by Simon Demetriou

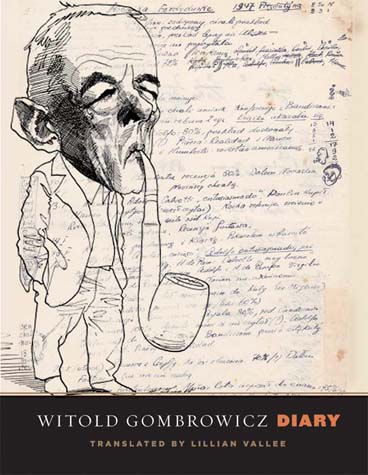

Published by Yale University Press, 2012 | 800 pages

The twentieth century has given us a lineage of European authors, chased – away from home, from nation and native language – by the monstrous History of the recent past, driven into the status of refugee. One subgroup of these modern exiles, fated to a life of perpetual clandestine travel, materialized in the writings of Emilio Prados (1899-1962), Elias Cannetti (1905-1994), and Witold Gombrowicz (1904-1969). Walter Benjamin provided for this group a philosophical argument for a path towards a sense of rootedness, precisely in exile, in his classic essay “On the concept of History” (1940), a critique of historic materialism and assertion of History as present. Hannah Arendt, in her 1946 article “We Refugees,” brought this argument to bear specifically on the person of the twentieth century political exile, on whose back, she argued, the West could rebuild after the atrocities of fascism. The literary lineage which Gombrowicz helped found positions these ideas of Exile, Rootedness, Tradition and History at the center of its thought.

Gombrowicz developed his own peculiar take on History and Tradition, one of grief, wittiness, humor, bitter wisdom and a hilarious irreverence that leaves nothing—not even its own author—unscathed. The accident of his being in Argentina in 1939 on the day Germany invaded Poland meant that he too suddenly joined the ranks of the refugee, a particularly difficult status considering he spoke no Spanish, was without money or prospect for work, and suspected—as any artist would—that he would lack a proper audience for his work. Unbowed, he obtained a job in a bank thanks to a compatriot who admired his literary work, dedicated his office hours to penning the novel Trans-Atlantic, translated some of his previous works into Spanish and pursued friendships with Latin American intellectuals. This is the environment in which he entered into a deep dialogue with his circumstance, a dialogue that would become his Diary, composed in the shadow of The Journals of André Gide and the Essays of Michel de Montaigne.

Expertly translated by Lillian Vallee—who also penned the emotive and beautiful translator’s afterword—and including the brief but insightful foreword by Rita, this 2012 complete edition of Diary is notable for the addition of twelve previously unpublished entries that were missing from the 1986 Polish edition, upon which other previous editions had been based. That influential Kraków edition, crucially, had been censored due to alleged criticisms of the USSR regime. The gesture was of course ultimately futile. His censors could not erase the devastating gaze of this unorthodox thinker evident in Gombrowicz’s every thought: Witold’s demystifying wisdom is contagious to such degree that the thoughtless revision and censorship of the text could not prevent the reader from destroying fake idols. This Vallee edition also includes three important inclusions in its afterword: a chronology of the author’s life, an index of other Gombrowicz’s works mentioned through the Diary, and an indispensable and erudite subject index. Indeed, due to the text’s length, the subject index takes on added importance; as with Joyce’s Ulysses, Diary is an immensely allusive text, one that will require scholarly attention for decades or more to come. Again, however, as with Joyce, one suspects that Gombrowicz would appreciate a flaneur reader as much as a scholarly one, dabbling here and there—after all, snobbishness and faux seriousness are among the most recurrent targets of Gombrowicz, the iconoclast.

One element is missing from this edition and I must confess it puzzles me to weigh the reasons of its absence. Neither in Rita Gombrowicz’s foreword nor in Lillian Vallee’s afterword is there an emphasis on Witold’s Argentinean soul. It is true that his many years in South America were circumstantial, and also that he kept writing in Polish – this is without question the work of someone who never ceased thinking of himself as Polish, or even, perhaps moreso, European. But life is persistent in its desire to subvert our expectations and intentions, as Gombrowicz himself acknowledges upon his eventual return to the old continent: “I had been unable to muster anything more personal and original when confronted with Europe after a twenty-five-year absence, I, a newcomer, an Argentinean...” And, a few lines earlier: “Poland. Argentina. The two mythic tigers of my history, two waves washing over me and ravaging me with a terrifying nonbeing—because this no longer is, it was.” Gombrowicz’s Diary reveals him to be acutely conscious that he, partially determined by who he had been and believed he would be again, was just as much determined by who he had come to be: an exile, always in transit, in between, yet all the while, even after his return to Europe, motionless, a resident, an Argentinian. There is a previous version of the text “Against the Poets”, for example, written originally in Spanish—of which the translator makes no mention. The tensions of influence and antagonism that Gombrowicz developed with Latin-American authors are legion throughout Diary, but there is no discussion of them in this edition’s commentary. South America considers Gombrowicz as one of their own—both for what he gave to and what he received from that part of the world—and it’s certain Gombrowicz felt likewise.

As history would have it, Gombrowicz was integral in the development of a modern tradition that centers on the individual, mixes fiction and testimony, and dwells on loneliness, belonging, identity, art, and, of course, History and its heavy burden. It would be difficult to overestimate the relevance of the Diary on subsequent Western high culture— on the writings of our immigrant authors, our travellers, Milan Kundera (b 1929), Sergio Pitol (b. 1933), Claudio Magris (b 1939), W. G. Sebald (1944-2001), Adam Zagajewski (b 1945), Salman Rushdie (b 1947), Enrique Vila-Matas (b. 1948), and Teju Cole (b 1975), etc.)—though it is also impossible to forget or deny that Diary was written from the margins of what it itself was ultimately to – at least symbolically, influentially – conquer.

Aguillón-Mata was born in Mexico City in 1980, studied Hispanic literature in Mexico, Germany and the US, and published a book of fiction in 2004 titled Quién escribe (Paisajista) . He is a past and future contributor of fiction and translation to MAKE, and his next two books, Envés and Tratado (De Una Zona Privada), will be available this fall.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig