by by Margaret Kolb

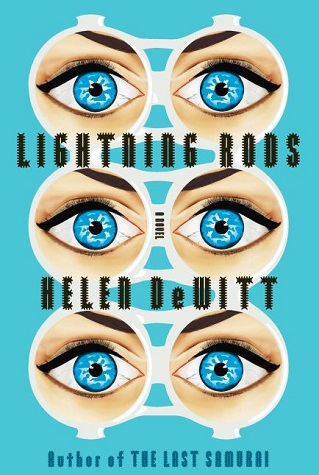

Published by New Directions, 2011 | 275 pages

If the recent Walter Isaacson biography of the late Steve Jobs has a companion volume in the world of fiction, Helen DeWitt’s new novel Lightning Rods may be it. Lightning Rods is, ultimately, an account of business genius: specifically, of the bold, inventive product-vision that so transformed American culture in the first decade of the twenty-first century. The key events of the novel take place at the turn of the millennium, but the novel is narrated from the present by a nameless observer. As the narrator tracks a remarkable sequence of epiphanies experienced by protagonist “Joe,” we learn the history of human resources firm Lightning Rods, Inc., which markets and places “bifunctional” female staff willing to perform regular secretarial and administrative duties as well as earn substantial additional income by participating in a kind of anonymous, computer-facilitated sexual roulette in their workplaces. The system works like this: a few times a day, a female “lightning rod” will be paired anonymously with one of the male staff members by a message that appears on the computer screens of both parties. If the male employee elects to pursue the lightning rod’s services, which is entirely voluntary, both participants separately make their way to specially modified disabled stalls in the men’s and women’s bathrooms. The back half of the female participant then passes backward through a hole in the wall between the gendered bathrooms on a “transporter,” and the male staff member, equipped in the stall with condoms and lubricant, can enjoy a few moments of no-strings-attached ventro-dorsal intercourse on the company dime in the name of collective productivity. Designed to help corporations avoid disruptive sexual harassment lawsuits, Lightning Rods, Inc. is wildly successful.

Lightning Rods the work of fiction is as well. Perhaps to a greater degree than any fiction set in a corporate space since Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine (1986), the level of pure novelty attending the fictional world of Lightning Rods is very high. Just watching DeWitt’s third-person narrator explicate—and, through no small labor, sell—the philosophical meaning of the trials and tribulations of a former door-to-door vacuum-cleaner salesman’s innovative business idea is hypnotically entertaining. The work is so successful, in fact, that it is very easy to get distracted from the important sociopolitical argument it is making.

Much of the force of this sociopolitical argument is located in the work’s portrayal of the, ahem, “innovation,” Lightning Rods Inc. introduces as being beneficial, at least in economic terms, for both its male and female participants. The business idea works, DeWitt implies, precisely because it offers not only men the ability to clear their minds, but also women the opportunity to get ahead financially by embracing the compromised positions they presumably would have found themselves in anyway. One ambitious lightning rod, for example, uses the time her back end is hanging through a wall to read Proust, which, according to her, is “no different from reading a book while you have a massage, or a jacuzzi.” DeWitt writes, by “the time she reached the end of A la recherche du temps perdu she’d have earned $100,000 just out of time spent reading Proust,” learning French in the process. This enterprising woman later becomes a Supreme Court justice.

It is difficult not to chuckle, grimly, at DeWitt’s expert negotiation of these and other ironies of this bizarre, almost-plausible, alternative universe. But DeWitt’s real world argument, outside the safely partitioned frame of the satire, is a serious one, and it actually has less to do with sexual harassment than it does with wage inequality. Presumably DeWitt has read her Michel Foucault, since Lightning Rods is essentially a dramatization of The History of Sexuality. Its point, if you will, seems to be that our collective obsession with sexual misconduct in the workplace masks more fundamental inequalities and power imbalances. In this light we can read Lightning Rods as a thought experiment in which sexual harassment is simply removed from the equation. Consider: in the world of Lightning Rods, subsequent to the introduction of no-strings-attached intercourse to the workplace, women immediately achieve wage equality, and through it great leverage to pursue their own goals outside work. DeWitt’s point ultimately appears to be that the widespread acceptance of institutionalized paternalist hierarchies is a social crime, but one that also disguises more basic, more latent, and more damaging social inequalities. As a cultural artifact circa 2011, Lightning Rods thus constitutes a deconstructive particle with a highly reactive valence. Forget about the obvious power exploitation of sexual harassment for ten seconds, DeWitt announces, and you will see the degree to which corporations and other institutions are still fundamentally sexist and racist.

Like DeWitt’s first novel The Last Samurai (2000), which was acclaimed for its formal originality, the literary effect of Lightning Rods is as much about the means of its own narration as it is the provocative business idea at the novel’s core. As noted above, there is a rift in time between what we might call the narrative present of the novel and the fully-informed moment of the novel’s telling—a temporal distance of four years between the action during which the novel takes place (1999-2003) and the now—and DeWitt closes this rift only gradually and by degrees. The immediate, local effect of this is one of heightened suspense. The reader is forced to persistently wonder whether Lightning Rods, Inc. might explode in the faces of its designer and participants, since the legal dimensions of the company are left conspicuously unresolved until late in the book. When we finally reach the moment of the story’s telling – the now – Lightning Rods Inc. has come to serve countless corporations as well as the federal government. As Lightning Rods, Inc.’s fate becomes known, the novel’s temporal suspension is shown to be an important vehicle of its argument. What the reader had expected to turn out to be a blip in history, a transgressive but ultimately shortsighted innovation that explodes in its creator’s face, turns out to have become a cultural institution. By extension, the narrator, who had seemed to be a third-person satirist coextensive with DeWitt herself—a mere thought experimenter—becomes, the reader realizes with no little discomfort, a kind of emissary of an alternate universe. In its masterful, surprising execution of this plot of delayed revelation, Lightning Rods thus transforms itself from a speculative cautionary tale into a chronicle of an alternate reality, and one so viable its ability to speak to our own is uncanny.

For its ability to potentially offer a cultural intervention on this level, Lightning Rods bears a resemblance to the fiction of British writer Kazuo Ishiguro, especially the chilling 2005 novel Never Let Me Go, where a system of human cloning and organ harvesting has been established, and accepted, in an alternate history of late-twentieth-century Britain. Like Lightning Rods, what makes Never Let Me Go so compelling is its intricacy; it purchases its realism by describing an entire culture of organ donation and harvesting. And like DeWitt’s novel, its argument is not about the world it describes, but our own, where—though organ harvesting may be illegal—it still occurs, and other atrocious social injustices are accepted and often unremarked. Such novels press on generic boundaries, and bear, in their epistemological assumptions, a strong resemblance to science fiction. They operate according to a logic that says, satirically, obviously things are not this way, but in another sense they very much are.

At the end of the day, DeWitt’s tongue remains more or less tucked in her cheek. Lightning Rods remains a predominantly satirical work. Beyond placing condoms in the bathroom stalls, DeWitt does not address potential complications such as accidental pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, or, to any depth, the long-term psychological effects of participation in what is essentially sanctioned, anonymous prostitution. Hers is a book of jokes, and – especially through comic section titles like “Failure is Always the Best Way to Learn,” “There’s More to Life Than Money,” and, her final chapter, “That’s All Folks” – DeWitt calls frequent attention to Lightning Rods’ artifice. Unlike Ishiguro in Never Let Me Go, DeWitt is willing to eventually let us go; she doesn’t expect us to walk away from Lightning Rods quaking in our boots. And yet her novel ultimately bears on literature in the second decade of the twenty-first-century in a way that exceeds even the novel’s satirization of corporate culture. As noted above, Lightning Rods is, in the first place, a book about “genius,” and about how genius sells itself to consumers who, to cite the well-known marketing formula of the late Steve Jobs, don’t know what they want until it is shown to them. Yet isn’t the author of a satirical novel, whether its modest proposal is human cloning or sanctioned prostitution in the halls of corporate America, in a similar position? Like her protagonist Joe, Helen DeWitt must market and sell the possibility of Lightning Rods, Inc. to her reader; all of Joe’s brilliant innovations belong, at the end of the day, to DeWitt.

Near the end of the novel, DeWitt’s narrator describes one of Joe’s many ingenious efforts to streamline Lightning Rods, Inc. with the following statement: “Sometimes your own mind can actually be more of a mystery to you than the most enigmatic of strangers.” There is a metafictional quality to this maxim, and by extension to Lightning Rods as a whole; what a novelist produces, too, is not entirely in her control. It remains a mystery until it comes to life on the page. It is, in other words, an affair of genius. The most interesting byproduct of DeWitt’s novel may thus be its character as an implied reminder that, in an age where genius figures like Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg and other innovators of computer-age technologies and media increasingly capture the imagination (and dollars) of the American consumer, artistic genius, in the this case literary genius, can still sometimes get the upper hand.

Kevin C. Moore is a PhD candidate in English at UCLA. He works on nineteenth- and twentieth-century American literature, and he is currently completing a dissertation titled The Rise of Writer’s Block: Myths and Realities of American Literary Production. His essay “Parting at the Windmills: Malamud’s The Fixer as Historical Metafiction” is forthcoming in Arizona Quarterly. He lives in Santa Barbara, California.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig