by Surya Bowyer

Published by Yale University Press, 2011 | 371 pages

“Each individual has an idealized version of the self which they would prefer to offer to the world at large, and with the aid of a mirror, this publicly visible façade can be carefully constructed.” The mirror, once a symbol of the Virgin Mary, now perhaps predominantly a tool – or weapon – of self-portraiture and self-interrogation, “stands," Ribeiro writes, "for good and evil; for sacred and for profane; for the spiritual and the worldly.” As recently as the seventeenth century, the mirror became a household necessity in Europe, taking center stage in the process in the history of cosmetics. Which is where our story begins.

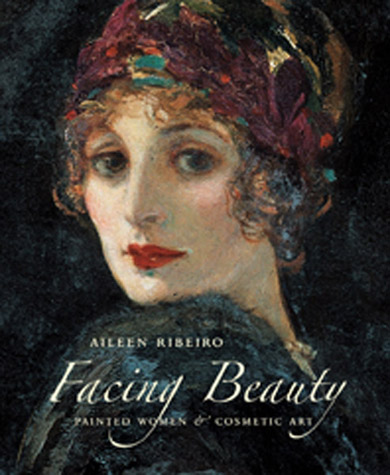

Facing Beauty, a work of meticulous historical and cultural scholarship, examines artworks of the Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Modern periods to investigate the evolution of Western conceptions of female beauty. In so doing, it documents the changing ways it has meant, and continues to mean, to be female. Do we as women, as Nancy Baker suggests, get caught in a “beauty trap” in which we chase “elusive and transient feminine beauty,” instead of searching for “real power, economic freedom and self-reliance”? Or do we use cosmetics to enhance our natural beauty while cultivating our inner beauty?

The earliest evidence of the use of cosmetics dates back to Egypt in 4,000 BC. They began with the use of pumice stones, oils, creams, ointments. To color the face one used “...white lead powder or wheat flour, the cheeks and lips reddened with wine lees, red ochre or vermilion--red mercuric sulphide, and the eyes outlined with kohl (powdered antimony), ivory black (from charred ivory or bone), lampblack (the burnt residue from oil-burning lamps)...” Harmful ingredients such as mercury and white lead were used (Wikipedia uses the word “many” to describe the number of people who died using such harsh ingredients.). In different countries, rules differed as to how and why to wear cosmetics. Some cultures prohibited their use outright. Around 3500 BCE, the Chinese began to use a mixture of egg, gum arabic, gelatin, and beeswax to color their fingernails, to distinguish between social classes. Facial make-up was used there to celebrate the lunar month. In Europe, as in China, make-up was also a statement of social class: the higher the social class, the more pale women kept their skin. Lead paint was used to keep the skin white, which contributed to poisoning and occasionally even death. Elsewhere kohl was used in places as eye-liner, to ward off evil spirits. Today cosmetics are used primarily to tan the skin. Cosmetics have been used to cover the effects of illness and to counteract the aging process. Men have also worn cosmetics to varying degrees, which brings up questions as to traditional gender roles.

The introductory section of Facing Beauty begins with a discussion of the word “beauty,” providing the reader with a basic backgrounding on the relation between art and cosmetics. Accordingly, Ribeiro highlights the debate as to whether beauty is universal or specific. Francette Pacteau has written that “...what is considered beautiful in a woman varies between historical periods and between cultures,” whereas Arthur Marwick believes that “beauty is universal.” Ribeiro - who explicitly admits that her approach is a Eurocentric one - sides mostly with Marwick.

The first large section of Facing Beauty focuses on the Renaissance. This was the time of the rebirth of classical learning, as “humanist” scholars raced to devour Greek and Roman texts in their original, in the wake of Petrarch’s discovery of a previously neglected, and august, pre-Christian age. With this discovery came a renewed interest in classical art, with its freestanding sculptures (an unpracticed artform for the millennium prior to Donatello) and careful modeling of the human and natural worlds. Accordingly, and importantly for the interests of this book, there followed a growing patronage for art. This ranged from private individuals to churches and high-end official patronage. This was the time of Donatello, Verrocchio, and Ghiberti among others. The use of the linear and mathematical perspectives in work gave a sense of depth, as facial expression and stance (think the off-balance, contrapossto - weight on one foot – posture of Michaelangelo’s David), gave works the impression of life. Artworks once again became tangible, real.

In describing the Renaissance paintings of Parmigianino, Vecchio, and Bellini, Ribeiro notes how women in these paintings are, of course, dressed in exaggerated draperies, often including jewelry. But, Ribeiro suggests, the most notable details of these artworks lie not in the garments of these women, but in their faces. If we take La Bella by Palma Vecchio (circa 1520), one can see the extremely pale white skin and dark red lips. The title itself suggests the desired beauty of the woman portrayed. Ribeiro describes this work as “...being a compromise between the ideal beauty and that of a real woman, verging more towards the latter in specificity of dress and ornament. It suggests desire but desire not necessarily limited to a sanctified relationship...” John Berger has previously made a similar point in his Ways of Seeing: the distinction between institutional “high” nudes and pornography is not always, or perhaps even rarely, as absolute as basic art history would have us believe.

There have, of course, always been people who believe cosmetics to be unnecessary, or, worse, nefarious. Ribeiro notes, for example, that early Christians “denounced [the use of cosmetics] as sinful in itself, against both nature and the explicit wishes of God.” Clement of Alexandria (a pagan philosopher) referred to women “as apes painted white who ‘smeare their faces with the ensnaring devices of wily cunning.’” Interestingly enough, the misogyny of Clement’s statement aside, similar criticisms as to the dubious worth of cosmetics have been shared by various recent and contemporary feminists and critical theorists.

Jumping into the Enlightenment section of Facing Beauty, we are told of a new feminine elite known as the élégantes. These women took their ideas – of Neo-classical fashion; of class and gender roles – to the most extreme, even radical, fashion. Josephine Beauharnais, the first wife of Napoléon Bonaparte, led this group. Another élégante was Juliette Récamier, who was described by Balzac as one of those “perfect, dazzling beauties, whom Nature fashions with peculiar care, bestowing on them her most precious gifts, distinction, dignity, grace, refinement, elegance; an incomparable complexion, its colour compounded in the mysterious workshops of chance.” Joseph Chinard sculpted a terracotta bust of Récamier (1801) which portrayed her “childlike beauty.” Her hair is tied back which allows us to see the round and childlike shape of her face. It is here that it is evident that “the greater the beauty of a woman, the less occasion she has for ornament.” With just a shawl and hair bandeau, simplicity shines through in this work.

Only recently, with the advent of critical theory, have thinkers begun to systematically analyze the influence of societal and economic forces on the use and nature of cosmetics. Sociologist and social philosopher Georg Simmel said in his 1908 work Exkurs über den Schmuk that “...all these practices undoubtedly also have a psychological motive...the final result portrays a desired identity, a phantasmal self-image, an imaginary striving for sexual recognition and social status.” The presence or absence of a cultivated appearance evidences a certain social manner, functions to permit one to be “socially appraised” into the desired class. If you want the role, play the part. In this lineage, Facing Beauty critically analyses how the use of cosmetics, as portrayed in the majority of the artworks described and included in Ribeiro’s book, seems mandated by the demands of ideals of beauty. Ribeiro writes: “The face is a canvas on which to paint the fashionable being but it also depicts the social being, for it is a kind of adornment which may indicate rank and status.”

Ribeiro’s work here is thoroughly researched and informative. Facing Beauty, at 256 pages, is replete with 100 colour images + 50 black-&-white illustrations. It does not read as a textbook, but rather as a well-organized popular work full of gorgeous prints, history, and incisive and often humorous commentary. Ribeiro challenges established ideas about beauty, aging, and the use of cosmetics, and their role in the portrayal of women in Western art throughout the ages.

Stephanie Barner has a Bachelor of Arts degree in Music from the Crane School of Music, and a Master of Arts degree from Brandeis University where her specialty was Musicology. Her current research is in the field of music and medicine. She teaches general music in New York State.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig