by by Margaret Kolb

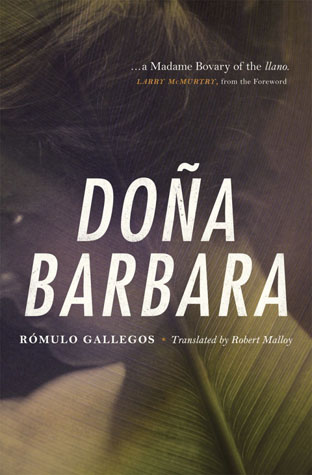

Published by University of Chicago Press, 2012 | 440 pages

“If Señor Gallegos is one-half as good a President as he is a novelist,” reads the original New York Times review of Doña Bárbara, “Venezuela is a lucky land.” From humble origins, Rómulo Gallegos was working as a teacher and a journalist when he published Doña Bárbara. Due to veiled allegorical criticisms in the novel of the then-ruling regime, Gallegos was forced to flee Venezuela for Spain after its publication. He returned to his homeland seven years later, became politically active, and, in 1947, was voted in as Venezuela’s first democratically elected president. Ousted by a coup after nine months in power, Gallegos took refuge in Cuba and Mexico, where he worked on human rights affairs. He returned to his homeland after his second exile in 1958 to international acclaim and a Nobel Prize nomination.

Doña Bárbara, first published in 1929, became an instant cultural touchstone, both in Venezuela and throughout Latin America. A precursor to the magical realism that would soon make the continent’s literature famous, it’s simultaneously also a rural regionalist novel, a Latin American equivalent to Twain, Eudora Welty, etc. Yet Gallegos, of urban Caracas origins, never lived in the llano, the rural grassland plains, himself. In a triumph of observation that must be among the great intellectual feats of world literature, Gallegos spent just eight days researching the llano and its people in preparation for Doña Bárbara, what many now consider the region’s definitive work.

Doña Bárbara reads like a western-cum-fable, a parable with the trappings of a cowboy adventure story. Its characters come to us first as types – the saintly doctor, the temptress – then gain depth and complexity as the story progresses. Dr. Santos Luzardo is Reason and Civilization embodied, descended from a long line of violent patrones, landowners who succumbed to the chaos of the plains. He returns to his family’s farm, Altamira, to make right on the wild countryside and look for “hidden springs of goodness in his people and in his land.” There, he quickly finds a nemesis in Doña Bárbara, a sensual cowgirl enchantress and embodiment of “barbarism” and the wild frontier. Her land is called El Miedo, “Fear,” and she governs it accordingly, with caprice and revenge. Ostensibly an archetypal frontier confrontation, the novel unfolds into something far more nuanced, a vivid representation of a rapidly changing continent, as Latin America’s feudalistic past and technocratic promise struggled for political foothold.

As the book progresses it gradually becomes clear that the center of the book is neither Luzardo nor Doña Bárbara, but instead the unforgiving grassland plains of the llano. I grew up in Iowa, and Gallegos’ description of the llano is remarkably similar to the texture of my own childhood memories: the endless horizon, the violent swings in temperature, the stoic men. But the llano is not the American Midwest; it has its own fickle-willed agency and a mercurial power over the cowboys who roam it. It is tumultuous, alive; it crawls into one’s consciousness and takes root there. As Gallegos writes, “the Plain crazes.” Gallegos alludes to the llano’s crafty power when he describes the downfall of Lorenzo Barquero, Doña Bárbara’s alcoholic ex-lover. He was “a victim of the ogress, which was not so much Doña Bárbara as the implacable land, the wild land, with its brutalizing isolation...”

As noted above, Doña Bárbara is, at least partially, an allegorical critique of the political situation in Venezuela when it was written. Then, Venezuela was ruled by Juan Vicente Gómez, a military general and dictator who oversaw the country as it reaped the benefits of recently discovered oil wealth, installed a high-quality infrastructure, and raced blindly towards modernity. Yet Gómez was also brutal and unforgiving. In Doña Bárbara, Gallegos highlights the ambiguous nature of both progress and tradition, and calls into question whether there is “a single straight way towards the future.” Gómez’s regime quickly discerned that Luzardo, in his obsession with fences and order, in many ways echoed Gómez himself. Thus Gallegos flew into exile.

In many US Latin American literature survey classes, Gallegos has been swapped out to make room for acknowledged masters like Vargas Llosa, García Márquez, Borges and Cortázar. Yet Gallegos, their predecessor, is a clear influence on all Latin American authors who came after him, both in his virtuosic regionalism and his hints of the fantastical that lurk just beneath Doña Bárbara’s surface. Like García Márquez – whose characters have been known to rapture into the afterlife, fall to Earth from heaven, and reign until the ripe old age of 232 – Gallegos strews his novel with uncanny, albeit subtler, details. Houses move furtively in the night, bending borderlines like clocks in a surrealist painting; a sorceress sees visions of her enemy in a glass of water; a lance head stabbed into a wall changes a family’s fortune for generations. Yet nothing ever quite stretches the imagination into outright fantasy. Above all, beneath all, there is the llano: material, textured, tangible. In the vigorous, colorful, unforgiving terrain of the Venezuelan countryside, these strange happenings are not symptoms of magic. Rather, they’re the dreamlike nuances that shade daily life on Gallegos' deftly imagined, brutally real plains.

Erin Becker is an MAT student and Spanish teacher at the University of Iowa and a graduate of the English and Creative Writing program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her interests include media literacy and the relationship between propaganda and art.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig