by Angela Moran

Published by Duke University Press , 2013 | 304 pages

The history of Western music has often been written as a history of composition, and the stories told have tended to focus on the sublimation of musical elements once considered inadmissible—or “dissonant”—into new norms. If Richard Wagner’s “Tristan chord” and Arnold Schoenberg’s “emancipation of dissonance” set the musical language of Romanticism bursting at the seams, then, by the eve of the First World War, Luigi Russolo’s L’arte dei Rumori (The Art of Noises) pushed it squarely over the edge. Engaged by the mechanical sounds of early twentieth-century Europe’s growing urbanity, Russolo’s manifesto called for composers to enrich their palette by “[conquering] the infinite variety of noise-sounds.” Forty years later John Cage would unveil his infamous “silent” piece, 4’33”, “composed” solely of incidental sounds and noises, lacking any compositional intention whatsoever.

During the second half of the twentieth century, this penchant for “pure” sound filtered through the circuits of a new generation of musicians who then concretized it into a musical genre: Noise. The Velvet Underground, dually influenced by Lou Reed’s mordant lyrics and John Cale’s interests in minimalism and drone (Cale had studied and performed with John Cage and La Monte Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music), are often credited with pioneering Noise’s emergence within the realm of so-called “popular” music. By 1975, Reed, the Velvet’s front man, had produced Metal Machine Music, what many now consider to be the first unadulterated essay in the new Noise genre, while, across the Atlantic, groups like Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle were responding to the negative effects of England’s industrialization by pioneering a style that would be termed “industrial.”

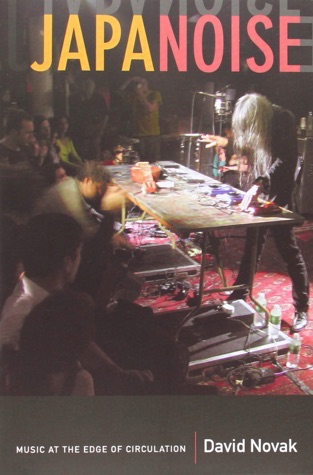

David Novak’s Japanoise is an exploration of Noise’s singularly Japanese manifestation, which first surfaced in the 1980s. His text investigates the scene’s aesthetics and practices, from audio mastering techniques that emphasized what Novak terms “deadness” (chapter 1, “Scenes of Liveness and Deadness”), to the cassette culture that developed around the scene in the 1980s—which, against all odds, persists to this day (chapter 7, “The Future of Cassette Culture”). Furthermore, Novak contextualizes these elements within larger historical and theoretical frameworks, shedding light on a wide range of topics, including Japan’s postwar history, globalization, and technology.

Chapter 3, “Listening to Noise in Kansai,” explores how Noise’s emergence in Japan was shaped by a series of postwar economic and social reform movements that emphasized the consumption of new communication technologies and foreign culture in an effort to enact what Novak describes as a “geopolitical realignment” with the United States. As Japan began to look abroad for new cultural products, foreign recordings were privileged over domestic live performances of local music. Attentive listening in the jazu-kissa—a postwar café where small, self-selected crowds of auditors honed virtuosic listening skills—became a hallmark of the emergent Japanese cosmopolitanism. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, these marginal spaces had been devoted to new, experimental music, but by the 1980s, their focus shifted in a more conservative and reactionary direction. The radical-experimental lacuna left by the evolution of the jazu-kissaten was filled by new “free spaces”—such as Kyoto’s Drugstore—in which new sonic terrains, including those of Japanoise, would be explored.

A typical noise performance setup is comprised of common, commercially available effects pedals—“electronic goods” produced by (often Japanese) companies like Roland—connected together in such a way that they feed back into each other. As the flow of signals becomes increasingly complex, performer control is diminished, foregrounding the semi-autonomy of the system. As Novak writes, “noisicians are deeply involved in the search for a sound-producing environment that is neither determined by a distinct composer nor fully controlled by the performer.” And yet, the noise musician’s attitude toward electronics can be described as much as one of denigration as supplication. Indeed, Novak argues that Japanoise arose partially as a critique of the nation’s open embrace of technology. Regardless, the end result is disruption. The theatricality of this disruption’s execution has run the gamut from the destruction of stage equipment to the destruction of an entire venue, as Yamatsuka Eye of Hanatarashi and Boredoms infamously did with a backhoe bulldozer in 1985.

Novak’s study of Noise in its specific Japanese incarnation succeeds by grounding the ontological complexities of noise in ethnographic research. But even this subsection of the Noise genre presents challenges for traditional ethnography, and Novak notes that the Japanoise scene “does not settle in a distinct place or group of people,” making impossible the specification of any single “ethnographic terrain.” Novak employs the concept of feedback to emphasize how circulation functions as a culture-making process: “Listening from afar,” he writes, “North Americans imagined the Japanese Noise scene as a cohesive, politically transgressive, and locally resistant community—in other words, a version of their own ideal musical world in an unknown cultural space.” Somewhat humorously, after their influence spread abroad, Japanoise artists found themselves validated at home by a process Novak describes as “reverse importation,” culminating in a series of bizarre appearances on Japanese national television in the mid-1990s.

As Hiroshige Jojo of Hijokaidan remarks in Japanoise, Noise “includes many things… but almost no one can know and understand Noise. That’s a very good and important thing. Because—there’s hardly anything we don’t know any more, is there? But there are still mysterious things, right? … Noise must be this kind of mysterious thing.” Just as Noise makes possible the experience of sound as sound, of the mathematical and physical vibrations of matter, likewise does it turn the focus of its listeners inward, where one is confronted with hearing in its most direct and primitive sense. Through the delicacy and care with which he attends to noise, to its makers and its auditors, Novak shows us how to listen anew and to hear previously unreckoned constellations of sounds, feeding back through the circuitry of the global underground.

Farley Miller is a Ph.D. candidate in musicology at McGill University, where his research focuses on technology and popular music.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig