a We; the figure of his Catholic mother, a Saint Monica to Guyotat’s Augustine, recurs throughout Coma, along with “[her] God...the assistance of He who wanted what I am, and of she who carried me to become it.” The hope to “explode that ‘I’ which tortures me” (the principium individuationis that chains Guyotat to the Apollonian spacetime of the page) acquires the qualities of sacrifice (“the closer I get to the end, the more I give to all, as if to lessen, reduce the distance between everybody who will live, and me who will disappear”), one in which a “hypermateriality” arises in the secret life of objects, things, people, animals, the inanimate and sentient alike--“It is that fear, that an object might find itself alone and bereft of purpose...that turns into the obsession of materiality: for the luster of rocks or the dried-out insect or for the pen cap...” A return to materiality at any cost, the conversion of Word into Flesh, of noun into matter, at any rate. That Coma ends with the words “Patience, patience,” (sans period, a comma indicating the possibility of a continuous progression) signals Guyotat’s triumph over not only the comatose state that nearly silenced his voice permanently, but over the subjugations and imprisonments which the historicities which marked his life had predicated upon him; patience understood as gift (a communal self, a deterritorialized self) and as virtue (writing praxis, breathing practice). Coma formulates, at the root level of its constructions and at the lateral velocity of its visions, the lyric testimony/testament of Orpheus, eyes washed out in Lethe, yet with memory miraculously intact, newly returned from the Underworld of the blood-dry and the voiceless.

Jose-Luis Moctezuma is a current doctoral student at the University of Chicago. His studies focus on technologies of the image in poetry, cinema, and literature. His work has been/will be published by Berkeley Poetry Review, PALABRA, and Cerise Press. He is an editor and writer at Hydra Magazine.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig