by Simon Demetriou

Published by Semiotext(e) / Active Agents, 2016 | 384 pages pages

“We shall have everything we want and there’ll be no more dying” – Frank O’Hara

After the attack on the Pulse nightclub in Orlando earlier this summer, I re-read the Frank O’Hara poem “Ode to Joy.” Its refrain: “No more dying,” an idiosyncratic refusal of death and suffering, seems to be what we say every time we gather together, when we dance together and sing together and read poetry together and look at art together.

and the hairs dry out that summon anxious declaration of the organs as they rise like buildings to the needs of temporary neighbors pouring hunger through the heart to feed desire in intravenous ways like the ways of gods with humans in the innocent combination of light and flesh or as the legends ride their heroes through the dark to found great cities where all life is possible to maintain as long as time which wants us to remain for cocktails in a bar and after dinner lets us live with it No more dyingThe Pulse attack was so horrible, among other reasons, because it hit at life in a moment of celebration—as with the attack on the Bastille Day celebration in Nice, or on the Ramadan iftar in Baghdad.

Then I remembered Robert Glück’s story “Sanchez and Day,” from his book Elements of a Coffee Service (1983). It’s an autobiographical story about a homophobic threat of violence. The story ends when the protagonist escapes the men chasing him: “I stood a minute, enjoying the sheer pleasure of breathing in and out. I resolved to make my bed, throw away papers, read Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, have an active, no, a famous social life.”

I love this passage for its ebullient claim that life lived fully is a resistance to violence and death. Not just survival: but sheer pleasure. Not just active: famous.

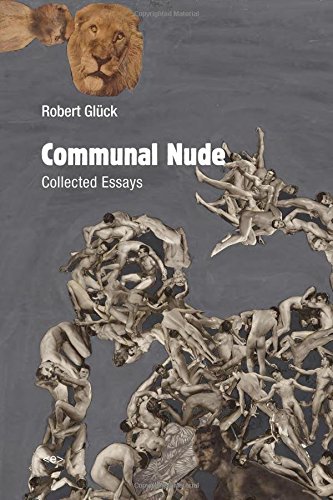

Robert Glück’s writing profusely avows this enthusiastic embrace. In his new collected essays, Communal Nude, we witness his abundant engagement with life as a queer resistance to death and suffering. Glück writes, in his 2010 essay called “Queer Voice”: “When I look at the sky, it becomes a homosexual sky. When I sit in a chair, it becomes a queer chair. I exhale queer atoms. Words are homosexual when I use them, or do I attract queer words?” Sexuality for Glück is a way of being in the world, informing and defining how we relate to others, to loss, to the non-human world, and to writing itself.

For Glück, queerness is a mode of relation that does not hierarchize but instead sees the world as endlessly reenchanted and reenchanting. As Glück writes about the artist Frank Moore: “When I reject the opposition between myself and the rest of nature, wonder replaces terror. I redefine my health as an enormous complex web, an ecology. I enter an enchanted realm whose magic is simply that I coexist with other organisms.” Or as Glück writes about using Vaseline and Crisco as lube: “They turn skin into silk, a medium that wants to shine, to be touched, a surface deep and reflective. One feels depth in the skin, the skin unfolding unendingly like the Virgin’s mantle, and the nerve endings drone with pleasure.” The objects that draw Glück’s attention are avenues for these pleasures that are at once shattering and wholly relational. And the miracle of queer writing is that every part of the world becomes this kind of avenue.

Communal Nude covers a wide range of materials and interests: Glück examines gardening and the burial of his beloved dog; writes a hilarious letter to Kevin Costner, encouraging him to embrace the queerness of his animality in Waterworld; recounts gossip surrounding Ron Goldman and the OJ Simpson trial; shares a diary of his brief imprisonment following an anti-nuclear protest in 1983. When I first got my copy of the book, I would flip through at random, wondering where Bob would take me next.

But the true focus of the book – filled with essays and appreciations for Kathy Acker, Robert Duncan, Gail Scott, Edmund White, Kathleen Fraser, Jess, and others – is on queer writing and art.

Most of all, and most importantly, Glück clearly and powerfully outlines the claims and the importance of New Narrative writing, a movement which he and Bruce Boone founded in the late 1970s. “New Narrative” describes a group of writers centered around Glück and Boone (to whom Communal Nude is dedicated), which emerged in the context of innovative feminist poetics and the high theory of Language poetry. The group primarily revolved around workshops Glück ran at Small Press Traffic in San Francisco in the late 1970s and early 1980s; writers involved included Dodie Bellamy, Kevin Killian, Camille Roy, Steve Abbott, Sam D’Allesandro, and Mike Amnasan. Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, and Gail Scott were other important figures outside the immediate circle. Like the Language poets, New Narrative deploys experimental literary techniques and forms towards radical political and communal social ends. Glück makes the connection explicit:

To talk about New Narrative, I also have to talk about Language Poetry, which was in its heroic period in the seventies....Language Poetry's Puritan rigor, delight in technical vocabularies, and professionalism were new to a generation of Bay Area poets whose influences included the Beats, Robert Duncan and Jack Spicer, the New York School (Bolinas was its western outpost), surrealism and psychedelic surrealism…If I could have become a Language poet I would have; I craved the formalist fireworks, a purity that invented its own tenets. On the snowy mountain-top of progressive formalism, from the highest high road of modernist achievement, there was plenty of contempt heaped on less rigorous endeavor. I had come to a dead end in the mid-seventies like the poetry scene itself. The problem was not theoretical—or it was: I could not go on until I figured out some way to understand where I was. I also craved the community the Language Poets made for themselves.Glück participated in the 1981 Left/Write conference organized by Steve Abbott and Bruce Boone; and Boone's 1980 novel Century of Clouds relates his attempt to convince Marxist theorists like Fredric Jameson, Stanley Aronowitz, and Terry Eagleton (at the Marxism and Theory group in St. Cloud, Minnesota) of the importance of sexuality to Marxism.The questions vexing Bruce and me and the kind of rigor we needed were only partly addressed by Language Poetry which, in the most general sense, we saw as an aesthetics built on an examination (by subtraction: of voice, of continuity) of the ways language generates meaning. The same could be said of other experimental work, especially the minimalisms, but Language Poetry was our proximate example.

While the Language writers often avowed a suspicion for the first person (in the form of the lyric subject), Glück and New Narrative privileged narration, caricature, and anecdote. The disagreement, however, is one of expansion: arguing that the communal and political possibilities in writing could emerge from many kinds of disjunction. Glück stakes a claim for the political importance of a community narrating itself while coming into historical consciousness.

I wanted to write with a total continuity and total disjunction since I experienced the world (and myself) as continuous and infinity divided. That was my ambition for writing. Why should a work of literature be organized by one pattern of engagement? Why should a “position” be maintained regarding the size of the gaps between units of meaning? To describe how the world is organized may be the same as organizing the world. I wanted the pleasures and politics of the fragment and the pleasures and politics of story, gossip, fable and case history; the randomness of chance and a sense of inevitability; sincerity while using appropriation and pastiche. When Barrett Watten said about Jack the Modernist, “You have your cake and eat it too,” I took it as a great compliment, as if my intention spoke through the book.For participants in political movements, Glück argues, there is something more than the correct and objective political analysis required. It is also important to understand how it feels to be in that movement, how lives are changed and affected by politics from the inside. That narration would include gossip, anecdote, fable, real names.

The essays in Communal Nude show abundantly that the work of critique can align with play. If this is having one’s cake and eating it too, perhaps that double positionality has its virtues. Glück and other New Narrative writers were interested in the oscillation between text and meta-text, between the story and the telling of the story, as a way to think critically while retaining the first person perspective. This is not, however, an ironic move in which the story itself is somehow devalued by its ever-present analysis, but a pleasurable play between perspectives that does not hierarchize. Glück writes of his reading of Proust: “What I took, and in that sense what I became, was the murmuring, the whisper that is a meditation that unfolds on itself, making itself up as it goes—that I could tell a story and also be the one to endlessly speculate on its meanings and the nature of storytelling itself.” For Glück, text-metatext has a real political function. “The metatext cuts naturalistic illusion. It includes the reader, it asks questions, asks for critical response, makes claims on the reader, elicits commitments. In any case, text-metatext takes its form from the dialectical cleft between real life and life as it wants to be.” But as Glück consistently attests, every dialectical cleft is also a sexual cut. The turn from text to metatext might be the pleasure of switching. As Glück writes in his novel Jack the Modernist (1985): “Although I like to pitch and catch, I just wanted him in me. Accepting my body and the world took that form.”

The transformation of the world along an itinerary of pleasure reflects Glück’s broader political commitments, his writing’s avowed resistance to our troubled political times. Several essays attend to the AIDS epidemic (most markedly “HIV 1986,” and an excerpt from Glück’s AIDS memoir in progress, About Ed); other essays describe an anti-nuclear protest camp and the relation between writing and nuclear catastrophe. But what Glück’s writing shows us is that even a review of “the best lube” is political. Following Bataille, whose work is the subject of several essays: “a gay bathhouse and a church could fulfill the same function in their respective communities.” Against some forms of religious and political belief, Glück believes that we can have joy and pleasure in our lifetimes; his writing attends to the forms of community that make those possible, staunchly and communally (and nudely) refusing the life-denying forces of war and violence and hatred.

Bob shares pleasures in his prose and we feel them too, delighting in his sentences. He is a master constructor of the prose equivalent of an earworm, the sentence or simile or idea that gets in your head. Here is one moment that I could not forget from Communal Nude: “I would like nothing better than to have sex with God’s angels. The desire to have sex with God’s angels seems natural to me—in fact, more natural than desires less supernatural. The angels were equipped for the occasion with human flesh and they wanted to take that brand-new meat and drive it around the block. There’s no question who would be on top: the glory of hospitality belongs to the one who entreats the guest to enter. Now that I’m really imagining it, I am going to take a twenty-minute break from this essay, goodbye.” Now I am thinking about this too, and I am telling my friends about it, and talking about being fucked by angels all the time, especially when under the influence of substances that bring us closer to the divine. But it’s an apt metaphor for Glück’s writing, because his prose is one of those substances: it feels snatched from the heavens and evidence of the heavenly in our lives, to which we should only be perceptive, initiates in “Bob’s fundamentalist movement.” (There’s a pun on “fundament” that you will have to read the book to discover.)Put quoted sex next to quoted anger next to quoted tenderness—is it a story or a list of items equal to each other? Where in the infinity of equal signs is the referent, the guest who doesn’t come? We plump the pillows and wait disconsolate by the phone. But think of all the divine strangers who did bring us their elated appetite—Mary and Joseph, angels, prophets, gods. I like this mix of domesticity and the sublime. Food and shelter, food and shelter, humiliating as a plotline—exactly what we don’t want to need...Did we believe in the “truth and freedom” of sex? Certainly we were attracted to scandal and shame, where there is so much information. I wanted to write close to the body—the place language goes reluctantly. We used porn, where information saturates narrative, to expose and manipulate genre’s formulas and dramatis personae, to arrive at ecstasy and loss of narration as the self sheds its social identities. We wanted to speak about subject/master and object/slave.

While I wholeheartedly recommend this book, and hope that its large circulation will bring more readers to Glück’s writing, I might make a stronger plea that you also go find one of Glück’s works of fiction, particularly his short story collections Elements of a Coffee Service (1983, and republished as Elements in 2013) and Denny Smith (2004), and his novels Jack the Modernist (1985) and Margery Kempe (1994). Perhaps my favorite piece of Glück’s writing is an excerpt from About Ed, his novel in progress and AIDS memoir about Ed Aulerich-Sugai, an artist who was Glück’s lover in the 70s. This excerpt, which appears in a “Belladonna Elders Series” volume shared with Sarah Schulman, circles around a haunting phrase from a Frank O’Hara poem: “Is the earth as full, as life was full, of them?” Glück writes: “Life can only understand itself, but that is not the whole story. Since I could not mourn Ed, I could not recognize his death. I could not acknowledge his presence in my life as a dead person. That is, I could not bury him, so I was ‘maintained’ outside of life. As death is full. I needed to pull over a moment. As death is full, as though in the full sunlight. Some rain splashed on my face—I felt it. It made me want to lift my face and make a vase with my arms. In my mind I lifted my arms into the shape of a vase, another word in the language of Ed’s death.” In this miserable summer of death, I’ve been rereading this story. Not as a consolation for the fucked up world we live in, but to make the shape of a vase in my mind, a space for mourning. Glück’s writing offers this capacity, this space for thinking and being and feeling, both with joy and with suffering.

Less in the journalistic interest of “full disclosure” and more in the New Narrative interest in gossip and anecdote, let me tell you about my tea with Bob. Last year I asked my friend Jocelyn Saidenberg, who has been friends with Bob for many years, to introduce me, and she set up a date. Bob had us over to his house in Noe Valley for tea. “Are you the one who’s writing a dissertation comparing Bob and Bruce to Dorothy and William Wordsworth?” his son asked laughing. (I am—a chapter, at least.) Bob said, “Do I get to be Dorothy? Why does Bruce get to be Dorothy?” (Spoiler alert: They both get to be Dorothy; even William gets to be Dorothy.) As I was about to leave and sheepishly asked Bob to sign the array of his books I had with me, he said I shouldn’t be embarrassed. “I never got any of my books signed,” he said, gesturing to his vast library surrounding us, “and now so many of my friends are dead.”

If I come across as more of a fan and less of a critic or academic in this review—good! That’s not to say that Glück’s writing does not merit scholarly attention—it does. Ultimately, however, in its intense and loving appreciation for the things of this world, it encourages a more intimate devotion. In our finitude, our exposure to death and suffering and loss, it is more urgent to love Robert Glück’s writing than to subject it to rigorous scrutiny and criticism. Glück’s writing, a paean to the political and social functions of pleasure and delight, will show you how.

Daniel Benjamin is a PhD student, poet, and part-time caretaker living in Berkeley, CA. With Claire Marie Stancek, he is the co-editor of Active Aesthetics: Contemporary Australian Poetry (Tuumba Press / Giramondo, 2016). He is also the author of the afterword for Jack Spicer’s The Wasps (speCt!, forthcoming 2016). Other projects include a dissertation entitled On Lyric’s Universals: How Poetry Says “We,” 1955-2015; and a poetry manuscript.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig