by Surya Bowyer

Published by Steidl, 2012 | 180 pages

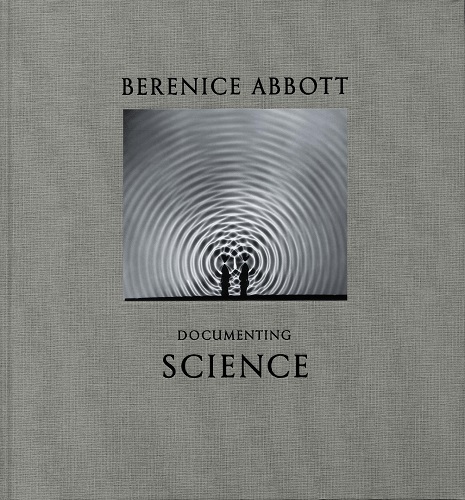

Looking through Documenting Science, the recent monograph of Berenice Abbott’s “science” photos, one can’t help but hear the echo of Walter Benjamin’s oft-repeated “optical unconscious.” “It is another nature,” he writes, “that speaks to the camera than to the eye.” “Details of structure,” “cellular tissue,” the “physiognomic aspects” of “the smallest things”—these previously imperceptible “image worlds” open up, blurring the line between “technology and magic.” Through photography, entire subterranean layers of nature—“meaningful yet covert enough to find a hiding place in waking dreams”—emerge into human vision.

While the “optical unconscious” is a phrase that lends itself to multiple inflections (the psychoanalytic, the political, the poetic), it is indeed “another nature” that Abbott’s photography reveals. It is not a version of nature, however, that Benjamin, writing in the early 1930s, could have glimpsed in the existing photographic archive of botanical specimens and microscopic samples. Taken primarily during the years of accelerated research that led up to the Space Race, the impressively abstract images of light and gravity, cycloids and electromagnetic fields collected in Documenting Science make evident an obsession with a newly, and intensively, technologized nature.

It was under the official aegis of this nationwide investment in mapping and conquering the laws of physics, mathematics, engineering, etc. that Abbott—a photographer already well known for her classic cityscapes and portraits—began her exploration of science as a photographic subject. From 1958 to 1960 she worked under commission for the MIT-based Physical Science Study Committee, a post-Sputnik initiative for classroom reform. Illustrating a range of scientific principles, her photos from this period would appear for the next several decades in mass-printed textbooks and laboratory guides. Republished here in a large-format art book, their virtuosic clarity as pedagogical examples also points to the experimental core of Abbott’s practice.

In many ways the open-ended possibility for technical, aesthetic, and social experiment was what drew Abbott to photography in the first place. Born in 1898 in Springfield, Ohio, Abbott drifted in and out of school as an aspiring sculptor, then journalist, then poet, before moving to Paris in the 1920s. Hired as Man Ray’s darkroom assistant (for her lack of experience and thus easy trainability), she went on to establish her own portrait studio, photographing the literary and artistic beau monde of the era. Following a formative encounter with the work of Eugène Atget, she returned to the States in the 1930s where she spent the next two decades charting out a comprehensive record of urban New York. With her belief in the photograph as a document of the unseen, Abbott strived “to reach the roots, to get under the very skin of reality.” “The form of the photographic picture,” she demanded, “must grow out of a clear understanding of the meaning of the things photographed.”

Abbott’s scrupulous working methods toward this end are vividly evoked in the production notes included throughout Documenting Science. Hers was neither the fly-on-the-wall, instant-click street photography of her contemporaries nor the misty sentimentalism of the Pictorialist tradition she abhorred. She was supremely interested in the composition of an image—in making the photograph striking or beautiful—but only as a function of its precision. The consummate balancing act of Abbott’s approach is captured in her comments, for instance, on Transformation of Energy, which traces the fluid arc of a pendulum swing to demonstrate potential and kinetic energy:

I planned this photograph very carefully to make it balanced; what is more balanced than science? The photograph had to balance. It had to be subtle, not just an arty composition. It was difficult to construct the apparatus; then we had to paint it correctly. It was important that part of it be gray, not white. The photograph was a tremendous challenge, but here I missed a little. This one should have gone on 1/30 of a second longer.Such a back and forth between the logistics of the photograph and that of the material world defines the appeal of Documenting Science. Abbott’s technical exactitude illuminated a field in which, as she put it, “there was usually no precedent to go by.” Her necessary invention with each photograph is literalized in Parabolic Mirror, a surreally disarming depiction of a woman’s single, open eye, refracted and mounted on a makeshift ferris wheel in an ocular frieze of simultaneous surprise and horror. This photograph, Abbott notes, was one of the most difficult she ever had to orchestrate, requiring a team of assisting scientists to fashion a series of “homely devices” that could accurately catch the right angle of the dozens of small mirrors reflecting the eye. The meticulous attention and labor behind this and other photographs revives them as miniature set dramas. “Nature” is staged to the measure of Abbott’s lens, manifesting a vision as sophisticated as it is austere.

Arguably, though, the most stunning images in the book are not quite photographs at all, but photograms made without a camera or a lens. Where Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy directly placed objects on sensitized paper to generate their photograms, Abbott innovated a strobe light and pinhole system that could fix the movement of water as she rocked the developing tray of a specially built “ripple tank.” Her efforts resulted in a liquid typology of “Rayograms in motion”: Expanding Circular Waves, Time Exposure of Standing Waves, Interference Patterns, and so on. The actual sleight of hand behind these images not only muddles the distinction between “technology and magic,” it gestures toward what Jeff Wall has elsewhere described as the “immersion in the incalculable” that is nature itself. Abbott’s remarkably photogenic waves coax out this incalculability; the endless variability of their curved and lit striations glimmer and practically reverberate on the page.

Other ur-forms of twentieth-century “nature” appear in Documenting Science: the cylinders, spirals, globes, and tendrils of computer wiring, radio tubes, and electrostatic generators. Photography, as in its earliest iterations, is called upon to taxonomize the incalculable order of the natural and, increasingly, technological world. Yet Abbott, like Benjamin, could not have anticipated how quickly the medium would outdate even itself, becoming ever more intertwined with the immateriality of the digital. Nonetheless, as documents of a future in the making—as well as of photography’s vital role in picturing it—Abbott’s science photographs fulfill her own dictum: “It is beautiful because it has fulfilled its use, recording the subject completely and understandingly.”

Jennifer Pranolo is a PhD candidate in Film and Media at the University of California, Berkeley.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig