by Zane Koss

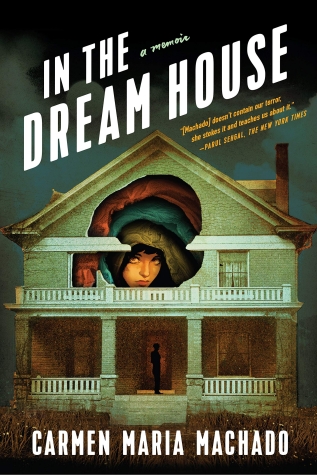

Published by Graywolf Press, 2019 | 272 pages

Everything tells a story.

Societies tell stories about power and freedom, who deserves them, and why. Relationships tell stories, especially as they end: who is the hero, who is the victim, who is the villain? People tell stories, too. About themselves, about others, about the way the world works. They do this to make things make sense. To justify their actions. To get through the day.

In these narratives, people learn and grow, win and lose, hurt each other, reconcile.

They dream. They exist.

But what happens when you’re left out of the story, even your own story, altogether? Maybe you feel somehow wrong or impossible, or invisible, even to yourself. Maybe you start to wonder whether you do, in fact, exist.

The prologue of Carmen Maria Machado's memoir, In the Dream House, defines the concept of archival silence: “sometimes stories are destroyed, and sometimes they are never uttered in the first place; either way something very large is irrevocably missing from our collective histories.” Queerness itself has been left out of the narrative for much of history, and even now, as Machado notes, abuse in queer relationships is still a largely untold story. The CDC acknowledged, in its 2010 survey of intimate partner violence, that “Little is known about the national prevalence of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence” amongst LGBTQ couples. Ten years later, statistical, academic, and societal factors continue to complicate the understanding of both the prevalence and the nature of abuse in same-sex relationships, particularly those between women. Issues affecting the data include small sample sizes in many relevant research studies; reluctance amongst lesbians and bisexual women to report violence perpetrated by members of their own community; and even heteronormative language used by staff at domestic violence shelters, who may assume all abusers are men.

Machado reckons with this archival silence –– the unknown statistics, the sparse and spotty data, the unreported incidents, the help that comes bundled with erasure –– by telling her own story. “Our culture does not have an investment in helping queer folks understand what their experiences mean,” she writes. Here, she tries to make this meaning anyway.

In the Dream House tracks Machado’s relationship with her unnamed ex. The two women meet in Iowa City, where Machado is studying for her MFA. They begin a turbulent relationship that passes through many phases –– polyamorous, monogamous, long-distance, troubling, downright scary –– but that first night, Machado is smitten: “she touches your arm and looks directly at you and you feel like a child buying something with her own money for the first time.” They have sex and take road trips. They write and go to parties and plan a version of the future together. They fight. A lot. Machado cries, a lot. Throughout, Machado does a brilliant job conveying all the ways in which the “woman in the Dream House” was alluring to her, and, despite the emotional and –– at times –– physical abuse, her very real grief when their relationship ended. Even after all that awfulness, there’s the inevitable nostalgia: “You occasionally find yourself idly thinking about how it could have gone right.” And there’s the terrible sense of loss, even amidst all the ugliness: “Afterward, I would mourn her as if she’d died, because something had: something we had created together.”

The story is in turns heartbreaking, sensual, and disturbing. But perhaps most significant of all is the way Machado chooses to tell it. Rather than settling on one form, point of view, or genre, Machado writes In the Dream House in a series of short, dense, and gleaming chapters that play with different genres and literary tropes, or reference different mediums. With titles like Dream House as Picaresque, Dream House as Bildungsroman, Dream House as Road Trip to Everywhere, and Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure, each explores an aspect of Machado’s relationship with the unnamed woman or the circumstances that led to it. Each tries to make sense of the experience in a new way. Because most of the memoir is written in second person, with the narrator addressing her former self: you, you, you, the book feels both intimate and vaguely instructional, as though––through these varied approaches to storytelling––the narrative is trying to do the work of meaning-making for queer people that the culture at large, in Machado’s view, has long failed to do.

In one particularly compelling section, Machado talks about having no example for what’s normal when dating a woman, a truth that contributed to the difficulty of recognizing and naming what was happening to her. “You trust her,” Machado writes of her ex, “and you have no context for anything else.” Machado touches again on this lack of context in a passage where she describes realizing, many years later, that she had a crush on a classmate when she was young. “I didn’t know what it meant to want to kiss another woman,” she writes, recalling how she would stare at her classmate’s freckles. Years later, she figured it all out… “But then, I didn’t know what it meant to be afraid of another woman. Do you see now? Do you understand?”

Machado is an accomplished horror writer whose debut, Her Body and Other Parties, won the Shirley Jackson Award, was a finalist for the National Book Award, and was widely credited with blending horror with science fiction, dark comedy, and a sensibility both literary and grotesque. In the Dream House is neither fiction nor horror, but here Machado still manages to effectively communicate the psychological trauma and the utter creepiness of feeling “trained to be found” by an abusive partner who seems “trained to find you.” By the memoir’s end, any reader can understand what it’s like to be afraid of a woman.

In this way, one of Machado's achievements with In the Dream House is the vividness with which she fleshes out the trauma that remains in the wake of an abusive relationship. Yet, despite the disturbing reality at its core, the book also feels deeply hopeful. This may be because the memoir’s structure –– the use of so many different narrative forms –– is itself a hopeful reality. In a patchwork of traditions and genres, Machado has begun the work of constructing this same context that she once lacked. Interestingly, Machado addresses this choice of narrative structure within the text, positioning it not as an aspirational act, but as something of a last resort: “I broke the stories down because I was breaking down and I didn’t know what else to do.” But from an audience perspective, each new genre Machado explores –– Fantasy, Exercise in Style, Comedy of Errors, Cautionary Tale –– also feels like a small act of resilience: like the pulling up of a chair to a new literary table. With each piece of this story, Machado claims a bit of space for women who love women, in a literary canon that has not always made space for this love. It’s a response to the archival silence. A direct and noisy one, at that.

With In the Dream House, Machado offers a model for creating a new language out of the messy bric-a-brac of the everyday. Here Machado is a victim, yes, but she also becomes namer, author, narrator, and protagonist––and not just in one story or genre, but many. By the end of the book, Machado reclaims her own first person: “Many years later, I wrote part of this book in a barn on the property of the late Edna St. Vincent Millay.” Not coincidentally, it’s the act of writing that becomes transformational. Machado is subject now, rather than object. She is no longer a “you,” but once again an “I.” It is through writing, in the end, that Machado grasps her way toward a reimagining of what it means to be queer, resilient. To become the protagonist in a tapestry of stories, and to make them all one’s own.

Erin Becker is a freelance writer, editor, and translator. She is an MFA candidate at Vermont College of Fine Arts and a graduate of the English and Creative Writing program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig