by by Margaret Kolb

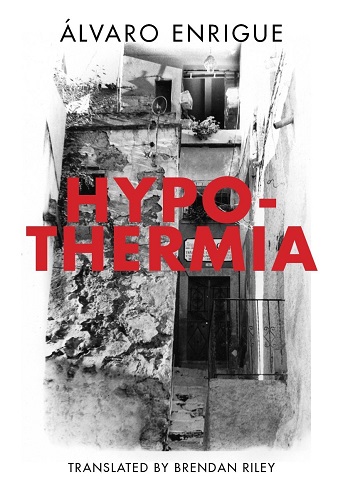

Published by Dalkey Archive Press, 2013 | 198 pages

The origin of the word gringo is a nebulous one. There is the popular but spurious story that when U.S. American soldiers were in Mexico in the mid-nineteenth century (presumably during the Mexican American War), Mexicans would be subjected to the grating spectacle of unaccountably chipper soldiers singing and marching to the tune of “Green Grow the Lilacs,” of which the Mexicans, knowing only a modicum of English and regarding the grs-grs of the Americans as barbarous, misapprehended the lyrics as “gringo the lilacs.” But the likelier truth is that the etymology of gringo precedes North American militarism and dates back to an early modern corruption of the word griego (“Greek”) in Castilian, used then in the same idiomatic sense that it was once said in English, “It’s all greek to me,” i.e. unintelligible, unfamiliar, foreign. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar offers the more famous instance of an idiomatic sentiment that dates back to an old Latin saying: Graecum est; non legitur (“It’s Greek; it cannot be read”). In today’s parlance, and particularly in the mind of a Spanish-speaking immigrant beginning to live in the United States, what’s “greek” and cannot be read would translate to: “what’s gringo is what I don’t understand.”

In Álvaro Enrigue’s collection of short stories, Hypothermia, no word seems more salient than gringo. By my count it emerges at least thirty times across a span of twenty stories, in each instance connoting something of a double reality: the literalist reality of the gringo and the figurative reality of the non-gringo resisting gringofication. In Enrigue’s world, el gringismo begins and ends with estrangement. Most of the characters in Hypothermia (at least when they’re presented in the first person) are Mexican males living and working in the United States in the invariable guise of a writer-professor-husband-father struggling with, reinterpreting, or otherwise giving into gringo life. That Enrigue himself is a Mexican author living in the United States brings some ludic level of self-referentiality to the depictions. (For example, the narrator of one story notes that a taxi driver driving him through the streets of Lima, Peru, pronounced his name “noticeably weighting the first accented vowel then letting the rest fall into silence with princely disdain,” a description in which “Álvaro” would naturally fit.)

In “Diary of a Quiet Day,” contained in the first batch of stories collected under the deceptively innocuous title “Scenes from Family Life,” a man watches a baseball game (in many ways the ultimate gringo sport) and ruminates on how “baseball is an Odyssean sport: the batter has to circle round the archipelago of the bases to get back home.” Left alone for a day at a large vacation home on the Outer Banks of North Carolina (his wife and son are away on a trip with the inlaws), the man notices a sign above a doorway that states that the house he is staying in is named “Ithaca.” The irony, of course, is that while he was prefiguring himself as an Odysseus stranded on American Ogygia with the Calypso charms of baseball and all things gringo (he helps himself to copious Diet Cokes, “bags of Tostitos as big as TV sets,” and “a box of Froot Loops the size of a briefcase”) he turns out to be a mixture of Telemachus and Penelope, helplessly awaiting the delayed return of his family. In a more general sense, however, he still is a chilango Odysseus, one of many Mexicans and Latin Americans living out a form of capitalist exile in the United States. In another sense, however, he is also already a gringo who, like other characters in Hypothermia, listlessly has affairs, goes to therapy, and watches baseball (in the USA, as another fellow “exile” puts it, soccer is reduced to a mere diversion for children). Gringo, after all, is just another way of saying griego (again, “Greek”), a pseudo-Odysseus in nostalgia for the epic gesture or, lacking that, another giant box of Froot Loops. “That’s why, sooner or later, all of us gringos end up going to therapy. In a world like this one, the only way to get someone to listen to you is by paying them to do it.”

Other exiles make appearances. In “Heavy Weather,” a professor of Latin American literature (very likely the same narrator stuck in the North Carolinian Ithaca of the previous story) experiences a monstrous tornado while teaching a class on Rubén Darío’s Odyssean travels abroad. At another point he speculates on the life of Mexican author Martín Luis Guzmán, whose “periods of exile, like those of Quevedo, were authentic and obligatory.” Guzmán’s career brings to mind not only Odysseus, but also Julius Caesar and V.S. Naipaul, all who had been in some shape or form strangers in strange lands. The professor teaches in Washington D.C., capital of gringolandia, and endures an estrangement obtusely metaphorized by the tornado, a natural disaster that punctuates and overshadows his own estranged life. Yet again separated from his family, he walks through streets emptied by the tornado to the university sports complex, now serving as a provisional haven from the tornado. An acquiescent orderliness seems to typify gringo life even at the most trying moments: “Gringos are an obedient sort of people: in full compliance with the authorities they were now organized into assigned groups and distributed throughout the gigantic subterranean sports complex...”

In “Saint Bartholomew” (part of the third collection of stories subtitled “Filth”), another Mexican transplant, also living in D.C. and working at the World Bank, carries a story-length conversation with his mistress over cellphone, a technology that “made him tense because – he thought – it conjures up a frustrating and illusory sense of nearness; information is accelerated but nothing is communicated, at least not in the strict sense of the world. No matter how much you want it to, an empty, disembodied voice does not represent an act of communion.” Cellphones (in a time antedating the emergence of the smartphone) distort proximity in the same sense that becoming gringo distorts one’s intelligibility to others; to be a gringo is to be misunderstood, paradoxically, by becoming too literal. In a foreign land, alienation excites an incoherent preponderance on details.

The narrator of another (to my mind the best) story in Hypothermia, “On the Death of the Author,” plans to write a story on the life of Ishi, the last surviving member of the Yahi tribe who eventually lived out his life as an animate museum piece at UC Berkeley. The narrator struggles to overcome the inescapable literalness of Ishi's history, its too evident resonance as a tale restricted to the gratuitous plainness of its events. As the narrator informs us, Ishi falls into the habit of saving the money he earned from his wages as a maintenance worker at the university (they could find no other way of sustaining his living except by “hiring” him) and periodically would open the safe and “set his boxes of dollars on a table and spend the afternoon looking at them, without ever saying anything or taking the coins out. As if they were something else.” Ishi, suffering from a species of capitalist schizophrenia, stores his money and, instead of spending it, ritualistically gazes at it; the author-narrator attempting to write the story of Ishi, likewise stores up details of Ishi’s life and obsessively gazes at them, “as if they were something else.” But, in a world of literal overkill, the parts never add up to anything other than the single-track machine they constitute; money carries only one, insufferably mindless, meaning. Forced into a temporal (rather than a spatial) exile, Ishi becomes a gringo, that is, he adopts the strange customs of a different culture, and becomes estranged from his own--of which he is, unironically, the last and only member.

Enrigue thus redefines what it means to be a gringo. Neither white nor brown, U.S. American or Native American, the gringo is the cultural manifestation of estranging processes whose assortment of parts adds up to nothing but themselves, parts that interlock but never cohere. “Gringos? We’re African Americans, Mexican Americans, Native Americans, German Americans, Irish Americans…We’re neither an empire, nor a republic, nor a monarchy. We’re nothing...We’re whatever slipped through the cracks of history: pure ambition without any ulterior commitments...We’re gringos and we urgently need some national therapy.” In the collection’s first story, “Dumbo’s Feather,” which serves as a prelude to Hypothermia as a whole, the narrator (yet another Mexican author, a failed Odysseus, who seems to serve as the spirit of malaise and mediocrity that infuses so many of the characters) promises to write “stories about people who aren’t working through difficult questions or pathetic feelings; minor characters – people who’ve never visited Paris, people nobody cares about. Gringos, for example. Normal, everyday gringos like the tourists you see on the street in their Bermuda shorts.”

Developing a chain of associations that presents the USA as a land of metaphysical refrigeration (or as Henry Miller had placed it, an “air-conditioned nightmare”), Enrigue constructs a dual image for the expatriate writer living in twenty-first century America: a white backdrop on a plasma screen, and one's own face, now the face of another, emerging from this whiteness. In the appropriately titled "White," another Mexican-turned-gringo watches the videotape recording of a snowy day spent with his daughters, "a pure white color" appearing on the screen, until "at last his own face appeared, talking about the snow and the cold." Even if "he couldn't stop thinking about his Odyssey, stuck fast in the pristine snow," the nostalgia for warmth motivates a contrapuntal image of a phantasmal fulgent Mexico shifting in the distance. The literal, we learn, counters but does not completely obliterate the figurative. Though Mexico, specifically Mexico City, as a narrative site is largely absent in Hypothermia (it only appears in the final story, as a sort of libidinal recovery), it remains present in this absence--it represents a robust metropolitan figurality that traverses and overlaps with the snowfields of the literal, an ardor for native lands that sets the homogenous suburbs of east coast America into stark relief. As Heriberto Yépez has written in The Empire of Neomemory, “For the North American, the Mexican is the pseudo-maternal. [...] American solitude has to do with the separation from Mexico, with the co-bodies always absent, relative to each other, one with respect to both. The United States and Mexico are doubles.”

More to the point, to turn gringo is to become, culturally and metaphysically speaking, “white,” to turn cold in a consumptive estranging realism, to lose the so-called “warmth” of the indigenous co-body of the south. “After reaching a certain size, a secret generates a zone of silence around the one who carries it. Like a refrigerator, it has its own microclimate that people can poke their heads into but where no one else can remain… The question was: had his deficiencies led him to become a refrigerator or were they one more eventuality in his destiny as a refrigerator?” To become a gringo is to grow into a refrigerated state of bland literalities that never mesh into something else. In a manner of words, to become a gringo is to (figuratively) die of hypothermia from an excess of (literal) air conditioning.

Jose-Luis Moctezuma is a current doctoral student at the University of Chicago. His studies focus on technologies of the image in poetry, cinema, and literature. His work has been/will be published by Berkeley Poetry Review, PALABRA, and Cerise Press.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig