by by Margaret Kolb

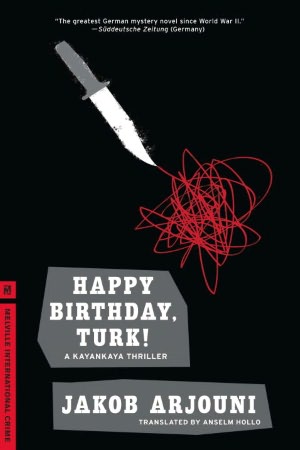

Published by Melville House, 2011 | 176 pages

Jakob Arjouni has been hailed – mainly in Germany – as the successor to American crime fiction masters Dashiell Hammett (The Maltese Falcon and The Thin Man) and Raymond Chandler (The Big Sleep and The Long Goodbye) since the release of his first novel, Happy Birthday, Turk! in 1987. Arjouni picks up the tradition of “hardboiled” private eye crime fiction Hammett and Chandler made popular in the 1920s and1930s, respectively, creating a dark, seedy world and an unorthodox private detective whose morals and actions may be as suspect as the criminals he pursues for money.

As with the other three novels that make up Arjouni’s “Kayankaya Thrillers” (all four recently translated from the German and republished by Melville House), Happy Birthday, Turk! centers on private investigator Kemel Kayankaya. Of Turkish heritage, Kayankaya was raised by a German couple after the death of his parents – his mother died in childbirth and his father, a garbage collector, was struck in traffic. A “Turk” who doesn’t speak Turkish, and a German who looks like a Turk, Kayankaya is a liminal character, trapped between worlds and within situations of exceeding instability. Debauched, hard-drinking, and self-loathing, Kayankaya is as oddly endearing as the genre dictates he should be.

The story of Happy Birthday, Turk! revolves around the stabbing death of Ahmed Hamul, a Turkish laborer, on the steps of his “junkie prostitute” girlfriend’s apartment building. The case is brought to Kayankaya by Ahmed’s wife after the police prove themselves unwilling, or unable, to conclude their investigation. In pursuit of the killer, Kayankaya dives into the seedy world of Frankfurt’s red-light district, overindulging in Scotch and caffeine, brawling, mouthing off indiscriminately, making enemies on both sides of the law, all the while slowly gathering together pieces of the puzzle.

Kayankaya’s Frankfurt is a raw, unemotional place devoid of social graces and table manners. In Arjouni’s portrayal it is coated in a genre-familiar, though not unwelcome, ugliness and grime:

“The neighbouring tabletops were filled up with plates of sauerkraut, bratwurst, and schnitzels. In the muggy air, jaws were tearing into breaded meat, lips smacking, vocal chords groaning and interspersing those noises with occasional speech. Tongues emerged to lick greasy chops. I had to burp and a slightly sour-tasting crumb of Sachertorte landed on my tongue.”The stark realism of these frank, red-eyed observations pepper the novel, firmly aligning it with the mandates of its rigorous, demanding genre.

Just as the setting of Frankfurt saves the novel’s tropes from becoming clichés, so too does Kayankaya’s ethnicity. Indeed, Arjouni leverages much of the novel upon it. Kayankaya cannot pose a question to anyone without first having to deflect casually racist greetings: “Mustafa,” “Aladdin,” and “Sheik.” As much as Kayankaya pariahtizes himself with sarcasm and belligerence, he still ends up a sympathetic antihero.

The wonderfully blunt, clenched-fisted descriptions of people and place almost compensate for dialogue which appears to have suffered a bit in translation. There is a disconnect between the fluency and style in which the novel’s scenes are set and the way some of the dialogue sags at times under a hackneyed dime novel detective idiom.

“When was he here?” “In the afternoon.” “What time exactly?” “Why is that so important, you dumb sleuth?” “It just is.”The plot itself is intricate and delicately rendered, and the conspiracies that unfold around the murder illuminates Arjouni’s rage at how those in power exploit and oppress Frankfurt‘s weaker subclasses – in this case, Turkish Germans.

The novel’s dénouement comes abruptly and perhaps a bit too quickly, and is explained away too easily on top of that. The novel even hedges a bit on its moral ambiguity at the end, a surprise considering that the precedent had been set years before by Greene, Chandler, etc. Was Arjouni in a rush to finish? Still, it is with no small astonishment that, over the course of Happy Birthday, Turk!, we come to know Kayankaya to be far more compassionate and authentic than than the novel itself had seemed to suggest he would be.

SD Allison was born in Nebraska. He is the descendant of farmers, teachers, and men with bad lungs. He is the father of a little boy with autism. His first novel, Beneath the Plastic, was published in 2006. He is currently a senior copy writer for a marketing/ad agency.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig