by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Yale University Press, 2016 | 368 pages

Death is the end of lots of things, not least speech. Walter Ralegh complained of “cruel time” that “in the dark and silent grave / When we have wandered all our ways” it “Shuts up the story of our days.” This is decease as the end of narrative, or, at least, of narrative control: if, as the cliché goes, dead men tell no tales, the still-living never shirk from making ventriloquists’ puppets of them. Consider, for instance, vanitas, a genre of still-life painting developed by artists of the Dutch Golden Age. In vanitas, a wide array of symbols – including skulls and other human remains – teach viewers about the fleetingness of human existence, and about the virtues they had therefore better cultivate. Memento mori – Latin for “remember that you must die” – is one of the more resilient motifs in all of art, and vanitas, as in this 1603 example by Jacques de Gheyn II, one of its most resounding statements. When William Shakespeare, who was De Gheyn’s contemporary, wrote Hamlet’s plaintive address to poor Yorick’s skull, he installed memento mori at the top rank of the English theatrical canon. In the following century, this sort of thing inspired a proto-Gothic style in poetry that critics have come to call “Graveyard School.” Thomas Parnell’s “A Night-Piece on Death” (1721) describes “Shades” rising from their graves to address the living: “all with sober Accent cry, / Think, Mortal, what it is to dye.” When we compel them to speak – and we do so all the time – the dead and their representatives tend to be eloquent, if hackneyed, moralizers, communicating maxims of unassailable good sense from so many posthumous pulpits.

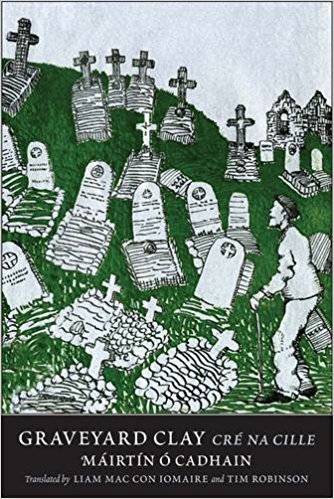

Máirtín Ó Cadhain’s Cré na Cille was published in Irish Gaelic in 1949. It’s a “novel” composed almost exclusively of talk – of dialogue, and much aimless chattering – among dead bodies, languishing in a nondescript bone-yard in the west of Ireland. Readers may be forgiven for anticipating some kernels of existential insight – in a cemetery, claimed Thomas Parnell, “Wisdom’s surely taught.” But had Parnell looked to Ó Cadhain’s corpses for edification, he’d have been bitterly disappointed. In Cré na Cille, the dead speak – garrulously so – but they’re not a bit wise. Their prospects have, instead, been literally curtailed: consumed by the same prejudices and anxieties that preoccupied them in life, their lot has changed only insofar as they are now immobile, which makes it harder to keep up with the Joneses. They remain obsessed by what happened – and what happens – above-ground, but can’t muster more than paranoid speculation. Walter Ralegh’s vision seems desirable by comparison: better perhaps to shut up the story than to let it blather endlessly on. Liam Mac Con Iomaire and Tim Robinson’s raucously successful new translation, titled Graveyard Clay, conveys the spirituous brio of Ó Cadhain’s original for a new crop of English-language readers.

If Graveyard Clay has a protagonist, she is Caitríona Pháidín, whose remains have, at the outset, been newly interred in “the Fifteen-Shilling Plot” – the middle-class portion, so to speak, of the necropole. (Less auspicious, this, than “the Pound Plot,” but not so humiliating as the “Half-Guinea” one.) Early on, she wonders to Muraed Phroinsias, a neighbor-cadaver, whether one loses “all memory of life” in the grave. Not a bit. The cruel and extended joke at the novel’s center is that neither Caitríona nor her plot-mates will forget a morsel of that memory: they are, on the contrary, cursed by it. Ó Cadhain’s reader isn’t exactly prompted to empathize: Caitríona is choleric, petty, and, grudging. She is preoccupied, above all, with wondering whether and when her allotment will be distinguished from the others by a cross of precious Aran Island limestone. She devotes her spare time to inveighing against her undeceased sister Nell, who is accused of undermining Caitríona’s earthly (and subterranean) affairs, especially as regards an inheritance from a third sister, Baba, long since emigrated to America.

These are just the sorts of worries the dead are supposed not to bother about, but Ó Cadhain makes them the stuff of his book. Caitríona’s outbursts frame the general din, but Graveyard Clay isn’t fundamentally her story. It isn’t really anyone’s story, at least not in the conventional sense. It’s more like a cacophony, a bellowing Babel, death as harrowing – and occasionally hilarious – hubbub. “Peace is what you want,” Caitríona admonishes one new arrival. “Isn’t that that what we all want? But you’ve come to the wrong place looking for peace, Bríd…” That ellipsis would make a fit emblem for the text entire, which is less a yarn than an artful jumble of trailings-off, fragments, and redundancies. To read Graveyard Clay is to be bewildered by a deranged chorus of moldering mouths, sometimes addressing one another, sometimes prattling to no one at all. These corpses aren’t transitioning from life on earth to existence elsewhere. They are stagnating, and Ó Cadhain has a style to match. The narrative mostly lingers in an uncomfortable and uncertain present, and even when snatches of memory and reportage intrude, they’re undermined by partiality and prejudice.

It might surprise, then, that Ó Cadhain’s affection for this sort of place, and for the people that inhabit it, was profound. Graveyard Clay takes few pains to clarify its setting, but references to nearby Galway city, and to a war happening overground, confirm that the action, such as it is, is set in its author’s home place, and during World War II – or the “Emergency,” as that period was known in Ireland. Ó Cadhain was born in 1906 in a Gaeltacht, or Irish-speaking district, in Connemara, County Galway. When Cré na Cille appeared, Connemara remained an impoverished region; culturally, it was out of step with the new, modernizing Irish state. Nonetheless, Ó Cadhain explicitly credited his native soil for giving him the gab, “the spoken language, the natural earthy pungent speech.” This needs bearing well in mind when we encounter the petty querulousness of his characters.

At its core, Graveyard Clay is a mordant denunciation of the poverty, factionalism, jealousy, servility, and narrow-mindedness that collaborate to undermine places like Connemara. Ultimately, the novel apportions blame to political, cultural, and economic developments that impinge upon Ireland’s west, but that Connemarans are powerless to influence. In this vein, Graveyard Clay derives some of its most unsettling – and most humorous – energies from class pretension, and class conflict, which work to produce an exceptionally vacuous form of cultural cringe. A sycophantic, Anglophilic relict named Nóra Sheáinín designates herself “cultural relations officer of the graveyard,” and sets about establishing a kind of cadaverous Rotary Club. It is founded not on artistic principle, but on priggery: another character, a writer, is told that he won’t be admitted on account of his “Joycean” style and morals. This was the epithet used by An Gúm, the publishing wing of the Irish Department of Education, to justify its decision to decline publication of Cré na Cille. “They don’t know,” Ó Cadhain reflected at the time, that “it is the highest praise they could give a work.”

Unlike James Joyce, Ó Cadhain stayed in Ireland, and wrote in Irish. All the same, he maintained a potent ambivalence toward An Gúm and its ilk, those organs of authorized – not to say orthodox – Irish culture and language, invented by the nation in the first few decades after independence. Though a leading light of Irish literature, he was a cutting critic of the homogenization and bureaucratization of the Irish language. Considering its small size, Ireland’s linguistic diversity is remarkable: the various dialects and accents of Irish are sufficiently distinct as to complicate communication between speakers in, say, Kerry and Donegal – southern and northern counties, respectively, separated by only a couple of hundred miles. Ó Cadhain’s language was, in some ways, intensely parochial, establishing its world through Connemara Irish’s distinctive vocabulary. But in other respects, it undertook an ambitious kind of Celtic cosmopolitanism, incorporating influences from beyond Modern Irish – from Hebridean and Scots Gaelic, Old and Middle Irish, and even Breton, a continental cousin.

Ó Cadhain referred to himself, in a biographical note for Cré na Cille, as “an organiser of language and of revolution.” This was more than metaphor. He was a member of the Irish Republican Army, and of the faction within the republican movement that rebelled in dissatisfaction after the passing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in early 1922. Ó Cadhain’s side lost the Irish Civil War, but he remained a political subversive. During the Emergency, he was arrested under the anti-terrorist Offences Against the State Act, and interned at the Curragh Camp, in County Kildare. Ironically, his time at the Curragh – basically contemporaneous with the span covered by Graveyard Clay – proved intellectually enriching, and enormously productive. While at the camp – which some internees took to calling “the University of the Curragh” – Ó Cadhain learned French, Breton, Welsh, and Russian, and edited Barbed Wire, the prisoner paper.

Through his linguistic and literary studies, Ó Cadhain engaged with European modernity, and later, with Graveyard Clay, he’d stake a claim within that modernity for Irish-language fiction. For literary touchstones, he cited Stendahl, Franz Kafka, and especially Maxim Gorky, the last of whom had been exiled to Italy after the Russian Revolution of 1905, and whom Ó Cadhain had first read, in French translation, in 1939. He would later claim to have had a copy of Gorky’s “A Harvest Day with the Don Cossacks” in his pocket when he was arrested. Another Russian writer may have had an even more immediate impact: in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s short story “Bobok” (1873), Ivan Ivanych eavesdrops on squabbling corpses in a cemetery. One of the bodies observes, in a manner felicitous to Graveyard Clay, that in a graveyard, a “body comes to life” once more, and “the residue of life is concentrated, but only in the consciousness….[It’s] as if life continues by inertia.”

As the nascent Irish nation established a conservative, and to a great degree theocratic, cultural identity for itself, Cré na Cille took stubborn exception. It not only took its cue from the cutting edge in European literature; it did so without relinquishing the Irish language, in all its specificity, idiosyncrasy, and indeed richness. Graveyard Clay has to be appraised in terms of this weird and transformative shuttling – between localism and cosmopolitanism, preservationism and iconoclasm. To read it in 2017 as a kind of dusty relic would be to seriously misunderstand its author’s spirit. In his treatment of language, no less than in his treatment of narrative, Ó Cadhain composed a work that was simultaneously insular in the extreme and boldly avant-garde.

Graveyard Clay is an unforgettably disconcerting work. It offers none of the consolations that we compulsively draw from – or project upon – dying, death, and the dead. Some of its preoccupations are vigorously, precisely situated in time and place, and anyone interested in a complex and contrarian view of Irishness at midcentury should read it. But Ó Cadhain’s strident refusal to romanticize the end of life recommends Graveyard Clay to all of us who tend to choose comforting idealizations over noisome realities. Death is basically indecent, and undignified, and the dead are no more deserving of indulgence or admiration than the living. Maybe the afterlife, if it exists, is a retrograde mess, and to inhabit it is to feel not spiritual transcendence, but a keen taedium moriae. These are unpleasant notions, but in their unamiableness they transmit strange, and ethically salubrious, truths. Graveyard Clay won’t redeem the dead – let alone the living – but it will give the buried back their mouths, and compel the rest of us to listen.

Killian Quigley is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Sydney Environment Institute, at the University of Sydney, New South Wales. He holds a PhD in English from Vanderbilt University. He is writing a book called Seascape and the Submarine: Aesthetics and the Eighteenth-Century Ocean, and co-editing a collection of essays entitled Senses of the Submarine. His writings are available in Eighteenth-Century Life, on the institute’s blog, and elsewhere. He is on Twitter at @killian_quigley.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig